The failure of the much anticipated drug, which showed promise in earlier results, is being seen as a disappointing setback, but not the end of hopes to fight the disease.

On Wednesday, US drugmaker Eli Lilly announced that the Phase 3 clinical trial of its drug solanezumab did not progress as planned.

"Patients treated with solanezumab did not experience a statistically significant slowing in cognitive decline compared to patients treated with placebo," the company said in a statement.

Almost 47 million people live with dementia worldwide and that number is expected to double every 20 years to reach 131 million people in 2050, according to Alzheimer's Disease International. Dementia due to Alzheimer's disease is estimated to account for 60 to 80 percent of dementia cases.

The trial

More than 2,100 patients diagnosed with mild dementia due to Alzheimer's participated in the multi-national trial, called EXPEDITION3, which began in 2013.

In a statement, Lilly's chairman, president and CEO John C. Lechleiter said the company was "disappointed for the millions of people waiting for a potential disease-modifying treatment for Alzheimer's disease."

He added that the results would be evaluated to determine the impact on its other potential Alzheimer's drugs in the pipeline.

The company's share price dropped more than 10% on the New York Stock Exchange after the announcement. More details are expected to be announced on Thursday.

Attacking amyloid plaques

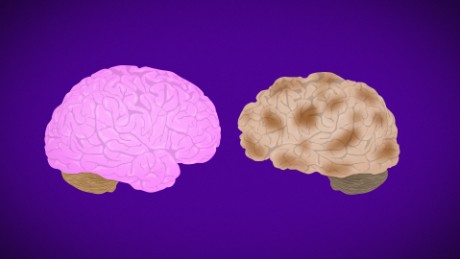

Like other anti-amyloid drugs, solanezumab was designed to reduce the build up of amyloid plaques on the brain, which are thought to contribute to the memory loss associated with Alzheimer's disease.

The results now bring that underlying biology into question.

"The failure of this trial is something that could be another step back for the amyloid theory," said Professor Bryce Vissel, Roth Fellow and Director of the Centre for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS).

However, while disappointing, the results will spur the scientific community to examine other potential cures for the disease, he said.

"One could call it the beginning of a next generation of efforts for treatment for Alzheimer's," he said. "We're getting a much deeper understanding of the disease and a more robust approach to curing it. Ultimately, this will bring about approaches to solve the disease within our lifetime."

Dr Mark Dallas, Lecturer in Cellular and Molecular Neuroscience at the University of Reading agreed. "While this is disappointing news, we will have to wait for the full data set to see if there are any nuggets of information that provide insight into the lack of effect of solanezumab," he said. "It's another setback for the Alzheimer's community, however the information we obtain from these setbacks is vital in our common goal of generating a novel treatment to tackle Alzheimer's disease."

Vissel said attention had now turned to the next big trial of a

drug called aducanumab by Biogen, which works by attacking plaques from another angle. The drug showed promise from preliminary results announced in September, though final results are still a while away.

For many, the failure of Lilly's solanezumab trials wasn't surprising.

"There is still no convincing evidence that shows a clear relationship between amyloid deposition and deficits in cognition in humans," said Professor Peter Roberts from the University of Bristol.

"All we really know is that evidence of amyloid deposition begins up to maybe 20 years before the onset of Alzheimer's disease. This might be a good indicator, but does not prove causality."

"This is disappointing but not a great surprise," added Robert Howard, Professor of Old Age Psychiatry at UCL who believes the decades of failed drug trials highlight the challenge that still lies ahead. "What we have learned from several decades of research and hundreds of failed Alzheimer's disease trials is that no matter how promising the basic and early phase data, all that really matters is the results of these late phase effectiveness trials."

The US Alzheimer's Association said it hoped ongoing tests for solanezumab and other anti-amyloid agents would continue.

"These other programs have different ways of acting on the amyloid pathway and some are also addressing the disease at a much earlier stage when these drugs may still prove to be effective," it said.

As populations increasingly live into their older years, the need to tackle the problem remains.

"Dementia is society's biggest health challenge and we've seen time and again that developing effective treatments is incredibly difficult," said Jeremy Hughes, Chief Executive of Alzheimer's Society. "This is only one drug of several in the pipeline and they aim to tackle dementia in different ways, so we should not lose hope. Dementia can and will be beaten."

CNN's Meera Senthilingam contributed to this reporting.