Fred Dewilde spends his days drawing body parts, sketching internal organs in pen and ink for medical trainees and science laboratories.

But last November, crouched on the bloodied floor of the Bataclan in Paris, the graphic designer came closer than he ever imagined to the viscera he makes a living depicting.

Dewilde, who goes by a pseudonym, was at an Eagles of Death Metal concert when ISIS-linked terrorists burst in, killing 89 people. The raid was one of a series of attacks a year ago this weekend at bars, restaurants and venues across the French capital that left 130 people dead.

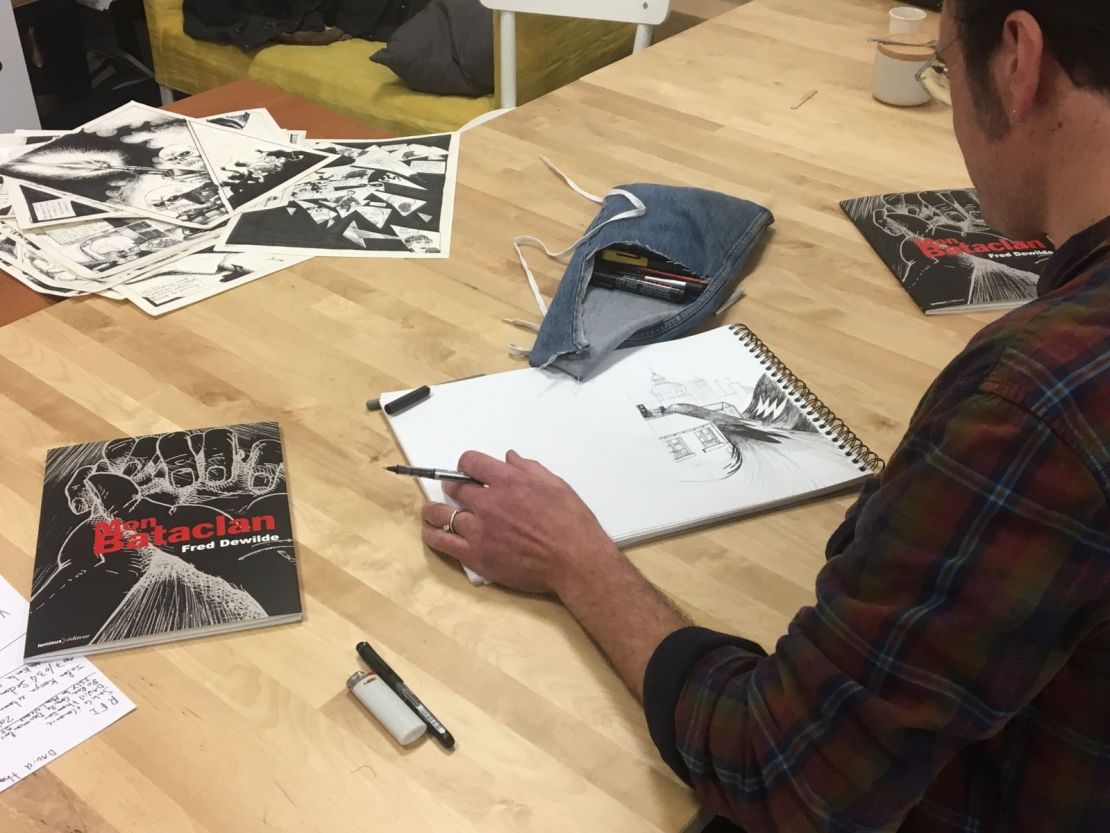

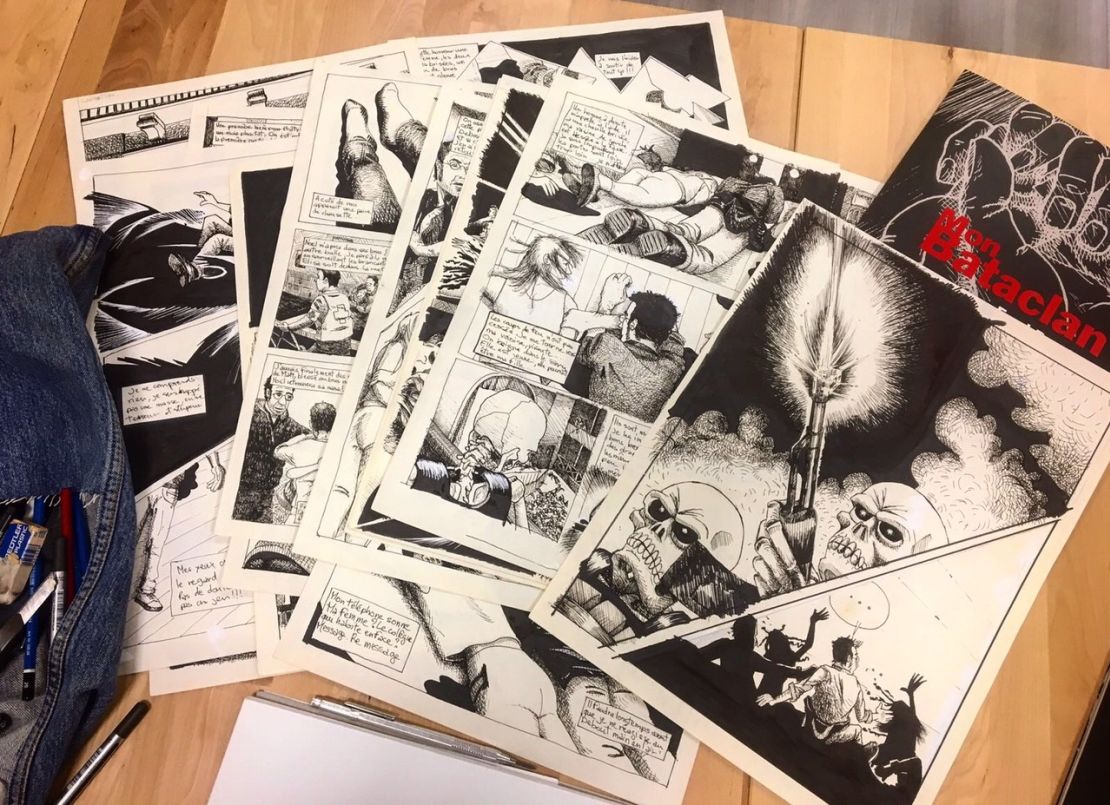

Twelve months on, the 49-year-old father-of-three has turned his ordeal into a book; using his background in illustration to create a graphic novel showing the Bataclan attack.

“I feel alive when I draw,” he tells CNN, explaining that returning, in images, to that dark night has helped him recover from the trauma of what was to be a fun couple of hours.

Friday night interrupted: Survivors tell of carnage

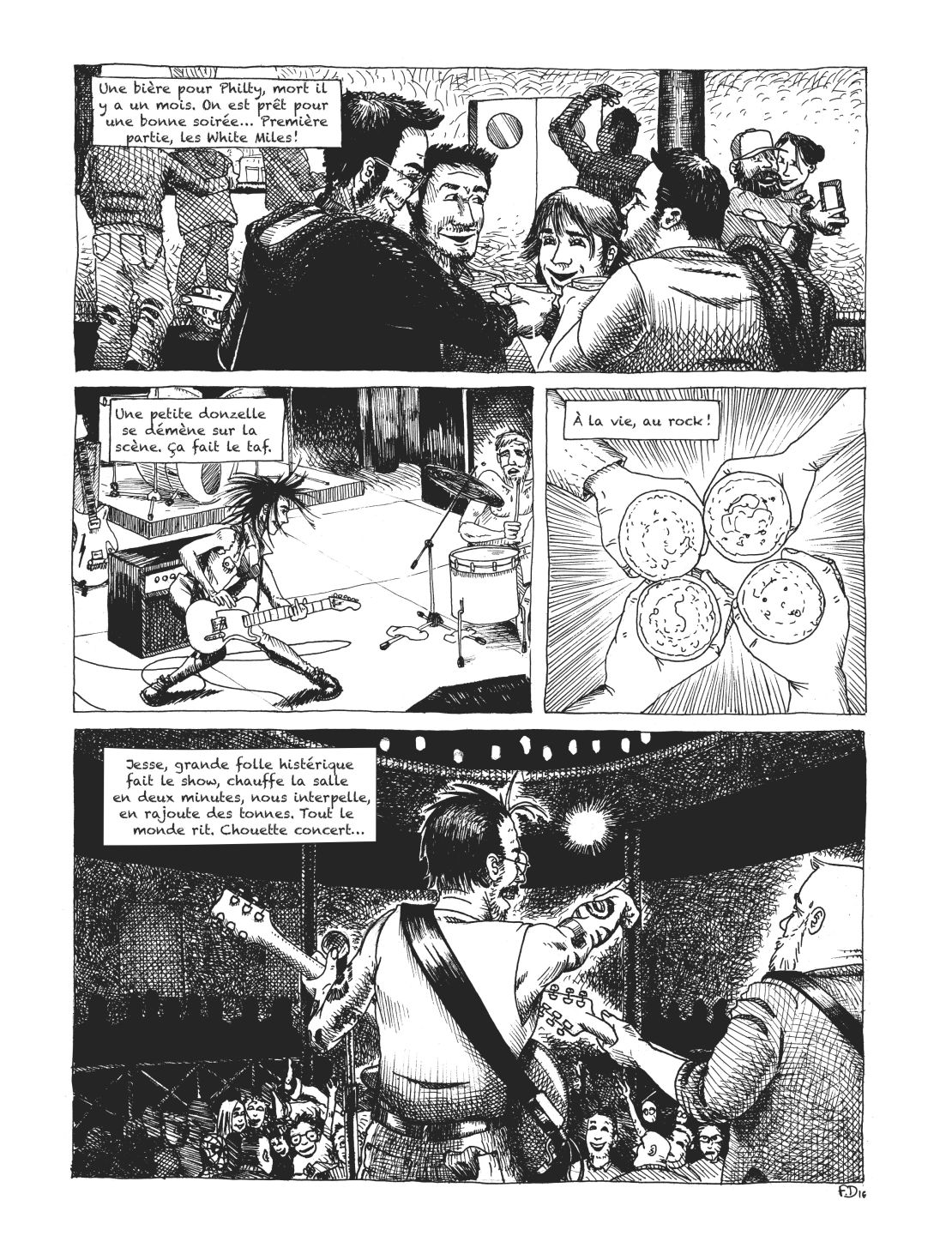

The small group of friends met for drinks early; Dewilde says he liked to arrive at gigs in plenty of time to see the support act, “it’s always a great opportunity to discover new bands,” but EODM were the main attraction.

“I knew the band pretty well, so I knew it would be fun. It was supposed to be a cool night out, rock ‘n’ roll, drinking with three buddies. And then …”

A few songs into EODM’s set, shots rang out, and “the ambiance changed in a snap of the fingers … to hell.”

At first he didn’t understand what was going on, thinking that the noise and commotion were all part of the show.

“It took me a lot of time to realize that it was really an attack, that people were dropping dead around me … that it wasn’t a game anymore.

“I met the eyes of a dead person and at that moment I understood.”

Inside the Bataclan: A night of terror

‘Perfect target’

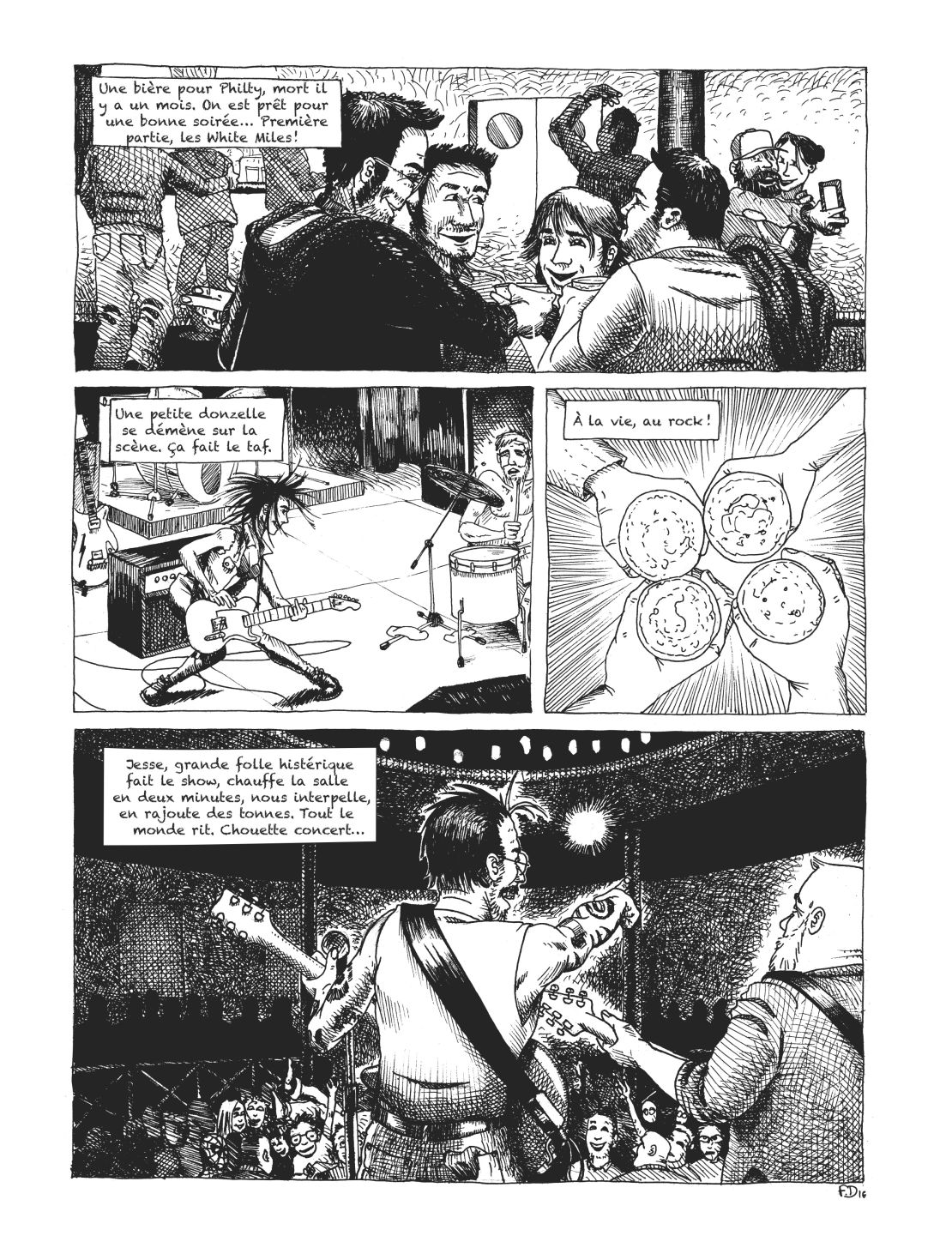

Two of his friends had been standing near a door when the shooting broke out, and were able to escape quickly, but by the time Dewilde had grasped the seriousness of the situation he realized he would be a perfect target.

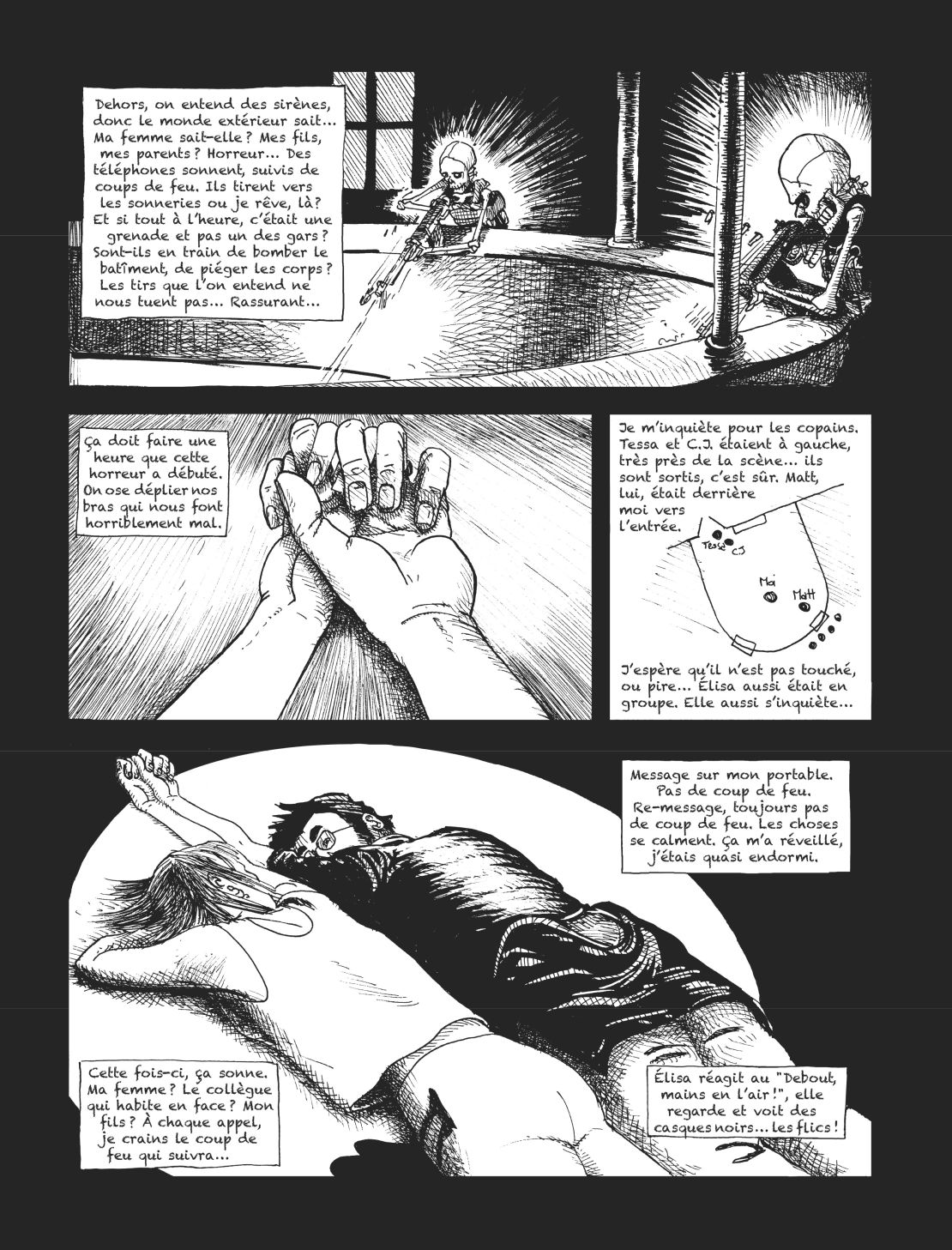

In desperation, he lay down on the bloodied floor next to an injured woman, who he calls Elisa in the book.

“I did not see at first that she was hurt,” Dewilde recalls. “I introduced myself, told her my name was Fred. We managed to whisper a few words, which helped us not to panic, to stay strong.

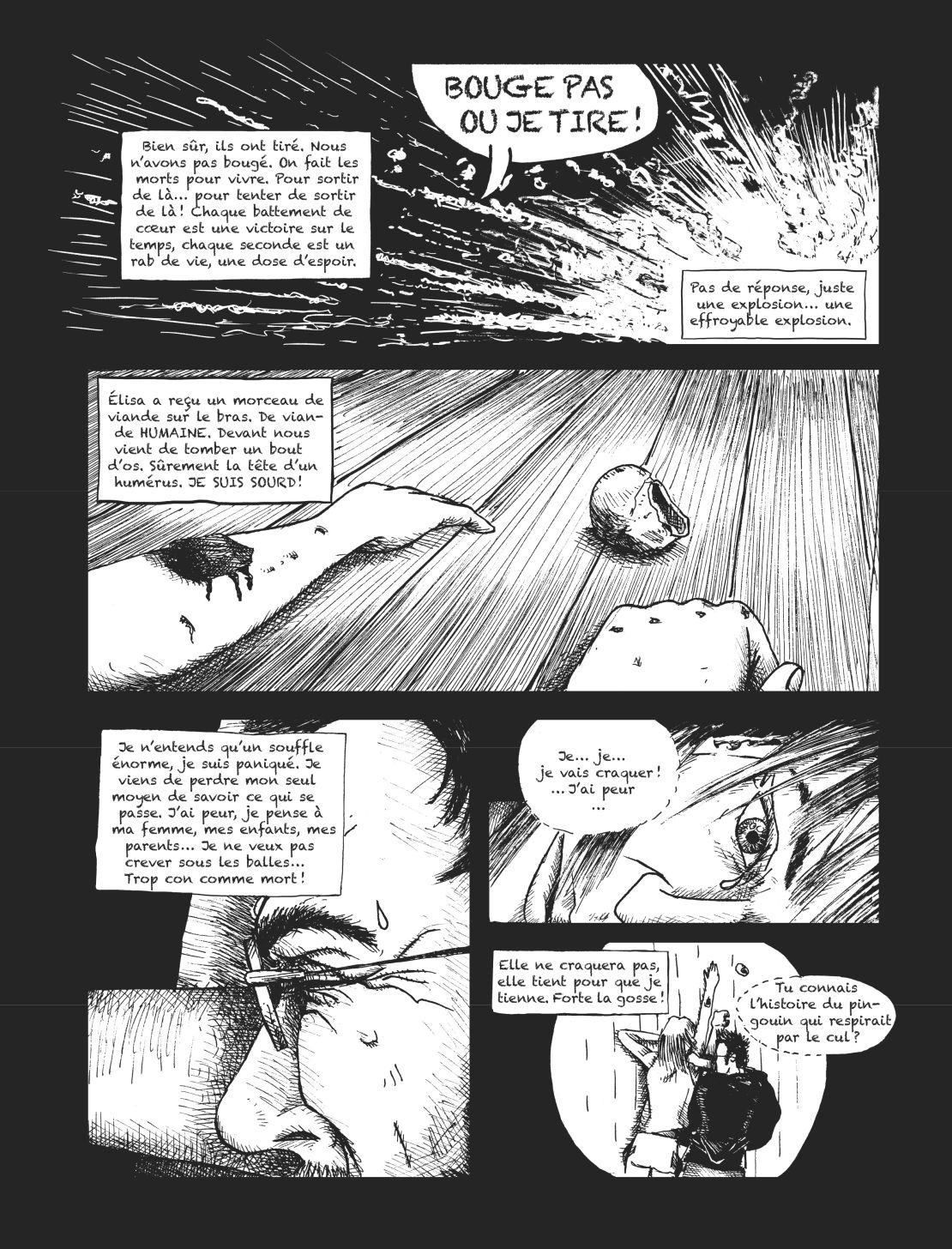

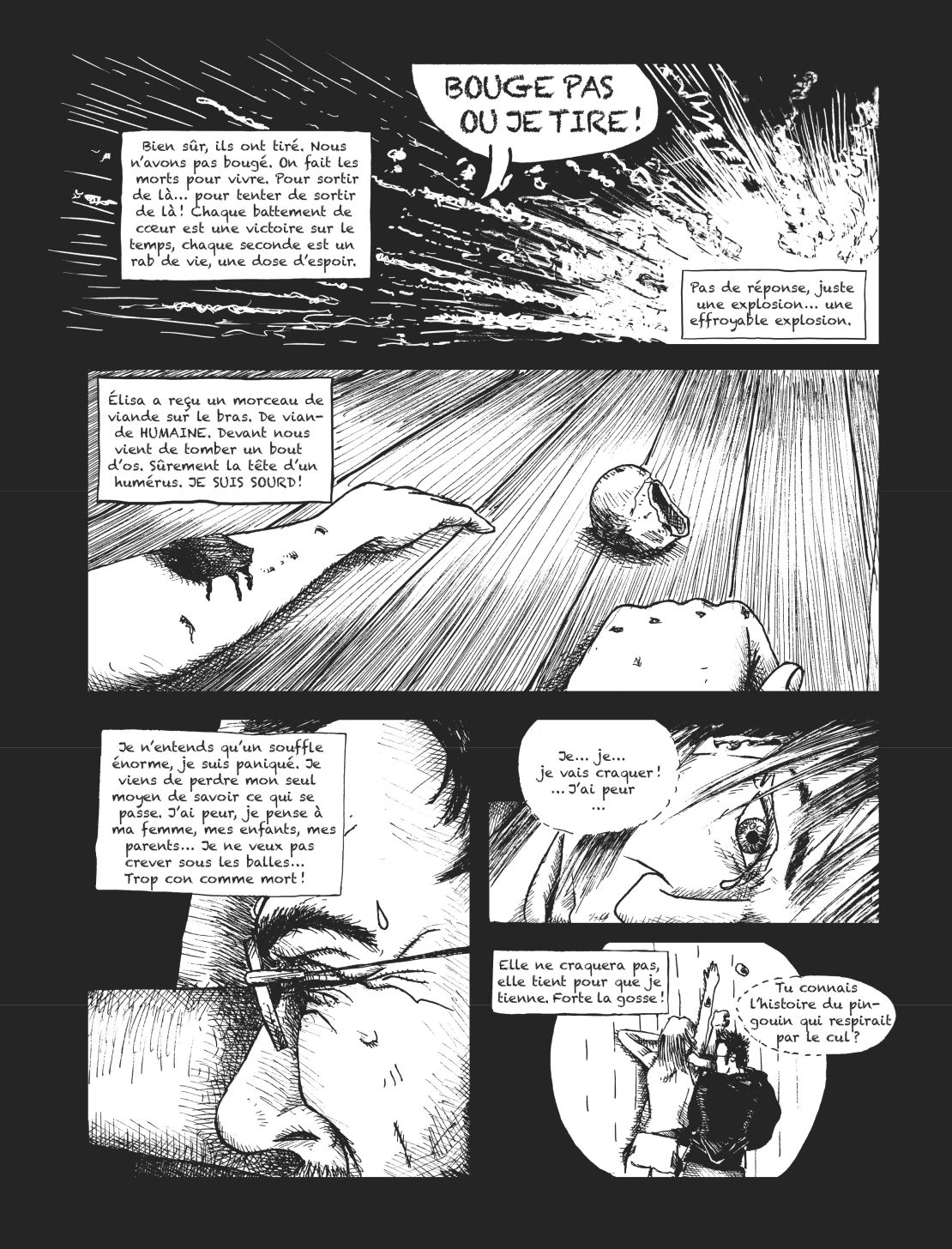

“We did not move a muscle, even when the terrorist exploded, we did not move. We were playing dead to stay alive.”

He credits his new found friend with helping him find the strength to make it through.

“What saved me at that moment was having Elisa in front of me,” he says. “[Her presence] made me want to keep on going, gave me the force to take on the role of a father.”

EODM: Fans died trying to save their friends

‘Completely destroyed’

After what seemed like hours, the police arrived to rescue those who had survived.

Dewilde’s third friend had been at the back of the room and was hit by one of the attackers’ bullets.

“He was shot in the arm – nothing too severe, as the bullet did not touch his bone, so he was back on his feet pretty quickly,” he says. “But it could have ended badly for all four of us.”

In the days and weeks that followed, Dewilde struggled to make sense of what had happened.

“I came out of there alive, but I was no longer alive inside,” he says. “I was very lucky to get out, don’t get me wrong. But you are completely destroyed when you get out of there.

“The look in my wife’s eyes, my children’s eyes, the laughter and everything else … is what brought me back to life.”

In memoriam: Paris attacks victims remembered

Drawing as therapy

Eventually, Dewilde began drawing what he had seen and heard that night in the Bataclan as a way of processing what he’d been through.

“I drew what I had in my memory, the way I saw things. That’s one of the reasons why the title came to me naturally – it was ‘My Bataclan,’ – it didn’t matter that it would be exactly the same decor, the exact number of terrorists … that Jesse (Hughes) looked like Jesse or not, that wasn’t important.”

Putting pen to paper and drawing his way through his experiences helped him “re-appropriate that night,” and to feel better, he says.

“I was considering it as two hours stolen from me, two violated hours,” but by creating the comic book, “it became mine.”

He says he is still plagued by memories: “It’s completely fresh, I still have a foot in the Bataclan. I can’t forget. I have seen an horrific vision that I wish I had never seen.”

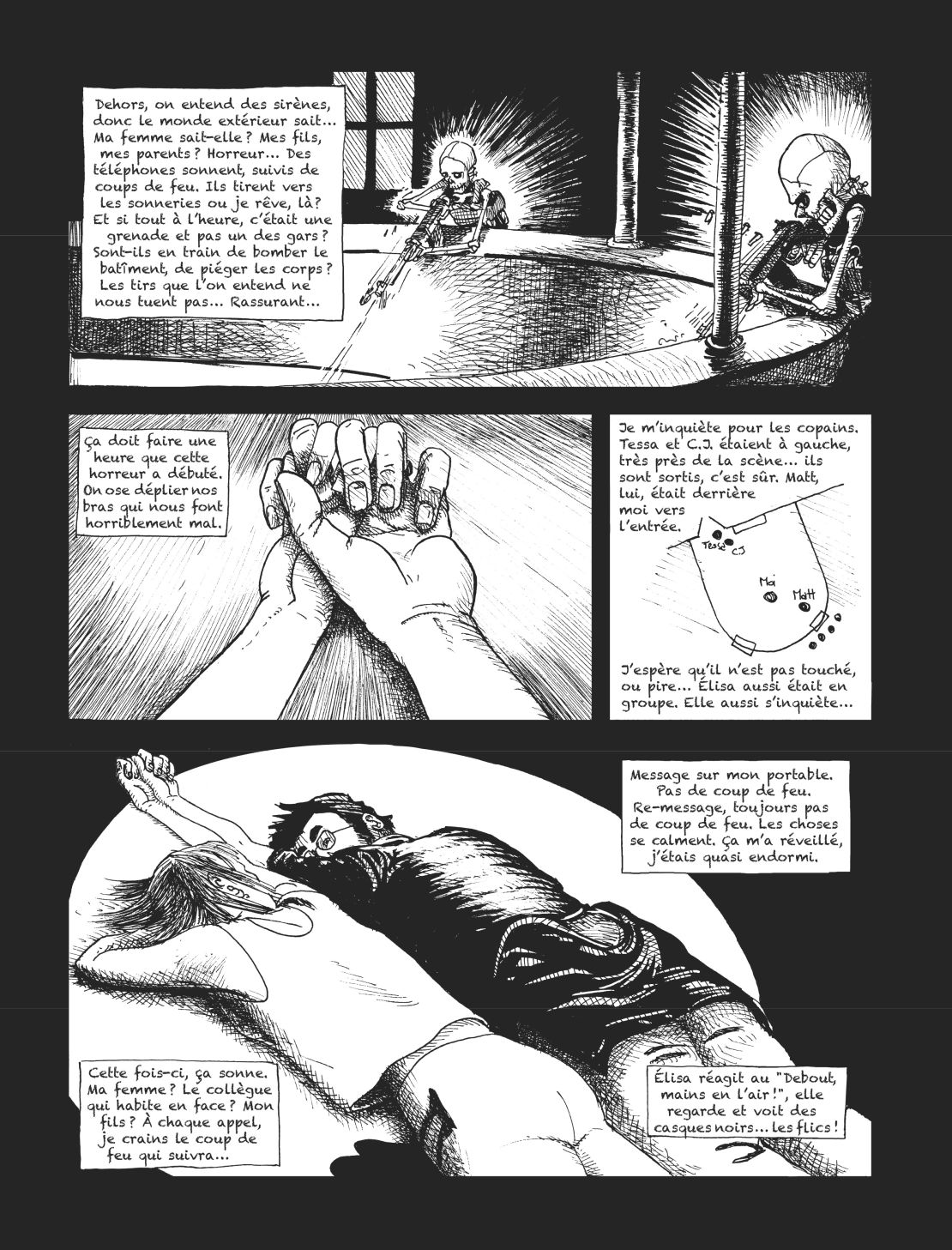

Many of the grimmest things he witnessed did not make it into the book. Instead, the story focuses – briefly – on small details, such as the piece of human flesh and fragment of bone that landed near him after one of the suicide bombers blew himself up.

“For me it was revealing of the whole horror without telling much,” he says. “In speaking only about that, I was implying so many things, and didn’t need to go into further detail.”

Terrorists as skeletons

Even with a conscious decision to avoid gratuitously gory imagery, he still struggled: “Each drawing was a fight, because I lived through it all again in drawing it … it was as violent as when it happened.”

In his book, the Bataclan’s attackers are depicted as skeletons, recalling the four horsemen of the Apocalypse. Dewilde says this was a deliberate way of showing the stark difference between the bombers and those they were targeting.

“We were alive, we were enjoying life,” he explains. “In my view, someone who comes like that to do mass killings is someone who is dead inside. There is no humanity, no trace of empathy, there is nothing of what makes life.”

And while for many, memories of that night remain drenched in color: the blue of the emergency vehicles’ flashing lights, the bright orange of rescue workers’ jackets and the red of so much blood, Dewilde’s depiction is strictly monochrome.

“I prefer black and white to colors,” he explains. “But it’s essentially because I started drawing the cartoon as a draft, and quickly realized that I would not be able to draw it again. It was not possible.”

Once he had finished the images, he pondered colorizing them using a computer, but “the only color that was coming to my mind was red and that wasn’t interesting.”

A year on, he still sees Elisa once or twice a month. The pair have become firm friends.

“It’s funny, because we know each other intimately,” he says. “She knows the human that I am and I know what kind of human she is, but we still don’t know each other’s taste. We are starting to rediscover each other, to learn to know each other simply, on a basic level.”

Paris lost much, but kept joie de vivre

Shared recovery

He meets up with other fellow survivors regularly.

“We don’t need to tell each other everything and at the same time, we can precisely say everything. We know what the other has seen, we can share sordid details with each other and it won’t shock anyone since we have both seen it.

“It’s like people who have experienced a combat zone, like a soldier who comes back – he is not going to talk about everything he has lived through, everything he has seen. Another soldier will know.

“We can help each other in full knowledge of the facts. ‘You don’t feel great today, but it’s okay; you have seen what we went through. Tomorrow, you will feel better.’”

Surviving the attack has taught him that “you have to enjoy the now, you have to enjoy every day,” he says. “I was already the kind of person to look at the small birds in the park. It has reinforced the importance of life in life.”

However, after a 40-year love affair with rock ‘n’ roll and the blues, he hasn’t yet been able to return to the gigs he used to adore.

“I didn’t succeed to attend one concert all year,” he says. “I am not yet in a state that enables me to go to concert, after [the last one] was a catastrophe.”

‘It was perfect’: Eagles of Death Metal complete Paris show

Turning the page

On Sunday, when people gather to lay flowers and unveil plaques at the various attack sites across Paris, Dewilde says he will likely be with other survivors at some kind of unofficial commemoration, away from TV cameras and politicians.

“I am not going to go the ceremonies because … they are simply a ‘we need to pay a tribute’ thing … I have the feeling they are turning a page, whereas I think, ‘No, we still need to think about all that, if we want to prevent it happening again.”

Dewilde says he is determined to do all he can to battle all kinds of fanaticism, and urges to others to join the search for a way forward.

“When some people have decided to kill their neighbors, because that’s what it is in the end, we need to reflect on it … we absolutely need to think about all that and know where we are going.

“For me, what I have seen gives me even more of a will to fight against all that.”

Océane Cornevin and Camille Verdier contributed to this report.