Story highlights

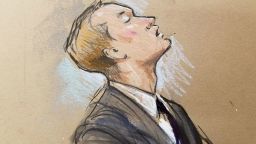

Edward Nero sobbed upon hearing not guilty verdict in Freddie Gray case

Nero found not guilty of all charges in Gray case, including 2nd-degree intentional assault

Gray's April 19, 2015, death became a symbol of the black community's distrust of police

Perhaps no one found Baltimore police Officer Edward Nero’s not-guilty verdict Monday so surprising.

But to hear the families of Nero and of Freddie Gray, the young black man who Nero was accused of assaulting, both lauding the judge who handed down the decision? Surely no one saw that coming.

While Nero released a statement saying he and his family were “elated” with the ruling, Gray family attorney Billy Murphy, too, applauded the decision, saying, “You can’t convict people unless you know the evidence,” and that Judge Barry Williams had followed the law as he saw it.

After a bench trial, Williams found Nero not guilty of all charges in connection with Gray’s death last year.

Williams took 20 minutes to read the decision to a packed courtroom and near-capacity overflow room. Wearing a dark, three-piece suit and tie, Nero nodded as Williams said there was no evidence to support each individual charge and tilted his head back in relief after the judge read the verdict. He then put his head down and sobbed.

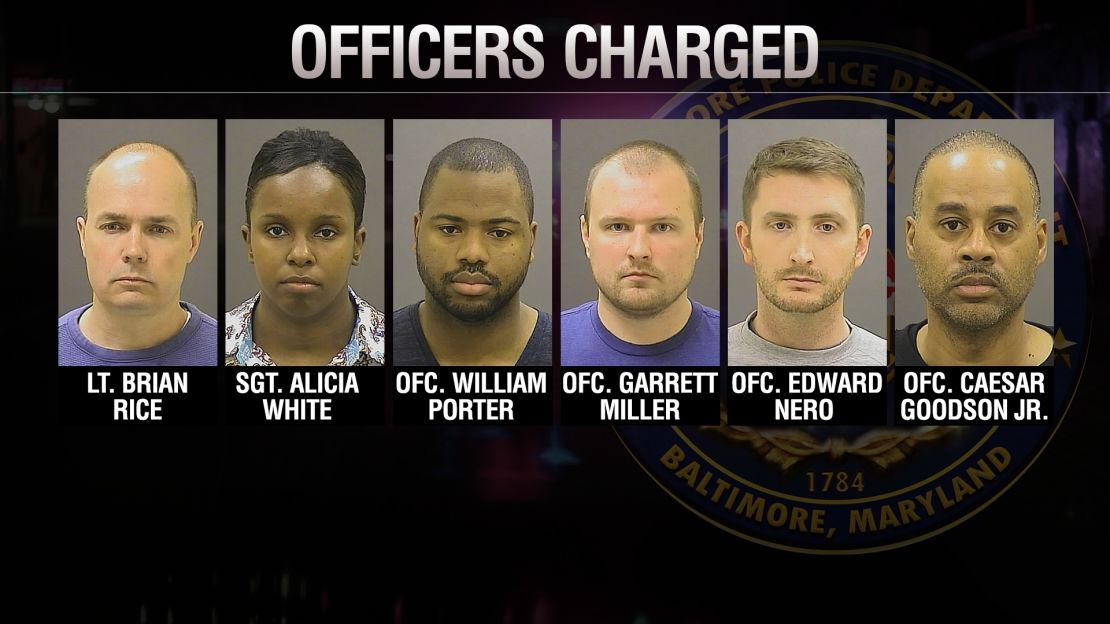

Nero, one of six officers charged and the second to be tried in the Gray case, was accused of second-degree intentional assault, two counts of misconduct in office and reckless endangerment.

Nero was one of three bike officers involved in the initial police encounter with Gray that day in April 2015.

About a dozen or so protesters surrounded and chanted at Nero’s brother as he left the court. Sheriff’s deputies escorted him into a parking garage.

The verdict, which drew mostly outrage on social media but praise from police and the Gray family attorney, brings perhaps only a sliver of resolution to a city that seethed with unrest over the death last year of the 25-year-old prisoner. Four more officers’ trials are slated to take place.

Praise on both ends

Lt. Gene Ryan, president of Fraternal Order of Police Lodge No. 3, said in a statement that Nero was pleased with the verdict but concerned that five other officers, Nero’s “good friends, must continue to fight these baseless accusations.”

Ryan accused State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby of leveling charges not as the product of a “meaningful investigation” but as a response to riots in the city after Gray’s death. in the process, she “destroyed six lives,” Ryan said, as well as the relationship between the Baltimore Police Department and her office.

“None of these Officers did anything wrong,” Ryan said in his statement. “Officer Nero is relieved that for him, this nightmare is nearing an end. Being falsely charged with a crime, and being prosecuted for reasons that have nothing to do with justice, is a horror that no person should ever have to endure.”

A statement from Nero’s lawyer echoed some of the same points and also used the word “nightmare” to describe Nero’s prosecution.

“The State’s Attorney for Baltimore City rushed to charge him, as well as the other five officers, completely disregarding the facts of the case and the applicable law. Officer Nero is appreciative of the reasoned judgment that Judge Barry Williams applied in his ruling,” said the statement from defense attorney Marc Zayon.

Nero’s father, Edward Nero Sr., told CNN affiliate WSVN that the verdict was a victory not only for his son but for all police.

“I believe it allowed the police officers to do their job, and if he was found guilty, I believe many officers would have been hesitant to do the right thing when it came time to dealing with crime because they would be afraid to be prosecuted,” he told the station.

A police statement said Nero will remain on administrative capacity during the investigations, which won’t be completed until the last officer’s trial ends because the officers may be called as witnesses in their co-defendants’ cases.

Gray family attorney Murphy applauded Williams, saying that, as an African-American judge, “he did not bend to that pressure” from the black community, many of whom wanted to see Nero convicted as an emotional response to Gray’s death. The family might not be pleased with the verdict, he said, but they respect the rule of law.

“You couldn’t ask for a more fair-minded judge than Barry Williams,” Murphy said. “I hope (the ruling is) going to be received with equanimity.”

On a wider scale, posts on social media expressed mostly disdain for the verdict, with a smattering of approval. While one user wrote that he felt “justice prevailed in the face of Obama’s lawless regime,” others, including writer and activist Shaun King, felt the verdict represented anything but.

Writing on wall?

Williams’ line of questioning during trial last week may have been a harbinger of the final outcome. He challenged prosecutors’ claim that the takedown and subsequent arrest of Gray without probable cause amounted to a criminal assault.

The verdict comes more than a year after Gray’s death on April 19, 2015, became a symbol of the black community’s distrust of police and triggered days of violent protests. Gray was black. Three of the officers charged are white, three are black.

Closing arguments concluded Thursday.

Community leaders and elected officials have appealed for calm. The citizens of Baltimore had demanded justice, they said, and that process is playing itself out.

“Whatever may be Judge Barry Williams’ decision with respect to Officer Nero’s role in the death of Mr. Freddie Gray, that verdict will have as much legitimacy as our society and our justice system can provide,” Maryland Congressman Elijah Cummings said last week.

“I join the mothers, the fathers, the children … of Baltimore asking not only for peace but respect for the rule of law.”

Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake said Nero was afforded the same justice any U.S. citizen would receive and issued a warning to those who would use the officer’s vindication as a cause to stoke unrest beyond peaceful protests.

“We once again ask the citizens to be patient and to allow the entire process to come to a conclusion,” she said. “In the case of any disturbance in the city, we are prepared to respond. We will protect our neighborhoods, our businesses and the people of our city.”

Though some expected protests, it appears that there were no large gatherings as of late Monday evening.

‘It could be a hug’

Nero was charged with second-degree assault for allegedly touching Gray during an arrest that prosecutors said was illegal. He also faced two counts of misconduct, as well as reckless endangerment for not putting a seat belt on Gray when he put the prisoner in a police van.

Gray died from spinal injuries after being shackled without a seat belt in the van.

Williams last week aggressively questioned prosecutors about their assertion that Nero and other officers assaulted Gray by touching him without reasonable suspicion or probable cause.

Prosecutor Janice Bledsoe argued that searching and handcuffing Gray constituted an assault.

“You are saying an arrest without probable cause is a misconduct-in-office charge – is a crime?” the judge asked. “So you say if you arrest someone without probable cause, it’s a crime?”

“Yes,” Bledsoe responded.

Williams at one point said: “If you touch someone, it could be assault, it could be a hug.”

Michael Schatzow, chief deputy state’s attorney, later told the judge that “not every arrest that occurs without probable cause is a crime.” But he added that arrests in which the actions of the officer “are not objectively reasonable” are criminal.

The prosecutor said Nero and his partner turned aroutine stop based on reasonable suspicion of a crime into a full-blown arrest requiring probable cause.

Ultimately, Williams decided that Nero neither arrested nor detained Gray, that Nero had no duty to question the officer who arrested Gray or the officers in the van who should have placed a seat belt on Gray and it wasn’t clear if Nero had received orders or training on securing prisoners in transport vans.

We or he?

In her closing, Bledsoe cited statements in which Nero and his partner both used the word “we” to describe putting Gray on the ground and handcuffing him.

Nero’s partner, Officer Garrett Miller, testified that he detained Gray himself. The state compelled Miller – who’s awaiting trial – to take the stand against Nero with immunity, meaning his testimony cannot be used to incriminate him at his trial.

Bledsoe also told the court that Nero ignored a general order for officers to secure suspects in vans with seat belts.

Defense attorney Marc Zayon said in his closing argument that Nero acted legally and that handcuffing someone who ran from the police was “the right thing to do.”

Zayon said Nero and Miller used the term “we” because they considered themselves a team.

The only time Nero touched Gray was when the suspect asked for his inhaler, Zayon said.

The defense argued there was no proof Nero had read an email about the seat belt order, and that the state had failed to show he had a duty to secure Gray. Zayon said it was the responsibility of the van driver to put a seat belt on the prisoner.

Prosecutors have said that Gray complained of having trouble breathing and asked for medical help as he was driven in the van. When he arrived at a police substation, he was unconscious.

A week later, Gray died at a hospital from his spinal injury.

The case against William Porter, the first officer to go on trial, ended in a mistrial in December after jurors couldn’t agree on a verdict.

Fellow accused officer testifies

What’s next?

Four officers have yet to stand trial – Miller, Lt. Brian Rice, Sgt. Alicia White and Officer Caesar Goodson Jr. The trial for Goodson, the van driver, will start June 6.

Rice’s will start July 5, Miller’s July 27 and White’s on October 13.

Porter will likely face a retrial on June 13.

CNN’s Ray Sanchez, Kristina Sgueglia, Miguel Marquez, Joshua Berlinger and David Williams contributed to this report.