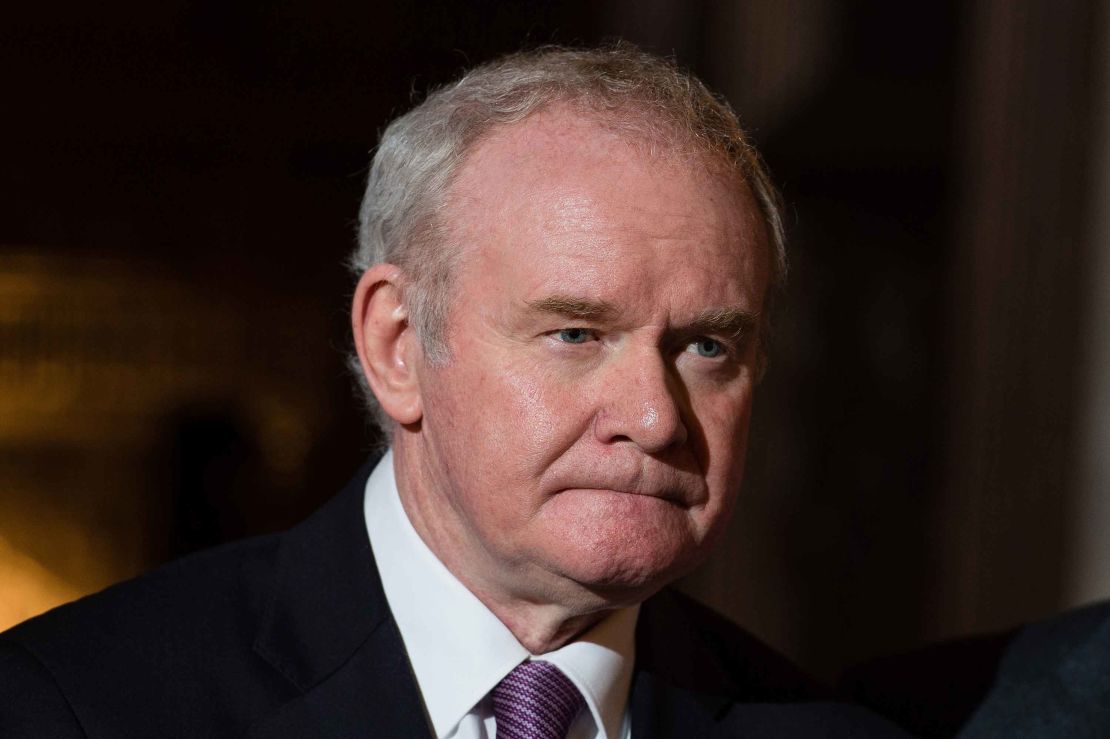

To his friends, Martin McGuinness was the Nelson Mandela of Northern Ireland; to his enemies, he was seen as a terrorist.

McGuinness, who has died aged 66, rose through the ranks of the IRA, from stone-throwing youth to feared fighter and, finally, after joining the peace process, to elder statesman of Northern Irish politics.

Through all the twists and turns of his life, he was never in any doubt about what he wanted: an end to British rule in Northern Ireland.

“I am an Irish republican,” he told me. “An Irish republican is someone who believes that the British government should have no part to play in the life of this island. We believe this island should be free.”

I first met McGuinness in the early 1990s. Years later, when he was serving as education minister in the province’s newly-minted power-sharing government, he invited me to film a documentary about him.

He was charming, affable, and always ready with a smile. He laughed as he told me that his middle name was Pacelli – but that I couldn’t tell anyone.

The truth was, he had a lot of secrets, many of them dark.

I had to pinch myself to remember that the kindly-looking gent beside me had been a ruthless commander in the IRA, one of the most feared and ruthless terror groups in UK history.

“Martin was always one of the lads, and at the same time he stood out as being more articulate than most, more self-confident,” said Eamonn McCann, a former civil rights leader who grew up in McGuinness’s shadow.

“Obviously the pleasant exterior of Martin is not all that there is to him,” he said.

Atrocities of ‘The Troubles’

Born into poverty in the Bogside slums of Londonderry – or as he and fellow Irish republicans call it, Derry – in 1950, he grew up in the cradle of the province’s republican movement.

In the late 1960s, Londonderry’s Catholics took to the streets demanding civil rights and an end to Protestant dominance of Northern Ireland. They clashed with the overwhelmingly Protestant police force and, as the violence worsened, the British government sent troops to the province.

McGuinness joined the Irish Republican Army, the IRA, ready to fight.

“The first time I picked up a stone was in the Battle of the Bogside, which was 1969,” he said later.

By 1972, at the age of just 21, McGuinness was a republican heavyweight; an IRA commander under whose leadership policemen and soldiers were killed.

“A lot of important attacks were carried out when he was chief of staff,” said local journalist Liam Clarke, who tracked McGuinness’s rise through the IRA.

That same year, on what became known as Bloody Sunday, British paratroopers fired on angry demonstrators in the city, killing 13 unarmed civilians.

McCann says it was a seminal moment for McGuinness and the IRA: “Bloody Sunday, it could be said, made the IRA … (and) thereby made Martin McGuinness into a leader with a mass following.”

Later in life, McGuinness would only ever admit to having been an IRA commander that one day at the Battle of the Bogside, but he was never able to shake the perception that he’d had a hand in many atrocities.

“The biggest success the IRA ever had against the British army, the murder of 18 soldiers at Warren Point, that was carried out when Martin McGuinness was in overall charge of the IRA,” said Clarke.

In 1973, he was convicted and sentenced to six months in prison in the Republic of Ireland after he was arrested in a van packed with bomb-making equipment and ammunition.

As he was led away from the court, he yelled “we have fought against the killing of our people,” adding “I am a member of Ohglaigh na hEireann (the IRA) and very, very proud of it!”

Trading violence for politics

In the early 1980s McGuinness became an elected politician for Sinn Fein, the political wing of the IRA. But he didn’t do it alone – he had help from British spies.

Willie Carlin, a political agent for Sinn Fein, told his spymasters in London how he got McGuinness elected, fraudulently.

“I had people with wigs, coats, glasses, at polling stations all day from 9.00 in the morning until 9.00 at night. We stole over 2,000 votes to get Martin elected,” he said.

McGuinness told me he was never aware of just how he was elected.

According to Carlin, who was eventually pulled out of Londonderry by the UK government after his cover was blown, the British knew they needed McGuinness’s help to end the war.

“He delivered the IRA to the British government,” Carlin said.

At the time, McGuinness was one of the most feared men in Northern Ireland.

Another British agent inside the IRA told me of the terror McGuinness inspired in him: “He holds the power of life and death and that is it. He is God. He scared the **** out of me.”

‘No McGuinness, no ceasefire’

Eammon McCann says this was precisely why McGuinness was so important to the British government: He had the power to deliver peace

“No Martin McGuinness, no ceasefire – I think you can put it as strongly as that,” said McCann.

Even as the IRA launched bomb attacks in Northern Ireland and mainland Britain, McGuinness was in secret contact with British intelligence; in 1972, he was the youngest of six IRA leaders flown to London for covert talks with the government.

“Sometimes the people here are best suited to bring a conflict to an end, to get an agreement, are the very people that are a part of that conflict in the first place,” he told me in 2000.

But such actions weren’t without risks. “We were dealing with very devious people who had the capability to destroy me as a republican,” he said, “(to) bring about a set of circumstances where I could lose my life as a result of my participation in these talks.”

Twenty years after his first meetings with the government, discussions ramped up under then-Prime Minister John Major.

Through several years of high-profile, public peace talks, McGuinness and Sinn Fein President Gerry Adams could often be seen strolling the grounds of whatever government buildings they were meeting in, deep in conversation, planning their next move away from listening devices.

The risks eventually paid off, leading to 1998’s Good Friday Agreement, which called for power-sharing between Catholic and Protestants, and for paramilitary groups including the IRA to decommission their weapons.

“This has been a good day, after a few very bad days,” McGuinness said at the time.

Vindication at the ballot box

But the peace process got off to a shaky start, with IRA splinter groups continuing to plot and carry out terror attacks, including the bombing at Omagh in 1998 which left 29 dead and more than 200 wounded.

To the Real IRA and others who refused to lay down their weapons, McGuinness was a sell-out.

“Martin McGuinness is a Michael Collins waiting to happen, no doubt,” Carlin told me. Collins, a leading republican who negotiated with the British in the 1920s, was assassinated soon afterwards.

“Leading republicans away from the armed struggle and towards constitutional politics can be very, very dangerous business,” explained McCann.

But McGuinness never backed away from his new found principles of politics and peace, and vindication came at the ballot box: Sinn Fein’s popularity soared, and they became the most powerful Catholic party in Northern Ireland.

In 2007 after several years as Education Minister McGuinness rose to the post of Deputy First Minister alongside the IRA nemesis and Protestant firebrand Reverend Ian Paisley.

So warm was their public relationship – something generations had grown up never believing could happen – and so often were they seen laughing together, that they became known as the ‘Chuckle Brothers.’

The transformation dumbfounded some of his old enemies.

David Ervine, a former member of the Protestant paramilitary group the Ulster Volunteer Force, who, like McGuinness, later turned to politics, told me how he had plotted to kill him on a fishing trip. Ervine laughed as he told me, “I’m glad it didn’t work out.”

Historic handshake

McGuinness’s compromises continued: In 2012, he became the first in his party to shake hands with Britain’s Queen Elizabeth, a testament to how far this onetime republican terrorist had come.

But in early 2017 after 10 years of sharing power with Protestant politicians McGuinness abruptly resigned. He and his party no longer trusted the Protestant leaders who replaced Paisley after his death. “So I believe today is the right time to call a halt to the DUP’s arrogance,” he said.

He was ill, and it was a last roll of the political dice. He remained a republican through and through.

At the time I was driving the battle-scarred streets of Northern Ireland with McGuinness, he seemed to have long ago concluded he’d never see a united Ireland in his lifetime.

“I have always believed in myself,” he told me in 2000. “From the day I stood with the young people and the old people of Derry and threw stones during the Battle of the Bogside … from that moment on, I believed we could achieve important things.”

He never let go of that belief.