Story highlights

The high court heard oral arguments Wednesday in a challenge to University of Texas admissions standards that take race into consideration

Justices heard the issue three years ago and referred the matter back to a lower court

Supreme Court justices appeared divided Wednesday about the future of a program at the University of Texas that takes race into consideration as one factor of admissions.

The hearing, which was at times tense and went over the originally allotted one hour time frame, revealed some of the same fissures that bothered the justices when the case was heard for the first time in 2012. The three liberal justices on the bench appeared largely supportive of the plan. The conservatives, led with passionate questions from Justices Samuel Alito and Antonin Scalia were at times sharply critical of arguments made by a lawyer for the University.

Justice Anthony Kennedy, who could be a key swing vote in the highly anticipated case, suggested at one point the case should be sent back to a lower court to give the school an opportunity to present more evidence about the plan. Kennedy lamented that even though the court sent the case back to the lower court three years ago it felt like, “we’re just arguing the same case.” Later in the arguments, however, Kennedy seemed to pull back a bit from the idea that a remand might be necessary.

Supporters of affirmative action in higher education are fearful that the court might issue a broad ruling in the case that will curtail a public university’s ability to consider race in order to produce a more diverse student body.

The case comes at a time when students across the country are showing signs of racial unrest. Protests at the University of Missouri broke out earlier this fall over racial concerns that eventually drew the resignation of the school’s chancellor and university system president. At other universities there have been sit-ins and demonstrations.

Read: Supreme Court declines to take up ban on assault weapons

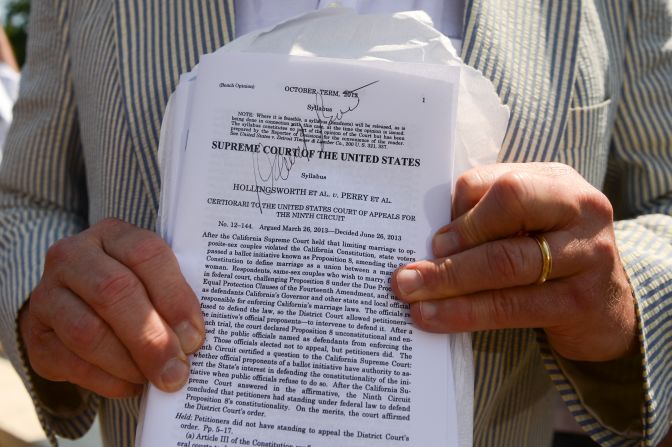

It’s the second time, Abigail Fisher, a white woman from Texas, has come to the court. In 2012, the justices heard arguments and then said nothing for eight months. Ultimately, they issued a narrow opinion sending the case back down to a lower court for another look. The short opinion was indicative that the justices are deeply divided on the issue.

The lower court once again ruled in favor of UT and on Wednesday, eight justices (Justice Elena Kagan recused herself because she dealt with the case in her previous job as solicitor general) sat for another hour-and-a-half of arguments.

Eight states currently have banned the use of race in admissions policy all together, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures: Arizona, California, Florida, Michigan, New Hampshire, Nebraska, Oklahoma and Washington.

Read: Supreme Court takes up ‘one person, one vote’

The Top Ten Percent program

Back in 2008 Fisher was denied admission and sued, claiming discrimination based on race. In Texas, high school seniors who graduate at the top 10% of their class are automatically admitted to the public university of their choice. On top of that program, UT also considers race and other factors for admission.

Since Fisher did not qualify for the program, she applied with other applicants – some of whom were entitled to racial preferences. She was denied admission.

Photos: Supreme Court cases that changed America

Lawyers for Fisher say in court papers that since UT already had a race-neutral plan in place they shouldn’t have layered on another program that takes race into consideration.

Alito pointed to the Top Ten Percent program and suggested that it had been successful in increasing the diversity of the school. He said to Gregory Garre, a lawyer for the university, that he found “troubling” a suggestion “that there is something deficient about the African-American students and the Hispanic students” in the top 10% already. Alito suggested that the school in some way thought the students coming from the Top Ten percent were “not dynamic, They’re not leaders. They’re not change agents.” He added: “I don’t know what the basis for that is.”

Speaking more broadly, Chief Justice John Roberts underlined his concern that the use of race by the school must pass a stringent standard of review from the Court. He told Garre, “We’re talking about giving you the extraordinary power to consider race in making important decisions,” he said.

Roberts noted that court precedent from a 2003 case called Grutter v. Bollinger upheld an affirmative action plan at the University of Michigan law school, but suggested an end date in 25 years.

“Grutter said that we did not expect these sort of problems to be around for 25 years, and that was 12 years ago. Are we going to hit that deadline?” Roberts asked.

Controversial language from Scalia

Justice Antonin Scalia pushed a point that had been made in some friend of the court briefs filed in the case. It concerns a theory called “Mismatch” popularized by authors Stuart Taylor Jr. and Richard Sander that suggests affirmative action programs don’t always benefit minorities.

Although Roberts had mentioned the theory in a different case in 2013, Scalia’s language was blunt.

“There are those who contend that it does not benefit African-Americans to get them into the University of Texas, where they do not do well, as opposed to having them go to a less-advanced school, a slower-track school where they do well,” he said.

“One of the briefs pointed out that most of the black scientists in this country don’t come from schools like the University of Texas,” he said.

Read: Scalia questions place of some black students in elite colleges

The conservatives on the bench were well aware that the case probably comes down to Justice Kennedy. Although early on he suggested the case might need to be sent back down to the lower court, by the end he seemed to move away from that notion.

Garre noted that there had not been a full trial, and Kennedy asked “if you had a remand, you would not have put in much different or much more evidence than we have in the record right now.”

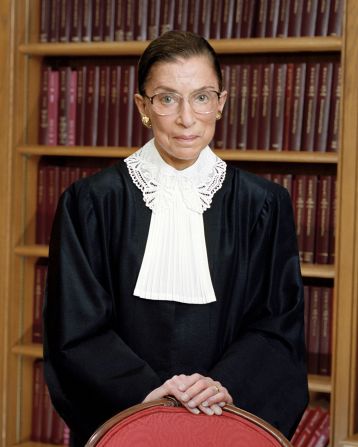

Sotomayor, Ginsberg

The liberal justices indicated they saw no constitutional problems with the plan and were much more receptive to arguments made in favor of the University of Texas.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor spoke up repeatedly. Once she was cut off and she said with irritation, “Let me finish my point.”

She said that even without the Top Ten Percent program, the program put forward by the university complied with court precedent. She said that if a school isn’t allowed to consider race as a part of a holistic review of a student, “then the holistic percentage, whatever it is, is going to be virtually all white.”

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg questioned whether the Top Ten Percent program was race neutral as Fisher’s lawyers contend. She called it “so obviously driven by one thing only, and that thing is race.”

She suggested she thought it wasn’t a good substitute for an admissions program that allows race to be taken into consideration as one factor. “It’s totally dependent upon having racially segregated neighborhoods, racially segregated schools, and it operates as a disincentive for a minority student to step out of that segregated community and attempt to get an integrated education.”

Fisher’s case is being supported by the Project on Fair Representation, a conservative group also behind a case in 2013 that invalidated a key provision of the Voting Rights Act. The group also backed a case heard at the court Tuesday challenging how states draw their legislative lines.

“UT failed to show that its pre-existing race-neutral admissions program could not achieve the desired level of diversity,” her lawyers argued in court papers. “By holding that UT discriminated against Ms. Fisher and reversing the judgment below, the Court will not only vindicate her equal-protection rights, it will remind universities that the use of race in admissions must be a last resort – not the rule.”

Fisher is not asking the court to forbid race-conscious programs all together, but if the court rules in her favor, it could make it so difficult for schools going forward that they may abandon attempts to consider race as one of many factors.

Outside of the court on Wednesday, Sherrilyn Ifill, president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund said, “Conservative activist Ed Blum, who is behind this suit and similar ones, never questions the right of colleges to consider anything other than race – like hobbies, gender, age or hometown.” She added: “To say to a student that everything about you is relevant except for your race, strips away a part of that student’s identity.”

Lawyers for the University say that the Top Ten Percent Program alone isn’t enough because it is based on “just a single criteria” and it excludes consideration of “the broad array of factors that contribute to a genuinely diverse student body.”

They say the current program looks at each applicant as a whole person, “thus offsetting the one-dimensional aspect of the Top Ten Percent Law,” and considers the applicant’s race only as one factor among many to examine the student.

They point out that in the past, attempts to use race-neutral efforts to achieve diversity including scholarships aimed at recruiting qualified students of all races from lower socioeconomic backgrounds have failed. “Nevertheless, UT experienced an immediate, and glaring, decline in enrollment among underrepresented minorities,” the UT lawyers wrote.

According to the University, back in 1998, before it could take race into consideration as a factor for admissions, UT had 199 African American enrollees in a class of 6,744 (3% of the incoming class). By 2008, under the race-conscious policy at issue, that number nearly doubled. For Hispanics, the numbers grew to 20% in 2008.

UT also says there is a major procedural issue that should block the justices from even reaching the merits of the case. They say that because Fisher graduated from LSU in 2008, she lacks the necessary injury – or standing – to bring the case before the justices. Although the issue of standing did not stop the court from hearing and deciding the case before, it was the first question asked by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg during oral arguments three years ago.