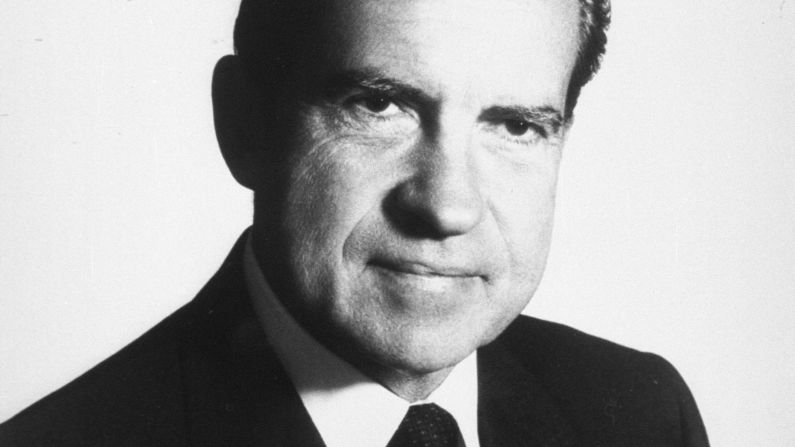

Editor’s Note: Tim Naftali is a CNN presidential historian and clinical associate professor of history and public service at New York University and was the founding director of the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum. A biographer of George H.W. Bush, he is working on a new history of the Kennedy presidency. For further information about Watergate and Richard Nixon’s abuses of power, visit here. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his.

Story highlights

Tim Naftali: Trump team should note unique risk of Nixon's instability

Advisers often disagree, even erratic presidents act independently, he says

When Richard Nixon had a hard time sleeping during the 1968 campaign, he would take a sleeping pill, have a scotch and start calling people. “[The calls] were filled with late at night anxiety,” recalled campaign aide Leonard Garment in 2007 for the Nixon Library, “fear, sleeplessness, and the knowledge that he had to get to sleep. …” These calls came at midnight or later and they often involved the candidate just rambling.

The erratic behavior did not end with the campaign and soon became a problem for the new administration. White House chief of staff H.R. “Bob” Haldeman concluded that he had to design a system to protect the President from himself. As Haldeman would describe it in his memoir, “The Ends of Power,” it involved a “conspiracy to keep the dark side down; the light side up.”

The tipping point for Haldeman came only six months into the administration, when Nixon ordered wiretaps on every sub-Cabinet official who was in the White House Situation Room. Nixon also dreamed up a scheme that had staffer Pat Buchanan work up a fake National Security Council document to leave in the Situation Room to see if it, too, leaked.

“I realized that many problems in our administration arose not solely from the outside, but from inside the Oval Office — and even deeper, from inside the character of Richard Nixon,” Haldeman wrote years later.

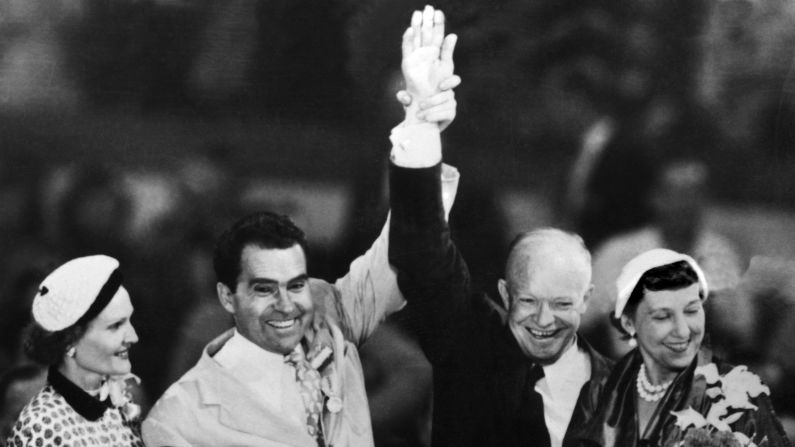

It is much too early to say whether Donald Trump will challenge Richard Nixon for the distinction of being the most unstable personality to inhabit the White House in the modern era. His behavior during the campaign, however, does raise some red flags. So, as Donald Trump begins putting together his core group of about 30 advisers and top administration officials – a chief of staff, Cabinet members – during this transition, it is useful to see how the US government evolved 40 years ago to meet the challenge of an erratic commander in chief: where the effort succeeded and, sadly, where and why it ultimately failed. The consequences of that failure would have not only domestic but also major global consequences.

One of the persistent myths about our system of government is that the presidency is as much about the advisers around the President as the individual in the Oval Office. This is a case often made when major party candidates lack foreign policy experience. “Don’t worry about X,” goes the argument, he has good advisers.

Views on Election 2016

But history, which can speak out of both sides of its mouth on many things, is quite clear on the limits of the significance of presidential advisers: Consensus is rare, the top advisers more often than not disagree, leaving the agony of decision to the President. Bob Gates’ beautifully written memoir on his years as secretary of defense for two presidents, for example, underscored that it was President Obama who decided how to go after Osama Bin Laden, when his advisers —including Gates — could not agree.

The Constitution makes the President, or chief executive, what George W. Bush later famously called “the Decider.” The election of Nixon meant that for four years, at least, there would be a psychological instability at the center of that strong executive.

Fortunately for the nation, Nixon chose strong individuals to run the Pentagon, who were self-confident enough to try to shield the armed services from an erratic commander in chief. Melvin Laird, a former congressional colleague of Nixon’s, was a grounded man with an independent power base who was prepared and clever enough to find ways to prevent bad presidential orders from taking effect.

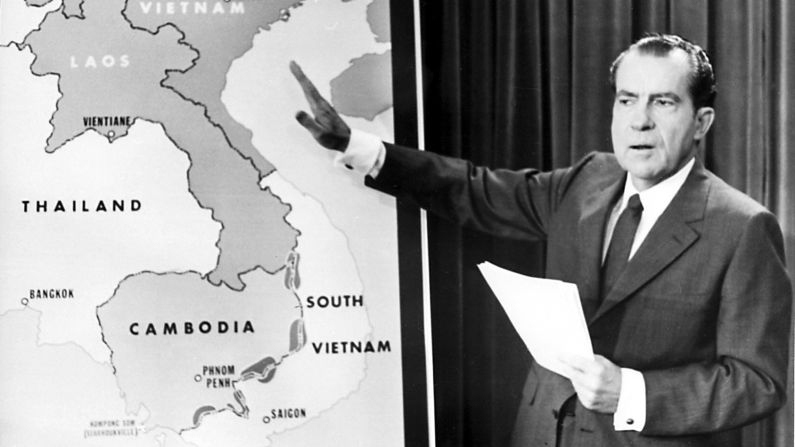

In his authorized biography, former Secretary of Defense Laird tells the chilling story of a late-night call from Nixon in September 1970. The radical Palestinian terrorist group, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, had just hijacked four planes and flown two of them to an abandoned British airfield in Jordan. The Nixon team debated what to do. Later, in the residence, Nixon apparently lost his patience.

“[B]omb the bastards,” said Nixon, slurring his words, and then ordering the use of jets from the carrier Independence. Laird thought the order nonsensical. The only likely effect would have been to ensure the deaths of the approximately 180 passengers held hostage, when at that point they were not actually in any great danger. But Nixon wanted to send a signal to the Soviets, who sponsored the Popular Front.

Fortunately for the hostages, all of whom eventually made it home alive, and for US Middle East relations, Laird prevaricated. “I told him,” Laird later recalled for his biographer Dale Van Atta, “we would do the best we could. I didn’t have a big argument about it; I just didn’t do it.”

In the waning days of the Nixon administration in 1974, James Schlesinger ordered the Pentagon not to implement a presidential order unless it came directly from Richard Nixon. He then told Gen. George Scratchley Brown, chairman of the Joint Chiefs, “that … all the service chiefs should be aware that if there were any messages from the White House, I should be informed immediately.”

Schlesinger worried that Nixon had loyal lieutenants who might want to move troops around the Washington area as a show of force. By that stage in his career, Nixon would not issue this kind of order directly but had created a climate in which someone might order it for him.

The efforts by Haldeman, Laird and Schlesinger to contain Nixon’s instability were only as good as the men around the President. Haldeman’s 2-year-old containment system ultimately broke down because Haldeman was himself not a good man.

He shared Nixon’s hatred of political opponents, his racism and his anti-Semitism, doing nothing to stop the creation of the Plumbers unit, the hiring of Teamster “thugs” to do physical harm to anti-war demonstrators, the politicization of the IRS and the counting of and discrimination against Jewish Americans in the part of the Labor Department that determines the unemployment rate, a so-called “sensitive area.”

A year later, in 1972, at the request of the President, Haldeman would loyally authorize a “dirty tricks campaign” and, also likely at Nixon’s request, a political spying unit that repurposed the Plumbers team. Lacking anyone in the White House with the authority and moral center of Melvin Laird or James Schlesinger at the Pentagon, the Nixon administration was soon overwhelmed by the consequences of the stream of criminal orders from a President who lacked self-control.

As Hillary Clinton explained in her concession speech, we owe our new President “an open mind.” Nevertheless, the choices Donald J. Trump makes for his Cabinet and his White House team will say a lot about how he intends to govern and be governed.

Does he choose a Cabinet of equals, who might be able to stop him from making the inevitable rookie mistakes? Will his inner circle at the White House be dominated by people who magnify the darker impulses he expressed in his tweets or by those who would contain the anxieties, doubts and prejudices for the good of the man and the country he will very soon lead?