Editor’s Note: Robert Klitzman is a professor of psychiatry and director of the Masters of Bioethics Program at Columbia University. He is author of “The Ethics Police?: The Struggle to Make Human Research Safe.” The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

Robert Klitzman: Minneapolis news report: Prince died of opioid overdose. Reports on his medical treatment suggest VIP Syndrome

By wanting to accommodate celebrities, some doctors fail to provide proper tests, treatments, Klitzman says

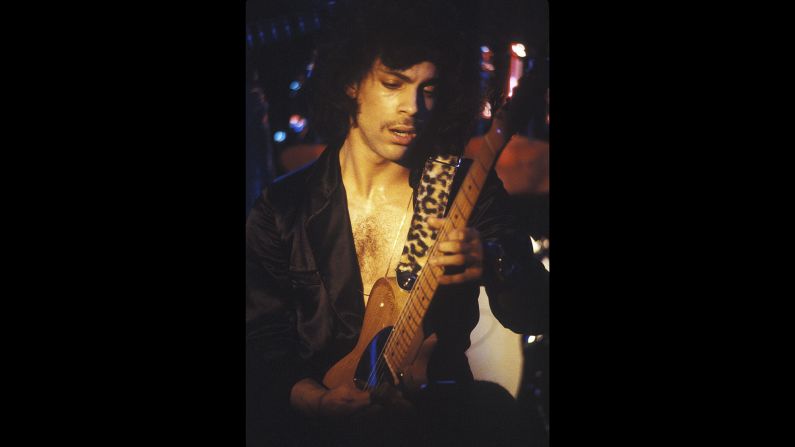

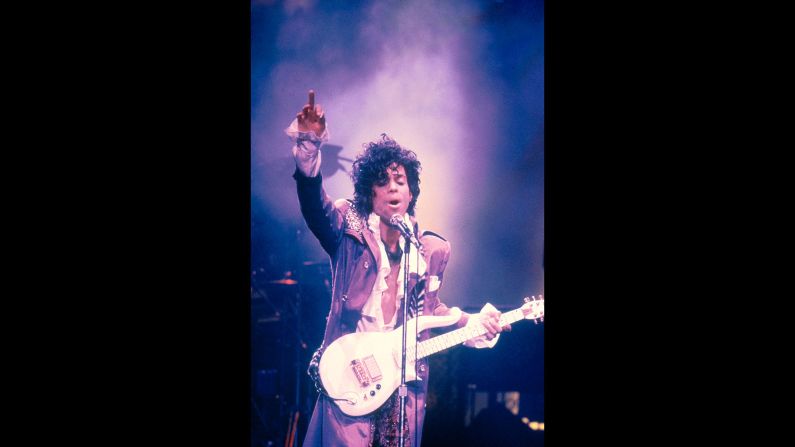

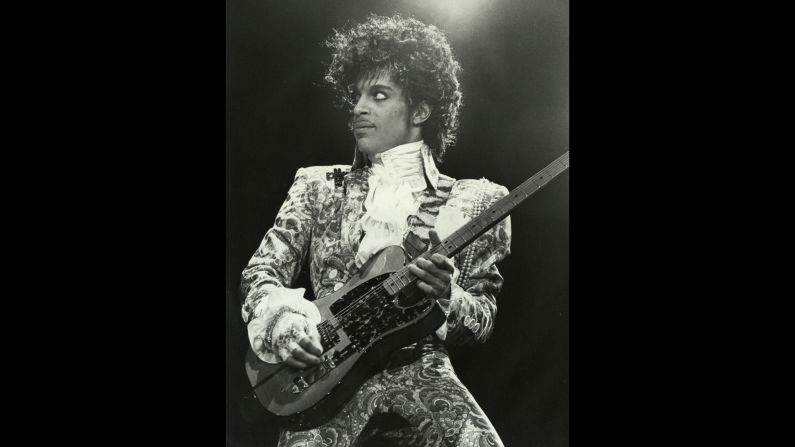

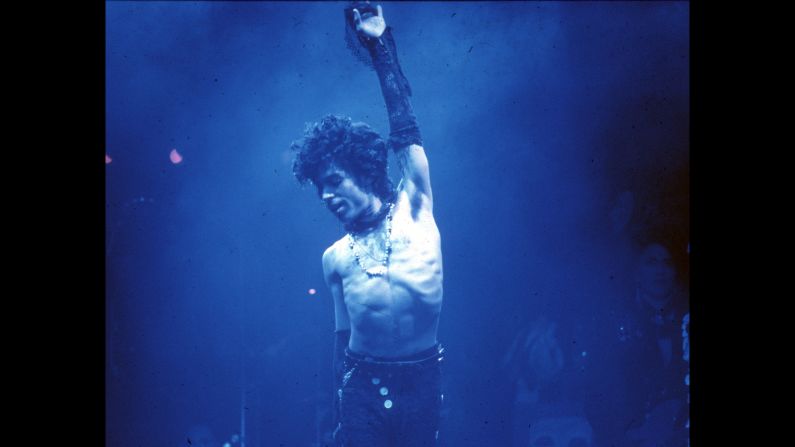

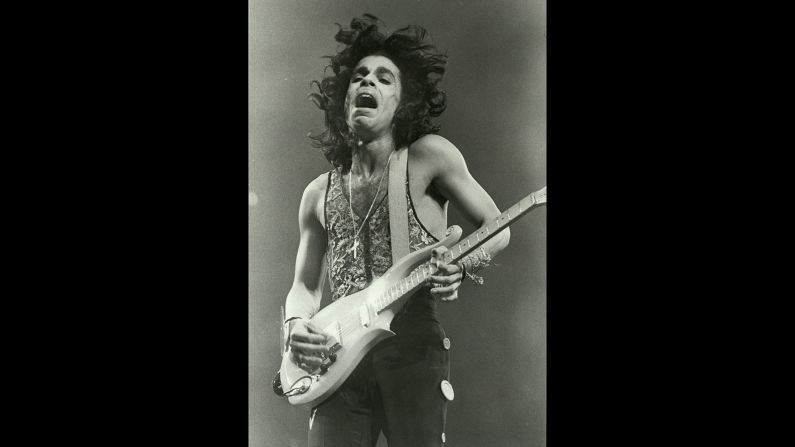

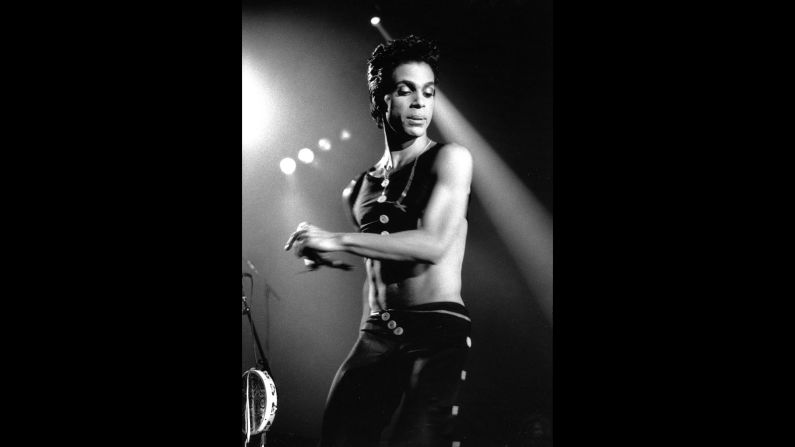

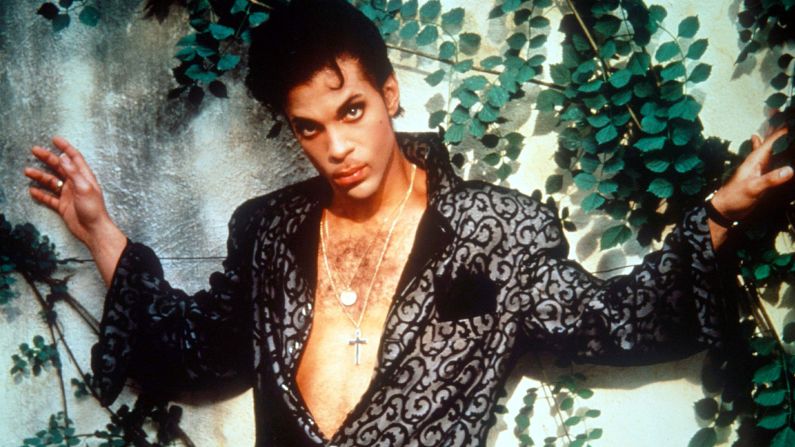

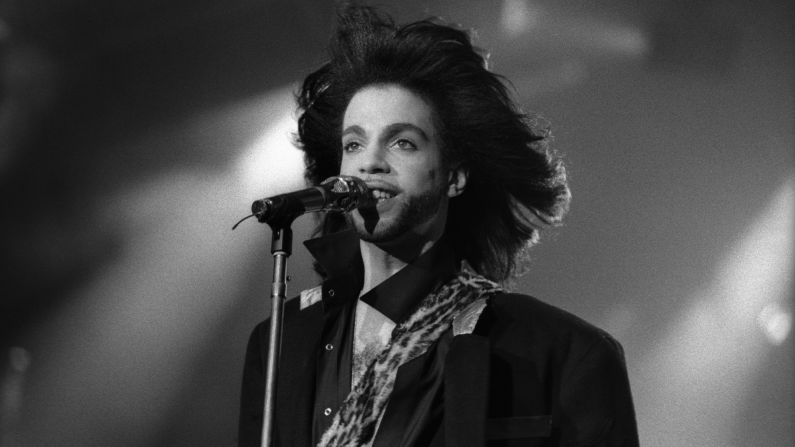

A deadly ailment killed Michael Jackson and Joan Rivers – and may have figured in the death of the rock star, Prince.

It’s called “VIP syndrome.”

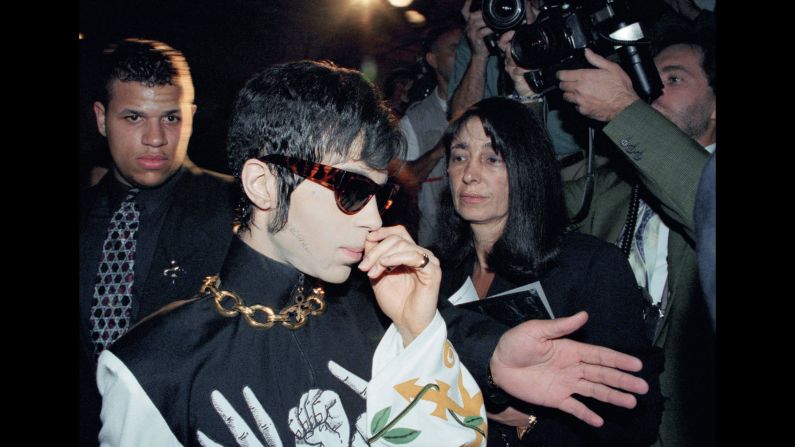

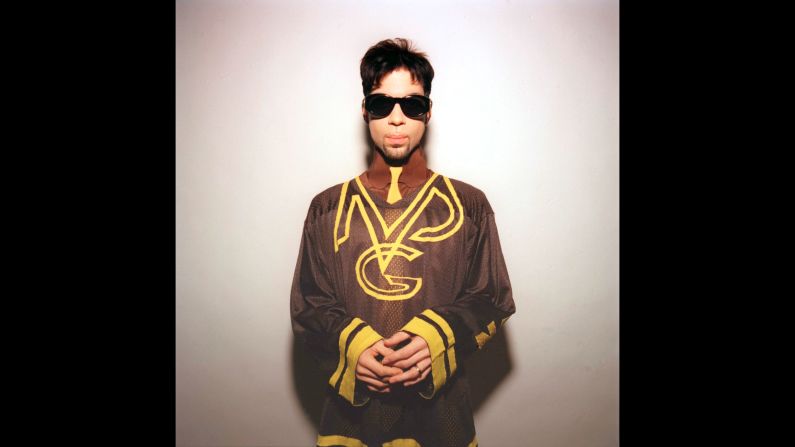

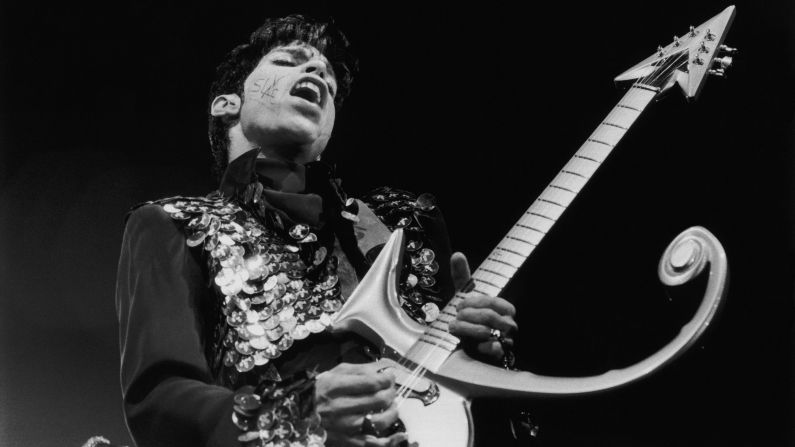

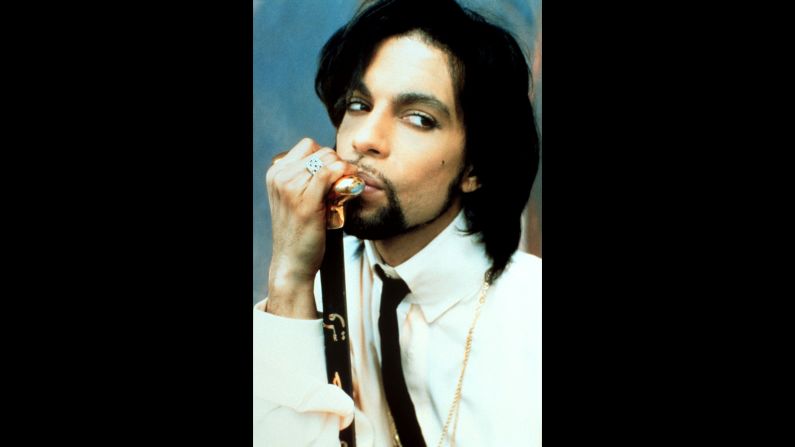

We still don’t know all the details of Prince’s death – or the medical treatment that preceded it – but on Thursday, the Minneapolis Star Tribune reported that Prince died of an opioid overdose, citing a source familiar with the investigation into the singer’s death.

And earlier news accounts of the few weeks leading up to the discovery of his body in an elevator at Paisley Park describe a period of medical care and attempted medical care – by both doctors and non-doctors – that raises many troubling questions, including whether VIP syndrome occurred.

First described in 1964, by a psychiatrist, Walter Weintraub, VIP syndrome occurs when doctors treat an “important” patient as “special,” making exceptions to standard procedures. The doctors seek to accommodate these patients, foregoing appropriate tests and safety measures because the VIP might find these inconvenient.

Many celebrities are used to being treated as special, not having to wait in line, and getting around bureaucratic obstacles the rest of us face. They may actively seek special treatment in their health care, too. For some, this can produce successful outcomes – the best care money can buy.

For others the result can be substandard care. Some doctors feel awkward performing tests on VIP patients that might be uncomfortable, take too much time or seem too personal – an internal exam, for instance – and as a result they miss problems.

A doctor I know once treated the son of one of the wealthiest men in the world and a household name. The man had hired five specialists from around the country to treat his son. But these specialists couldn’t agree on what to do.

In the end, nothing got done. The son died. If one doctor had been in charge, as occurs with “ordinary” patients, the son may well have gotten more and timelier treatment, and fared better.

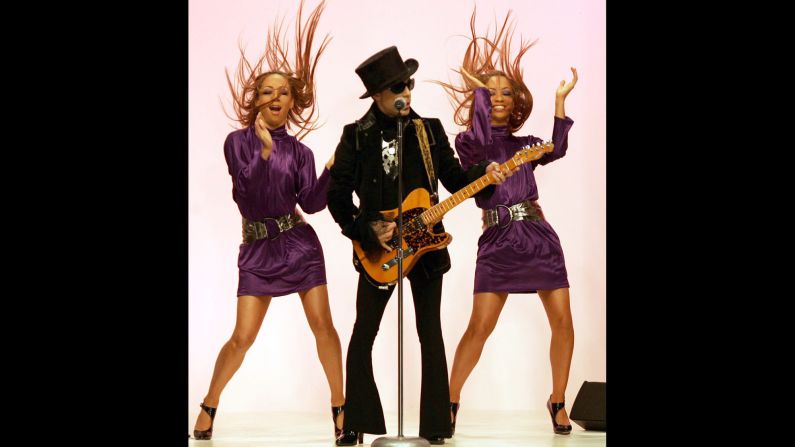

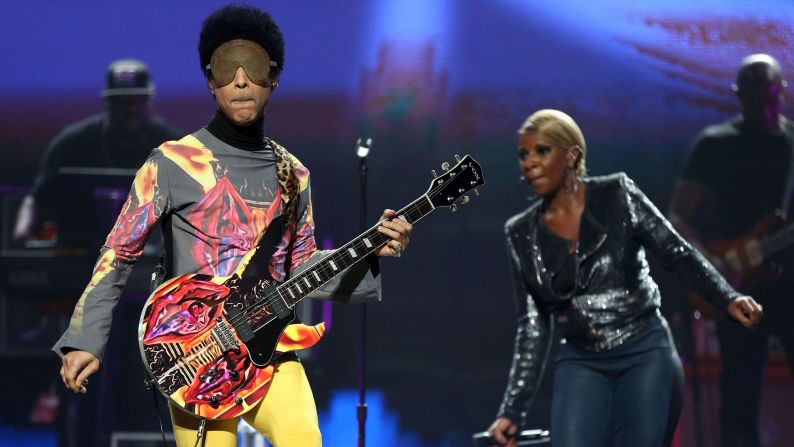

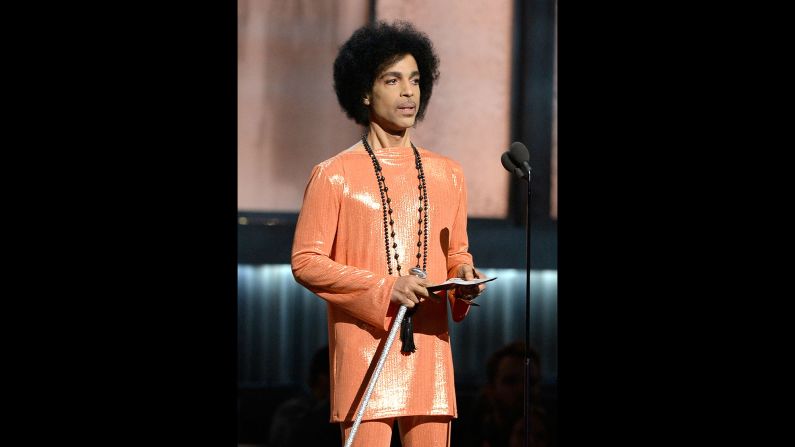

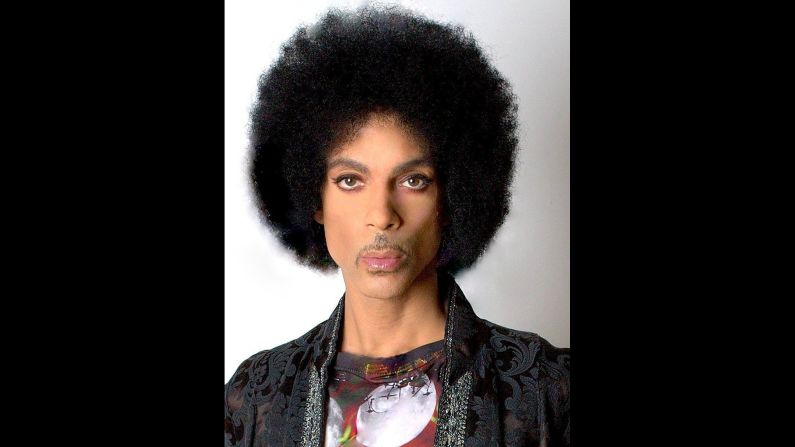

We worship celebrities like gods. They appear on our smartphone screens, our TVs and our computers, and loom high above us in movie theaters, larger than life, seemingly more beautiful and glamorous than the rest of us. For good or bad, doctors are humans like everyone else, wowed by celebrities, and don’t always proceed as they should when treating them.

Dr. Conrad Murray, for instance, gave Michael Jackson intravenous propofol at home; it’s a powerful anesthetic, normally administered only under strict supervision in a hospital. Murray was convicted of involuntary manslaughter.

Joan Rivers’ doctors, too, violated standard protocols. One even photographed Rivers on the operating table, using his cellphone – wholly unprofessional behavior. This month, five doctors and the clinic where they had been performing a routine procedure on Rivers when she went into cardiac arrest accepted responsibility for her death, settling a malpractice lawsuit.

I’ve heard doctors “drop” the names of their celebrity patients to impress colleagues. I’ve learned of the psychiatric treatment of various A-listers that the media has not reported. I have treated VIP patients, and I indeed did feel intimidated, awed and privileged. It is not always easy for medical professionals to prevent these feelings from arising or impeding our work. But we need to do so.

And it’s not only celebrities that can be afflicted by VIP syndrome. Others, including professional colleagues – such as physicians getting treatment where they work, and wealthy people who, hospitals believe, may donate money – can end up with it, too. In such cases, physicians may be motivated not solely by the patient’s best interests, but by other concerns: money, glamor, friendship, social hierarchy, prestige.

In the case of Prince, we do know (according to a search warrant) that he was prescribed medication by Dr. Michael Todd Schulenberg, a local doctor who worked in primary care and obstetrics at a Minnesota health care center but left the job a few weeks after the musician’s death.

A few days before Prince’s death, the rock star’s representatives contacted Dr. Howard Kornfeld, a California addiction specialist, who sent his son, Andrew, a non-physician, to see Prince. Andrew Kornfeld told investigators he brought buprenorphine – which Dr. Kornfeld has advocated for treatment of narcotic addiction – to give to “a Minnesota physician.” Instead, Andrew Kornfeld was one of the three individuals who found Prince dead.

Apparently, Dr. Kornfeld never examined Prince, and is not licensed by Minnesota to practice medicine in that state. And if Dr. Schulenberg was the physician to whom Andrew Kornfeld was delivering the buprenorphine, that’s a problem, too: He is not registered in the state to prescribe buprenorphine.

Prince had painful hip injuries from jumping onstage but is not known to have had any other major diagnoses, although he was apparently treated for an unspecified illness in 2014 or 2015 at a local medical center.

Many questions remain. If he did indeed die from an opioid overdose, questions will arise that medical records will hopefully answer. What was he taking and how much, who prescribed the drugs, and over how long?

And had Prince seen a psychiatrist, particularly one who specializes in addiction?

Was VIP syndrome involved? Alas, it appears a distinct possibility.

Patients should receive treatment from a physician who examines them, and has expertise in the interventions he or she is prescribing. Unfortunately, mental illness, including substance abuse, is often treated not by psychiatrists, who have specific training in caring for these ailments, but by others.

Half of patients with depression, for instance, never receive any treatment. And about 80% of prescriptions for antidepressants are written not by psychiatrists but rather by other doctors who rarely have any specialized training in caring for mental health problems and thus often over- or under-treat. VIP syndrome can further diminish the likelihood of getting appropriate treatment and optimal care.

That is at least partly due to the stigma surrounding mental health problems, including substance abuse. Prince and his representatives may well have hidden his opiate use: A week before the rock star’s death, when his plane had to make an emergency landing because of “an unconscious patient,” his staff said he had the flu, though some reports suggest narcotics were involved.

Providers who are not psychiatrists need more and better training in how to treat substance abuse and other psychiatric disorders; and all providers – medical students as well as practicing physicians – need more education about the hazards of VIP syndrome. Celebrities and their handlers need to be aware of the pitfalls of such “special” treatment as well.

Finally, we all need to stigmatize substance abuse less. Doing so would make it easier for countless individuals to receive appropriate care – whether they are famous or not.

Join us on Facebook.com/CNNOpinion.

Read CNNOpinion’s new Flipboard magazine.

Robert Klitzman is a professor of psychiatry and director of the Masters of Bioethics Program at Columbia University. He is author of “The Ethics Police?: The Struggle to Make Human Research Safe.” The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.