‘Too afraid to ask’

A brother’s death at Columbine, 1999

Left alone with her parents, Christine Mauser worked hard not to fall apart. If she had to, she tried to do it alone. She couldn’t have them worrying about her.

Sometimes she’d overhear them losing it in the next room. She didn’t have the words to comfort them and feared that anything she’d say would make matters worse. So she sat frozen, wracked with guilt for ignoring their cries. On occasion, though, she allowed herself to turn angry. She was holding it together, why couldn’t they?

Christine was only 13 when the quiet and exceedingly normal life she and her family enjoyed in Littleton, Colorado, shattered.

On April 20, 1999, two heavily armed students went on a shooting rampage at Columbine High School. They murdered 13 people and wounded two dozen others before killing themselves. Among the dead, gunned down in the school library, was Daniel Mauser, Christine’s older brother, at the time her only sibling. He was 15.

Nearly two decades have passed. Christine, now 30 and living in Beaverton, Oregon, struggles to remember the sound of Daniel’s voice; their shared moments and conversations only come to her in snippets. But the memories surrounding the school shooting that robbed her of her innocence? Those will never go away.

Seventh-grade Spanish was letting out when an administrator at her middle school herded Christine and her classmates back into their classroom. It had to do with something that was happening at the nearby high school, though no one would say more.

“We were entering something they called ‘lockdown,’” she says. “I don’t recall any of us having any idea what that meant.”

The longer they waited, the more questions the students had. Eventually the teacher turned on the television. With the rest of America, Christine and her classmates watched the breaking news with confusion. She saw students being escorted out of the high school. The details from inside were still a mystery.

“There could be up to 20 fatalities,” Christine remembers her mom saying hours later, when she was picked up at school. “I didn’t know if fatalities meant deaths or injuries, and I was too afraid to ask.”

The house filled with neighbors and family friends. She remembers her father making repeated drives to the high school, desperate to pick up his son. Returning from one of his last trips, he dissolved into screams and tears. A terrified Christine was whisked off to stay the night two doors down.

The neighbors set out to distract her. They ordered pizza and turned on movies. Though it became harder to do so as the hours passed, she tried to convince herself that Daniel was just hiding in a closet, too afraid to come out.

Daniel was the more introverted of the two Mauser children. He was a voracious reader who loved science and math. He ran cross-country and was in both the debate and chess clubs. He was “coming into his own,” Christine says, and at the time of his death was earning straight As.

Unlike her brother, who didn’t like to be filmed or photographed, Christine was into acting and enjoyed being on stage. She surrounded herself with a bigger group of friends than he did. They bickered, as siblings do, and she admits she could be the annoying little sister. She laughs remembering the time she recorded him talking to friends, and then passed over the evidence so her parents could hear him saying bad words.

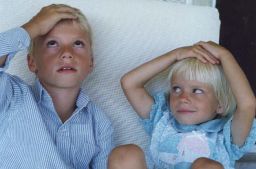

No matter their differences, they loved each other. Photos from their childhood reveal two towheads, laughing beside one another.

Reality hit the next day around noon, when officials showed up at the family home.

“They told us my brother was among the dead,” Christine says. “I don’t really remember anything they said after that.”

In an instant, she became an only child. It was a role she hated, not least of all because she couldn’t bear to see her parents in so much pain. For a while, she insisted that a friend sleep over every night.

“It sounds horrible, but you almost don’t want to be alone with your parents,” she says, “because watching them go through that is the worst thing in the world.”

Her father, Tom Mauser, doesn’t remember how he and his wife spoke to Christine during this time, but he knows they struggled.

“It was a major problem for us,” he says. “It’s not something you’re prepared for. … I don’t think I had the words or knew how to counsel her.”

Plus, they felt like the world had crashed on their shoulders. They had a child who was still alive, thank God, and turned their focus to their grief.

At first the kids in school showered her with kindness – even stuffed animals. But they couldn’t really look her in the eye. Truth is, she didn’t want them to. She had changed overnight.

“I remember just how awkward I felt, and how different I felt,” she says.

And in middle school, being different can mean trouble.

There were students who stared, watching her every move. If she cracked a joke or laughed in a desperate attempt to feel human, they looked at her stunned. On field trips, if the school bus rolled past Columbine High, their heads whipped around to monitor her reaction. She refused to be a mess in front of them, but the more she tried to act normal, the weirder she seemed – which only increased the gawking, her anxiety and, eventually, their bullying.

She withdrew from others and gave up the stage. After Columbine, the last thing she wanted was to be the center of attention.

It wasn’t that she was “all sunshine and rainbows” before her brother’s killing, but she emerged someone else. Irrational fears consumed her, as did an obsession with death. Like many children who lose a sibling, she convinced herself she wouldn’t live beyond the age her brother died.

'Concentric circles of pain'

She knew her concerns were illogical and didn’t want to alarm anyone, so she kept her dark thoughts to herself. Still, rumors circulated at school that she was going to kill herself.

Christine couldn’t articulate what she needed and wanted. Sometimes she felt like she and her parents walked around their house on eggshells.

Her mother, an introvert like Daniel, often retreated. Her father became an activist, rallying for better background checks and protesting the National Rifle Association. While she was proud of his work, it brought new forms of unwanted attention. She answered the phone when the first hate call came in and was cussed out by a stranger.

Some kids at school lectured her about the Second Amendment and told her what her dad was doing was wrong.

“I was so taken aback I just didn’t know what to say.”

Near the end of middle school, when being there became unbearable, she was pulled out and home schooled for the rest of the year. There was no way she could attend Columbine High, so she was given a special provision to attend high school outside the district. She craved anonymity. She needed people to know her for who she was – and not for what her family had been through. By 17, she says she began to find her footing again.

A big part in helping Christine and her family was Madeline, the 11-month-old baby they adopted from China a little more than a year after they lost Daniel. When her parents first proposed the idea of adoption, Christine was immediately on board.

Madeline proved a bright light in the darkness, a needed bundle of pure joy.

“We still felt a lot of the same pain and heartache and everything like that, but she was kind of just a different force,” Christine says. “I was so grateful to have her there and to be a big sister.”

No matter the positive forces and the years, however, Columbine doesn’t go away.

A book by one of the gunman’s mothers was released this year. Random Facebook friend requests pop up from people she calls “Columbine groupies.” She ignores them all, but feels sickened by those who use images of the killers as their profile photos.

Though married and a stepmother, she recalls those awkward moments from her single days when dates – having Googled her – would bring up Columbine. This piece of her past also resurfaces in a flood of emotions every time there’s another school shooting. After the 2012 massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School, she couldn’t eat for days.

When her stepdaughter, Bethany, mentioned having “intruder training” at school, she held her tongue. The 9-year-old explained it was done in case “a robber comes to your school.” Christine didn’t have the heart to tell her the truth.

Christine still holds onto Daniel’s copy of J.D. Salinger’s “The Catcher in the Rye.” It’s stamped in the back with “English Resource Center Columbine High School.” She didn’t go to that school, nor does her sister Madeline, who’s now 16. All these years later, her parents still can’t bear to pick up a child there.

Her brother has been gone longer than he was here, and Christine feels as if she’s lived two lives. She’s not who she was when she lost him. When she sees adult siblings being best friends, she can’t help but feel a bit bitter. She can’t help but wonder what might have been had Daniel lived.

– Jessica Ravitz, CNN

‘She never fell in love’

A sister’s accidental shooting death, 2013

Upstairs, Madisson “Madi” Mohler sits in her new room, the very one that belonged to her big sister, Brooklynn. She only moved in a few months ago and around her are reminders of who she lost.

Barbies Brooklynn once collected line shelves above the bed, right near her dangling dream catcher. There’s the poster of puppies the animal-lover wouldn’t leave Target without owning. Butterflies, wind chimes and pompoms are strung across the ceiling.

And by the window is Brooklynn’s bulletin board, crowded with a collection of inspirational sayings she jotted down not long before she died.

“Add life to your days, not days to your life,” reads one. “Don’t give up,” says another. “I’d rather have a life of ‘oh wells’ than a life of ‘what ifs,’” reads a third.

These notes, most now faded by the sun and time, turned out to be a gift to her family. It was one they desperately needed because nothing could have prepared them for what took Brooklynn away.

Three years ago, Brooklynn was at her best friend’s house when her friend began messing with an unsecured 9 mm Glock. As Brooklynn walked away, a response she’d been taught, the gun fired. A bullet tore through her spine before puncturing her lung and then her heart. She died soon after. She had just turned 13.

“I looked up to her like she was a hero,” says Madi, who was only 9 at the time.

Brooklynn often played teacher in their Henderson, Nevada, home, and Madi was happy to be her student. She remembers being schooled on vowels and similes. Her big sister liked Carrie Underwood, so she did, too. They competed with each other in the Wii game “Just Dance.” Both gymnasts, Brooklynn insisted Madi do conditioning exercises during TV commercials. Madi did as she was told, launching into quick workouts or dropping into splits.

Madi was with her dad and one of his friends when they went to pick up Brooklynn from her friend’s house. She knew something was wrong; her father went inside, which was strange, and then an ambulance pulled up. A police officer arrived and told her dad’s friend to take Madi away. She thought someone had broken an arm or something.

A while later, her aunt took Madi to the hospital.

“I remember going into the lobby and my dad had to tell me and [my brother] what happened,” Madi says. “My mom was in a separate room called ‘the quiet room’ and my aunt ran in there and I just heard crying and screaming.”

The house then filled with family and tears. She was overwhelmed and not sure what to make of it all. An uncle bought Madi a cake pop maker to keep her occupied. When she ran out of ingredients, someone screamed to go buy her more. So she dutifully kept making those cake pops. Madi, now 13, laughs, saying she made “too many to remember.”

Too old to be distracted by cake pops was Levi, the only son. He was 16. Now 19 and in college, he still struggles with blaming himself.

“I always felt it was my job to keep her safe. And when that happened, I just felt destroyed,” he says. “I could’ve prevented it.”

When some boys were picking on Brooklynn in middle school, Levi showed up to escort her home and scare them off. When she once wanted to walk to Taco Bell with a friend while wearing a swimsuit, he was quick to shut that idea down. She never got in trouble, and he jokes that he “set the example of what not to do.”

More on Guns in America

The other gun lobby

They are, sadly, growing in number: Americans devastated by gun violence. The connections they’ve forged are strong. But can they defeat the NRA?The loneliest club

They are survivors of gun violence. But they also share a conviction: to use the worst days of their lives to make America a safer place.The massacre that didn’t happen

The case against 11th grader John LaDue looked like a slam dunk. Bomb-making material in a storage locker. A confession. An arsenal in his bedroom. But the case would turn out to be anything but simple. Can cities stop the bloodshed?

Savannah, Georgia, and Richmond, California: Two cities on opposite sides of the country, each with a history of homicides and different approaches to ending the violence. See what’s working and what isn’t in this two-part series.The story in charts and graphs

Guns per capita by country. Background checks by month. Deaths by terrorism vs. gun violence. See the visual story of gun violence in America.

Levi didn’t like Brooklynn’s friend, the one who accidentally fired the gun. From the moment he met her, he says, there was something about that girl he didn’t trust. Maybe, instead of going to her house after school that day, he could have insisted Brooklynn come home with him?

When he heard she’d been shot, he thought to himself, “Oh, we’re going to joke about this 10 years from now.” On the way to the hospital, he imagined showing his kids Aunt Brooklynn’s little scar from that crazy time she took a bullet.

But after his trot into the hospital turned into a run and he rounded the corner to see his father, he backed against a wall and sunk to the floor. The last time Levi had seen his dad cry like this was after they put down their German shepherd, Baron.

Back home, he remembers their mother holing up in her bedroom as people streamed in and out to see her. He retreated to his own room, where the thought of food or drink made him sick.

When he emerged, he says he felt like he had to be strong for his mom and Madi. Sometimes he’d just hold his mom as she wept, fighting to hold back his own tears.

“I tried to be strong for her,” he says, now crying. “It was really hard.”

With his father, he says, he was able to “go out back and kind of hug it out.”

Jacob Mohler says he’d be lying if he said he was the best father he could be in the first six months or even year after Brooklynn died.

He had walked into the house where Brooklynn was shot minutes after it happened. He held her as she struggled to breathe.

“It was a blessing and a curse,” he says. “I got to be with my baby in her darkest hour, but the things I see when I close my eyes – I wouldn’t wish on anybody.”

Today, he likes to say, “Deal with your grief or your grief will deal with you.”

It’s a philosophy shared by his wife, Darchel, who knows too well what it’s like to lose a sibling. Her younger sister Tessa died in a car wreck at 17. But Darchel not only lost her, she also lost her mother to grief.

“I thought at the time that would be the worst thing I’d ever have to go through,” says Darchel, who was 26 and pregnant with Madi at the time. “I can empathize with my children. … And I understand my mother more now.”

She was determined to be present for her kids, even if emotionally she had checked out, and to make this house a safe space to cry and feel.

Madi goes to a grief group with other kids her age. The first day they met, they wrote down what made them mad and then set those words on fire – before making s’mores. They do crafts “dedicated to our lost one,” she explains. She’s made a Valentine’s card for Brooklynn, decorated candy canes and made a new dream catcher.

Down the hall, in her mother’s office, there’s a painting by Madi. It features two girls, side-by-side, with tears running down their cheeks. Atop one are the words, “I miss you Sissy.” The other girl, almost identical, wears angel’s wings.

Sometimes relatives will say things like, “You’ll grow up to be just like Brooklynn,” Madi says. And while she’d like to be like her sister, she says, “I’m not like her. I want to be my own self.”

Levi balked at the idea of counseling in the beginning. He was sure he could handle it on his own. He played on the football and lacrosse teams and channeled his feelings onto the field.

He’d look for big hits, he says. He got concussions but never told anyone. He played a whole football season with a broken wrist. Even on his violin, an instrument Brooklynn took up so she could be like him, he poured his heart into his music, using that same broken wrist.

Today, he’s not ashamed to see a counselor. He’s even thinking he might become one himself. When he needs a good cry, he often turns to music. Cole Swindell’s, “You Should Be Here,” helps bring up lots of stuff, he says. Sometimes he’ll even listen to Brooklynn’s playlist, including her “stupid little boy band artists” – the very music that used to make him scream, “Turn that off!” when he heard it through the wall between their bedrooms.

About a year after her death, the family established the Brooklynn Mae Mohler Foundation. Its mission is to push for responsible gun ownership and encourage parents to ask other parents if they have unsecured firearms in their homes. In Brooklynn’s name, they host runs and set up tables at community events to raise awareness. It’s a mission, Levi says, that helped bring the family together, offered them purpose and allowed them to really talk about Brooklynn.

“It was probably the best thing that we could’ve done,” he says.

The scars, however, still run deep.

Darchel, who was already plenty overprotective before Brooklynn died, is an even more nervous mother. Just ask Madi.

“I don’t have as much freedom as I would like,” she says. “I can’t really go over to other friends’ houses because of my mother’s anxiety. But it’s cool because my friends get to come over here, and personally I think it’s more fun over here. I feel safe in my own house.”

And Levi, who never suffered from anxiety before, says he now suffers from it “like crazy.” A glass half-full guy before, he’s now prone to fixating on worst-case scenarios.

His worrying, he thinks, helped drive a girlfriend away. He needed to know where she was all the time and that she was safe.

“She didn’t quite understand it and I didn’t expect her to,” he says, as he wipes away new tears. “I did love her, and it would kill me if something happened to her. … It would kill me to lose someone again.”

He understands his mother’s overprotectiveness. When other friends were getting their driver’s licenses, he held off until he was 18. His mother couldn’t handle the thought of him driving off.

“I’ll take the bus. It’s OK. Don’t worry,” he remembers saying. “I’ll get my license when you’re ready for me to.”

Such milestones make him think of Brooklynn. Moments that should be joyous carry a sting.

“She never fell in love. She never got her driver’s license. She didn’t graduate high school,” he says. “She never got to go play a varsity sport, never got to go to prom.”

When his thoughts turn to Madi, though, his words carry a different weight. Levi says he and his younger sister grew distant after Brooklynn was gone.

“I don’t know if that’s normal,” he says, “but this is what happened.”

Madi has no illusions about this either.

“There’s such a big age difference. We don’t really talk a whole lot,” Madi says. “But I kind of want that to change because I don’t like not talking to my brother.”

With Brooklynn, they had a bridge that bound them. She was the consummate middle child. She was, as her parents describe, the hub to their family wheel.

Now, three years after a bullet took her away, her two surviving siblings must find their own connection.

– Jessica Ravitz, CNN

‘He was my role model’

A gang prank and a brother gone, 2006

Tre Bosley holds a blue candle and walks in silence with more than 100 others protesting the violence that plagues Chicago’s South Side.

Tre is an impressive young man, a high school basketball star with a stellar GPA who leads an anti-violence youth group.

Beneath his bright smile and optimistic outlook is a teen who knows the despair of the city’s mounting death toll. Tre was just 8 when his older brother, Terrell was killed in a gang prank a decade ago.

Terrell was 18, a motivated young man who shunned the gang life for church choir.

Pinned to Tre’s chest is a button bearing his brother’s image. A reminder of why he keeps fighting.

“He was my role model – truly a role model,” Tre says.

Saving lives has become Tre’s mission. He has known about a dozen people who’ve been killed, from his brother to a cousin to a special needs teacher.

Tre takes his message – and his button – everywhere he travels. Earlier this year, he was far from his South Side neighborhood, standing face-to-face with President Barack Obama during a town hall on gun control.

“My question to you is: What is your advice to those growing up surrounded by poverty and gun violence?” Tre asked at the end of the event.

Obama looked at him. “When I see you, I think about my own youth because I wasn’t that different from you – probably not as articulate and maybe more of a goof-off, but the main difference was I lived in a more forgiving environment.”

The President told Tre not to give up hope, to keep being a role model, to work hard, to strive for great things through education. “But what I also want to say to you is that you’re really important to the future of this country.”

The President’s words touched Tre in unexpected ways. “He kinda told me that I’m the future – not only me, but the youth are the future of this country,” he says. “It really inspired me.”

Before his brother was killed, Tre used to dream big. Like of becoming the president of the country or heading up a major company. But in the years after, he says, “I kind of diminished my goals.”

It was more about surviving day to day. There were few African-American role models in his neighborhood.

His mother became more protective. He wasn’t allowed to leave his block. She drove him to school. A nearby basketball court was off limits. “She doesn’t let us walk there or go play or nothing,” he says. “We really stay on that one portion of the block all the time.” Even there, playing basketball in an alley, he can hear gunshots.

Tre remembers everything “very clearly, actually” from April 4, 2006. How could he ever forget that day?

He was studying math with his father in the front room of their home. His mother took a phone call, then screamed: “Terrell’s been shot!”

His books fell to the floor and everyone ran from the home. They hopped in the car and rushed to Terrell’s side.

Terrell sang in a community choir and played the bass at various churches around Chicago. He was helping a friend take drums into a church when shots rang out. He was hit once in the shoulder. A friend was hit multiple times, but survived.

The family was later told that one gang member had played a prank on another, saying Terrell was a member of a rival gang. “When he shot them, the other guy said, ‘I was just kidding,’” mother Pam Bosley says. “You mean to tell me my son is gone because of some joke?!”

Tre watched his brother get loaded into an ambulance and rushed to the hospital, sirens blaring. His mom was crying, so were he and his other brother, Terrez, then 13. “My mom was telling us to pray – just keep praying, make sure that you keep praying.”

At the hospital, he and Terrez watched from a waiting area as a doctor told their parents Terrell had died. The room filled with wails and tears. Their dad “came and told us, and we started crying.”

Tre thought about the time Terrell beat him in checkers. He had promised he’d beat his older brother one day. “Just knowing I’d never be able to do that – at first, it hurt.

“At that moment in the hospital, I didn’t truly know what was going on. It just felt like a dream.”

Terrell had been his idol. He kept the talkative, overconfident young Tre grounded. Told him not to be so boisterous with his smack-talk.

One of Tre’s favorite memories was sitting with Terrell in his car listening to music. Tre didn’t have much rhythm, so Terrell tried to demonstrate: “He was like, ‘Look you should bob your head like this. Not like that! It’s got to be on the beat.”

Tre laughs. All these years later, that memory brings a smile. “I’ll never forget the moment he taught me how to bob my head.”

Other memories race back, like when they’d drive together to school. “We used to pray in the car on my way to school. We’d pray that no one else would get harmed. We prayed every day to keep our family safe and that no one gets shot and killed in our family.

“That was before he got killed. Then, I started to pray by myself.”

Terrell was killed just before Easter. For years after, the family stopped celebrating holidays. They’d stay in a hotel for Christmas because the grief at home was too overbearing. Terrell had loved Christmas; he’d go over the top with decorating the house, inside and out.

Only in the last couple of years has the family been able to celebrate Christmas at home. Tre had begged his mother to allow them. “We just started putting a tree back up,” he says.

For now, it’s the only decoration.

“On Christmas, when you’re getting your gifts, you just know that there’s supposed to be somebody else getting their gifts,” he says. “I always feel like something is missing. You never feel like the holidays are complete.”

His mom has filled some of the void of Terrell’s absence – thrusting him into activism and making sure he kept up with his studies. Now 18, Tre graduated with a 4.2 GPA and will attend college on scholarship.

Tre also credits his pastor, the Rev. Michael Pfleger, the fiery priest of Saint Sabina who has been a community activist for decades.

Pfleger says all too often parents turn to alcohol or drugs after losing a child – and surviving siblings get lost amid the grief. He praises Tre’s parents for keeping him on the right path, and he says Tre’s perseverance and positive attitude played a major part in shaping who he is today.

“He’s got a great blend of a strength and a sensitivity that I’ve always admired,” Pfleger says.

It would have been “easy for him to become either angry or bitter after losing his brother, or to turn to the streets or live in fear after that. Instead, he made a decision to join with his parents … and put his emotional pain, hurt and trauma into trying to be a voice for other young people.”

Tre serves as the president of The BRAVE Youth Leaders, an anti-violence organization that goes into the community, delivering a message of peace. They also help with mentoring and voter registration. BRAVE stands for Bold Resistance Against Violence Everywhere.

He likes the Black Lives Matter movement and appreciates its efforts, but he wishes it would “address black on black crime as much as they do police brutality.”

“I mean: How can they expect to give us justice for those killings when we don’t even expect justice for our own killings?”

His brother’s killer has not been caught.

Still, meeting Obama has inspired Tre to fight even harder for change and for equality for all.

“Knowing that your role model is gone and I’m still trying to follow his footsteps,” Tre says, “I know (my brother) would be proud of me for what I did and what I said.”

He pauses. “I think that’s my response to everything that happened to me after my brother. My response was I need to go out and make a change so that other people won’t go through what I went through.”

Terrell would be proud in other ways, too. On what would’ve been Terrell’s 28th birthday, Tre played in a high school basketball game. Under his jersey, he wore a T-shirt commemorating his brother’s life.

On the court, Tre couldn’t be stopped. He caught fire, hitting five 3-pointers. “I know I played well because he was looking down, and he helped me out that game.”

Again, Tre lights up.

– Wayne Drash, CNN