Women wail in the background as the camera pans across the scene.

“Oh brothers, look at this, look,” the narrator says, as he films the remnants of a burned house, bodies clearly visible sticking out of the mud and ash.

The disturbing video is one of a handful that have emerged from northern Rakhine State, in Myanmar, where human rights groups warn of widespread human rights abuses.

Hundreds of homes have been destroyed in multiple villages amid an ongoing crackdown by the Myanmar military following violence last month, according to Human Rights Watch.

Authorities claim the fires were set by local militant groups, and have disputed HRW’s account.

Authorities in neighboring Bangladesh said dozens of people have attempted to flee across the border in recent days.

Violence and silence

The most recent spate of violence began in early October, when soldiers and police officers were killed by a group of 300 or so armed men, according to state media reports.

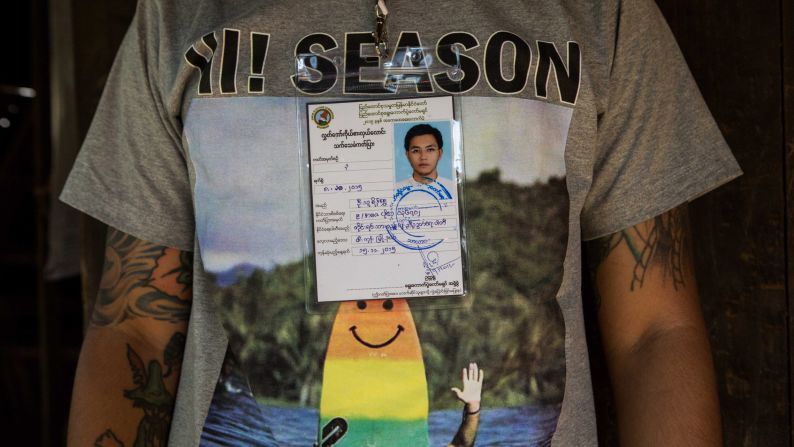

That sparked an intense crackdown by the Myanmar military in which dozens of people have been killed and at least 230 arrested. Rights groups estimate the total death toll could be in the hundreds.

Rakhine State is home to a large population of Rohingya Muslims, a stateless ethnic minority that has faced discrimination and persecution for years. The Myanmar government’s official position denies recognition of the term “Rohingya” and regards them as illegal Bengali migrants.

Throughout, many have looked to Myanmar’s civilian government, and particularly Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, to act as a check on the military.

The National League for Democracy (NLD), led by Suu Kyi, won a landslide victory in elections late last year, ending more than two decades of brutal military rule.

Landmark elections in Myanmar

However, under a constitution drafted by the former junta, the military retains 25% of the seats in parliament, and control of security matters.

The Myanmar Armed Forces, or Tatmadaw, is led by Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, who was handpicked by former junta strongman Than Shwe to succeed him in 2011.

While analysts did not dispute that the military is leading operations in Rakhine, they expressed disappointment with the government’s lack of action.

“That the government has simply flatly denied human rights violations are taking place does not bode well for the NLD,” said Matthew Smith, founder of Bangkok-based Fortify Rights.

“When these types of violations are being committed by the government it is reason for concern for everyone in the country.”

Risk of instability

As violence in Rakhine has persisted, Kofi Annan – the former United Nations secretary general who currently leads a Myanmar government commission – warned it is “plunging the state into renewed instability.”

United Nations envoy Zainab Hawa Bangura has also expressed grave concern over allegations of rape and sexual assault of women and girls in Rakhine as part of a “wider pattern of ethnically motivated violence” in the region.

In a statement this week, the Myanmar President’s office, citing military information teams, “refuted the fabrications” published by foreign media and blamed violence on terrorist groups.

Presidential spokesman Zaw Htay, who previously served the country’s military rulers, denied reports of troops burning houses and allegations of rape and sexual assault during a press conference Wednesday.

He promised that the government would “cooperate with the media for sensitive conflict reports in the future.”

Human Rights Watch has repeatedly criticized the Myanmar government’s denial of access to the region for human rights monitors and journalists.

CNN has repeatedly reached out to Suu Kyi’s office for comment but hasn’t received a response.

Disappointment

In an interview with CNN in September, Suu Kyi said her government was having “a lot of trouble trying to bring about the kind of harmony and understanding and tolerance that we wish for.”

“This is not the only problem we have to face, (but) this is one on which the international community has focused,” Suu Kyi said, pointing to the establishment of Annan’s commission and the lifting on some restrictions on the movement of Rohingya as actions her administration has taken.

Nevertheless, at times Suu Kyi’s silence on the issue has been deafening. Smith described the current response as “deeply concerning.”

“I don’t have words to describe the disappointment with her government,” he said.

While he was skeptical over how much power the civilian government had to influence military activity in Rakhine state, Anthony Ware, a Myanmar specialist at Australia’s Deakin University, said Suu Kyi’s silence was a “long term consistent trend.”

“We have not seen a lot of leadership on this issue from (Suu Kyi or the NLD),” he said.

With the military in full control of security issues, and backed up by its 25% base in parliament, its unclear how much effect a more vocal NLD government could have.

There is also strong support among the country’s Buddhist majority for anti-Rohingya actions and angry anti-Muslim rhetoric has increasingly become part of mainstream discourse in Myanmar, led by ultra-nationalist Buddhist monks.

“Muslims are perceived nationally, even by most of the ethnic minorities, as a threat to Buddhism and threat to national security,” Ware said.

Military abuses

Before and after the country’s transition to democracy, the Myanmar military has been accused of torture, rape, and the systematic abuse of child soldiers.

Rights groups have documented continued widespread abuses against ethnic minorities, particularly in Rakhine and Kachin states.

“All of the key issues in Rakhine State and activities are under military control,” said Ware.

“While there are armed elements in Rakhine, and while there are significant fears of a loss of control of the border and potential international Islamic terrorist influence, the military will not allow anyone else to have much of a say.”

Smith said the military is carrying out a “clearance operation” against Muslims in the region, and warned that international crimes may be being committed.

“We’ve documented how Rakhine State authorities were talking about a plan to demolish Muslim-owned properties prior to the October attacks. It would appear that strategy is in some ways being carried out in another context,” he said.

CNN’s Bex Wright, Vivian Kam and Joshua Berlinger contributed reporting.