Editor’s Note: Dan Steinbock is the founder of Difference Group and has served as research director at the India, China and America Institute (USA) and visiting fellow at the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China) and the EU Center (Singapore).

Story highlights

Rodrigo Duterte favors greater economic cooperation with China, writes Dan Steinbock

He has been critical of the U.S.-Philippine alliance and leans closer to China, he says

The next likely Philippines President will be more independent in critical economic, political and military decisions - decisions that will also shape Southeast Asia’s future.

Until the 2000s, Manila sought to hedge between U.S. security assurances and China’s economic development. Under outgoing president Benigno Aquino III’s approach, it has allied with the U.S. to balance China – that’s the perception in Beijing, at least.

READ: As Philippines’ likely president, Duterte vows to be ‘dictator’ against evil

Aquino and his foreign minister Albert del Rosario opted for a tougher policy approach toward China and rejected bilateral talks which they saw as futile. The two also pushed the 2014 Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA), which will increase U.S. military presence in the Philippines and has brought the U.S. Navy back to Subic Bay. Concurrently, there have been joint military exercises and increasing cooperation with Vietnam and Japan.

In president-in-waiting Rodrigo Duterte’s era, however, things may shift.

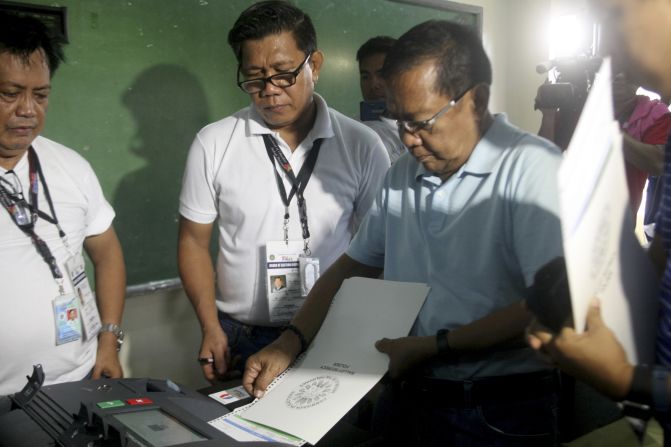

READ: Duterte rival concedes in Philippines presidential election

Philippine voters head to the polls

Balancing or hedging, that’s the question

Duterte is a social-democratic, proud nationalist and foreign policy realist. Unlike Aquino, he would be willing to have bilateral talks with China over the South China Sea. He favors greater economic cooperation with China, has been critical of the U.S.-Philippine alliance and leans closer to China. Despite treaties, he has little confidence Washington would honor its defense obligations.

In Duterte’s view, one-sided cooperation with the U.S. could result in increasing friction, not just with China, but Islamic extremism in the Southern Philippines. Instead, economic cooperation – Chinese capital and infrastructure investment via the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) – could accelerate development in the Philippines.

That’s why Duterte may favor a China policy approach that would be less about balancing and more about hedging.

In this scenario, Manila would seek security benefits from the U.S. defense umbrella and economic returns from trade and investment with China. If successful, it could relieve tensions in the Philippines-U.S.-China triangular relations and, by default, in the South China Sea.

The net effect would be slightly cooler relations with Washington and warmer relations with Beijing – but effective cooperation with each.

Toward a new triangular era

To implement even some of his bold goals, Duterte needs stability at home and in the proximate region. Until recently, the Philippines was a growth pocket amidst the merciless international environment, as exemplified by their fairly strong peso currency.

As advanced economies in the West stagnate and growth slows in emerging Eastern economies, pressures are expected to climb in Manila. This is especially if the U.S. Federal Reserve hikes rates or China’s growth further decelerates. Additionally, if political uncertainty increases after the elections, stability in the Philippines could erode.

In a negative scenario, domestic failures to deliver more inclusive growth could dovetail with a deterioration in U.S.-Philippines relations, or a continued chill in bilateral relations with China, thus raising tensions across the South China Sea.

In contrast, a wary optimist would argue that odds are in favor of positive progress, but only if political destabilization can be avoided at home and trilateral cooperation prevails regionally.