Story highlights

Ninalee Craig appears in iconic photo "An American Girl in Italy"

She says the photo represents independence, not harassment

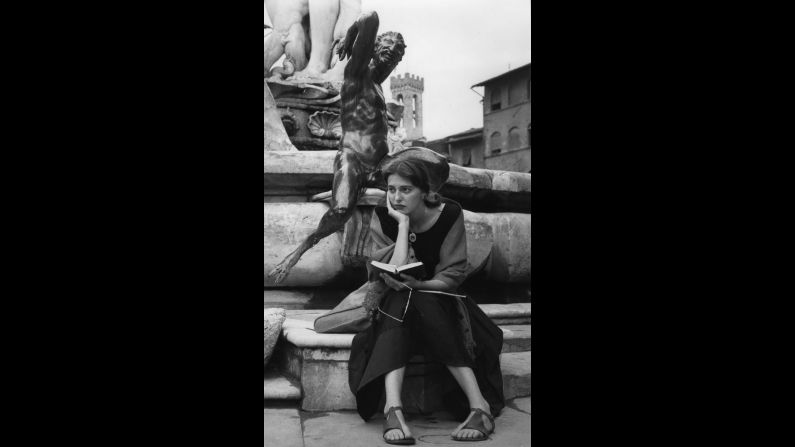

People tend to wonder if the iconic photo of Ninalee Craig was staged.

It’s the question she hears most often. To some, the scene in the black and white photo from another era is almost too perfect. Craig, 23 at the time, breezes past clusters of men on a sidewalk in Florence, Italy, head held high as if impervious to their ogling as she grasps her shawl and handbag.

Now 89, Craig insists the answer is no, still no. “It’s the real McCoy.”

The next most frequent question is one Craig has been trying to move past for as long as the photo has been in the public eye: Was she afraid? Was she upset that she could not walk down the street in peace?

Again, the answer is no. “I was thrilled. I was having the time of my life,” Craig says.

“I was Beatrice walking through the streets of Florence. I felt that at any moment I might be discovered by Dante himself.”

For all its controversy, photographer Ruth Orkin’s “An American Girl in Italy” has long been a fixture in women’s dorm rooms and homes, an instant conversation starter about feminism and street harassment long before the term came into use.

Craig and Orkin’s daughter Mary Engel, who represents the deceased American photographer’s estate, say the photo is more relevant now than ever for what it truly represents: independence, freedom and self-determination.

After all, that was the point of the photo to begin with.

Craig met Orkin in Florence in 1951, a time when it was unusual to find Americans in Europe, especially women traveling solo.

Craig had saved up money from a teaching job in New York. Taking her mother’s advice, she planned to travel Europe until the money ran out. She had visited France, Spain and England before settling in Florence to take art classes.

Orkin had just wrapped up a shoot in Israel for Life magazine. The two met at the American Express office, the place for sending letters and telegrams, making phone calls and exchanging money before the era of mass telecommunications.

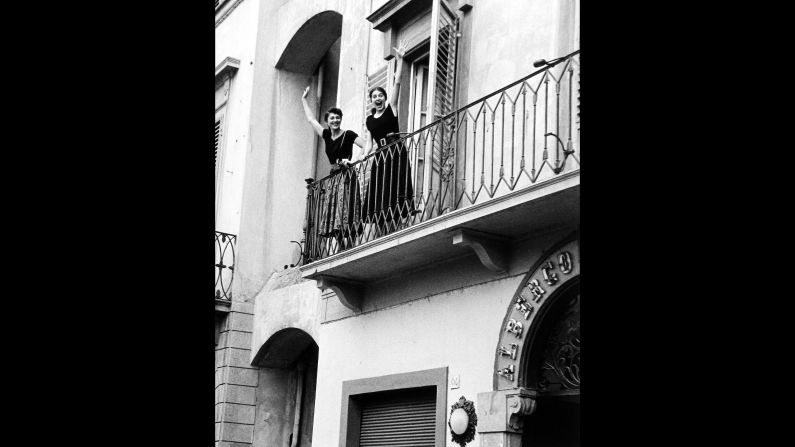

The women reveled in meeting each other, especially when they discovered they were staying in the same hotel for $1 a night (meals included). As they bonded over their shared passion for travel, Orkin proposed a photo shoot portraying their adventures.

“Ruth said, ‘Hey, you know what, I could probably make a bit of money if we horse around and show what it’s like to be a woman alone,’” Craig recalls.

The two hit the streets of Florence the next morning around 10 a.m. The shot of Craig passing by the men was one of the first Orkin snapped. She followed it up with another shot from a different angle before the two continued on to capture familiar scenes from Italy: cafes, statues, piazzas, cobblestone streets.

The shoot took about two hours and the pair went their separate ways, though not for long. As those rare Americans in Europe, they bumped into each other again in Paris and Venice and took more photos for Orkin’s series.

The photos ran in Cosmopolitan magazine in 1952 in a photo essay, “When You Travel Alone…”, offering tips on “money, men and morals to see you through a gay trip and a safe one.”

The article encourages readers to buy ship and train tickets ahead of time. It reminds them to bring their birth certificate and check in with the State Department.

The caption on the photo of Craig walking down the street reflects cultural mores of the era.

“Public admiration … shouldn’t fluster you. Ogling the ladies is a popular, harmless and flattering pastime you’ll run into in many foreign countries. The gentlemen are usually louder and more demonstrative than American men, but they mean no harm.”

It’s a far cry from what we tell women these days, but for its time the mere notion of encouraging women to travel alone was progressive. That’s what made the photos so special, Craig says. They offered a rare glimpse of two women – behind and in front of the camera – challenging the era’s gender roles and loving every minute of it.

“I look at it and I’m taken right back and it was wonderful,” she says. “I was an art student. I was carefree. I was 23 and the world was my oyster.”

For most of the 20th century, Craig was known by a nickname, Jinx Allen. Then, in the 1980s, the photo was featured in “Life” magazine and her identity was revealed.

In the interim she’d lived what she calls multiple lives, first as a countess in Italy through marrying an Italian, then as the wife of a Canadian steel company executive. After her second husband died she was drawn to Toronto’s emerging arts scene and found her home there. Forty years on, she jokingly calls herself “the Canadian girl” instead of the American.

She delights in talking about her six months in Europe and meeting Orkin, a kindred soul whose photos of her capture the spirit of the era – especially that iconic photo. The two eventually reunited in the United States and became lifelong friends, until Orkin’s death in 1985.

“She was an amazing woman,” Craig says of Orkin. “We had a grand time.”