Editor’s Note: Peniel Joseph is the Barbara Jordan Chair in Political Values and Ethics and the Founding Director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is also a professor of history. He is the author of several books, most recently “Stokely: A Life.” The views expressed here are his.

Story highlights

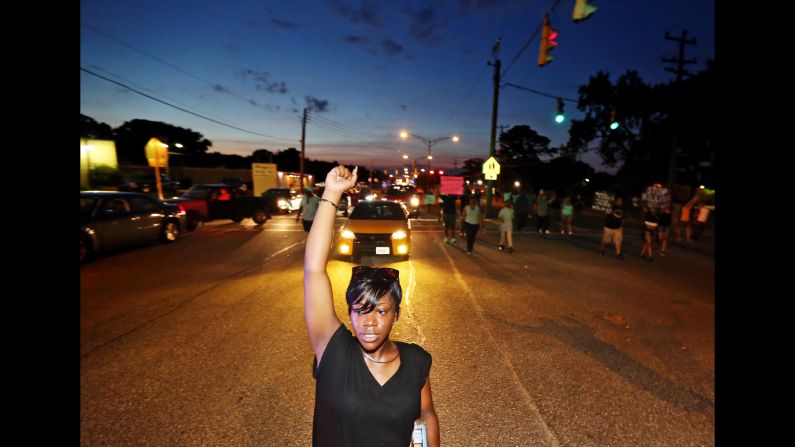

Black Lives Matter -- not anti-police and not responsible for violence against police.

Inflammatory and ill-informed critics have turned the focus away from the race problem in America

The tragic deaths of eight law enforcement officers from Dallas and Louisiana have inspired rhetoric blaming social justice advocates—specifically Black Lives Matter demonstrators—for fanning the flames of anti-police sentiment to a boiling point that makes them virtual co-conspirators with the two alleged assassins themselves.

This rhetoric dangerously obscures work done over the last two years by Black Lives Matter activists to highlight the hierarchy of life and death in America, one demarcated by stark divisions across race, class, gender, and sexual orientation.

Black Lives Matter activists have never been anti-police, anti-white, or anti-government. The young women and men who comprise a close network of community groups organizing under this banner — as well as the tens of thousands of people who have demonstrated as fellow travelers in this movement — have been vocal critics of structural and institutional oppression that flourishes in some of America’s most disadvantaged and invisible cities like Ferguson, Missouri – and Dallas, Memphis, and Washington, D.C., among others.

But now, inflammatory and ill-informed critics have turned the national conversation about race, policing, and the criminal justice system – that just two weeks ago finally appeared ready to take place in the aftermath of the police shooting deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile – into an historic tipping point. Conservatives dishonor the truth as well as their own political cause by scapegoating Black Lives Matter activists for creating — rather than merely identifying and speaking out against — the atmosphere of violence that led to the deaths of police.

No one can or should try to justify the senseless and apparently racially motivated killings — although at least one Baton Rouge officer was African American — of eight officers in the past eleven days. Law enforcement forms one of the pillars of civil society, charged with serving and protecting the rights of fellow citizens and burdened with the responsibility to use lethal force in doing so.

Adding insult to national injury, presumptive Republic presidential nominee Donald Trump, in Cleveland to attend a Republican National Convention that might be the most divisive in American history, promises to take the nation back to the future via a remake of Richard Nixon’s “law and order” rhetoric. The bombastic Trump makes Nixon’s naked appeal to America’s worst racial impulses seem elegant and subtle by comparison.

As we can see on display in Cleveland, the violent deaths of black people at the hands of the police — more than 120 already this year alone — are once again ignored in favor of a frightening new (old) narrative that reframes our national crisis of race and democracy as being rooted in black criminality and a disrespect for the law aided and abetted by radical black activists.

Trump’s reboot of Nixon’s divisive approach in 1968 masks the real national crisis: Renewed patterns of neighborhood and public school segregation, reduced social and municipal services, poor access to mental, physical, child, and elder care, and high rates of unemployment. These trends turned many poor black communities into some of America’s most vulnerable places. Indeed, as the Justice Department documented in Ferguson, local municipalities have used racial profiling, arrests, and fines as a gruesome financial scheme to balance city budgets on the backs of the poor.

On this score, and by underlining the urgency of these crises, Black Lives Matter activists have cast a strobe light on the criminal justice system as a pervasively unequal tool that not only marginalizes black people, but also exploits and profits from their misery in ways that did not exist even a half century ago.

Speaking to reporters in the immediate aftermath of Baton Rouge, President Obama issued words of caution. “We don’t need inflammatory rhetoric. We don’t need careless accusations thrown around to score political points or to advance an agenda.”

I fervently agree with the president, but would add these points of emphasis.

First, the search for justice is never inflammatory, since peace is what justice looks like in public. Black Lives Matter activists and their allies continue to organize peaceful demonstrations in a quest for black equality that holds the key to racial and economic progress as we move forward.

Join us on Facebook.com/CNNOpinion.

Second, all Americans should be united in advancing the cause of social justice that remains the bedrock of faith in our democratic system. That agenda is rooted in a belief exemplified by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s observation that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Dr. King’s “fierce urgency of now,” in our own time, is the courage and ability to speak truth to power.

Black Lives Matter did not invent racial hatred or violence, but have instead mounted a human rights movement bold enough to articulate unspeakable, unspoken truths about a national culture of violence, division, and racial oppression.

Now is the time to get to the root of America’s culture of violence and racism in order to achieve national consensus on eradicating institutional racism, ending economic injustice, and infusing our politics with a culture of civility, respect, and honor.

Blaming social justice activists brings America no closer to the beloved community that Dr. King gave his life for. Neither will electing demagogic leaders who gleefully exploit human tragedy in order to push a divisive agenda that brings us no closer to solving race relations in 2016 than it did in 1968.