Story highlights

John Fetterman is a small-town, hands-on mayor with tattoos

Why is he running for U.S. Senate?

The expansive loft is a former car dealership – everything in Braddock is a former something.

The windows offer a view of Andrew Carnegie’s first steel mill – still in operation. But the town beside mill, Braddock, Pennsylvania, population 2,150, is much smaller than it used to be.

The mayor, John Fetterman, is not small. All 6-foot-8 and 320 pounds of him settles into one of his rustic leather couches for a meeting with three local leaders.

On a day in late October, long before refugees were the hot-button issue of the day, Fetterman and the three guests spend upwards of an hour discussing how to help Syrians seeking refuge in the Pittsburgh community. As they wrap up, talk turns to Fetterman’s then-6-week-old U.S. Senate campaign. One of the guests tells Fetterman it would be easier for him to get things done in Braddock than as a senator in Washington.

“It’s true.”

It’s also true that he’s a long-shot candidate in a crowded field for the Democratic nomination. That hasn’t stopped the media from paying attention to the oversized mayor with the bald head, the goatee and the tattoos, who fits in Braddock but would stick out like a sore thumb in Washington. After following him around in his adopted hometown, it’s a little hard to understand why he would want to.

“That winds my clock”

Fetterman’s Ford F-150 pulls up to the shipping and receiving door behind the Costco in neighboring Homestead. He does this at least four times a week, so when he pushes the call button on a box near the door, an employee opens it and invites him inside. Soon, another employee wheels out a cart with several cases of fresh food and, with Fetterman’s help, begins loading it onto the truck bed.

The food is free – deemed unsellable for one corporate reason or another – but still perfectly safe to eat, and Fetterman knows that because he’ll spend the next few days personally handing it out to his town’s residents. His iPhone will ring, and after a few moments: “That was about a food delivery.”

Minutes later, Fetterman is piling pounds of chicken legs and macaroni and cheese into the arms of a middle-aged woman and her daughter.

“That’s the best part of my job,” he says, driving away. “That winds my clock being able to do that.”

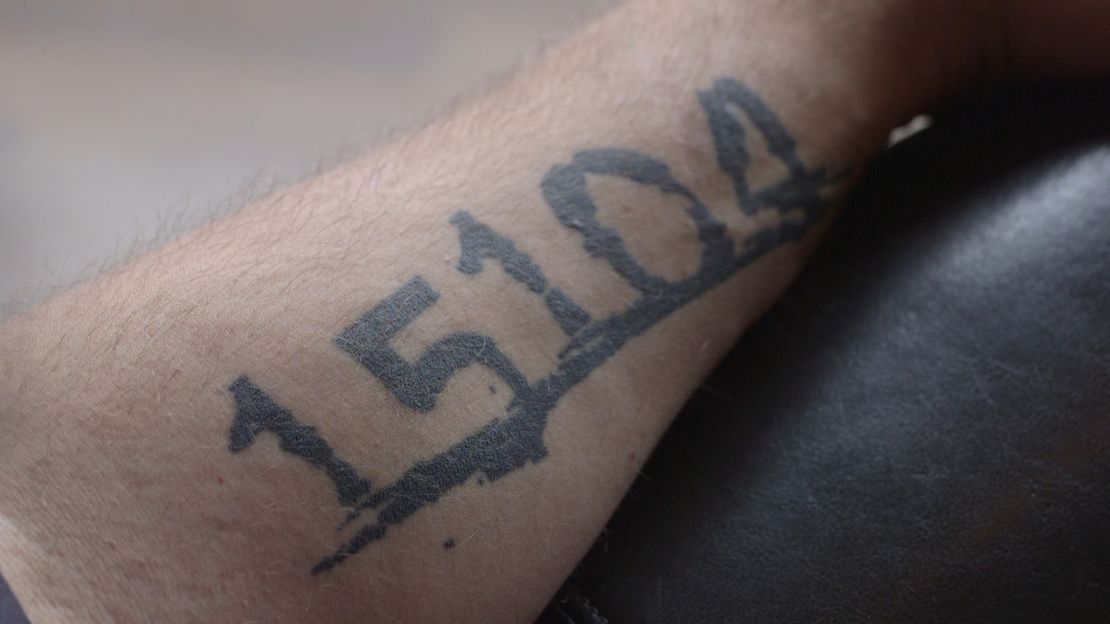

When Fetterman sits to talk with you, he holds his palms upward, and the tattoos running up and down his arms are revealed – if you didn’t notice them earlier. His left arm is emblazoned with 15104 – Braddock’s ZIP code. And on the right, the dates of nine homicides perpetrated in the small borough since Fetterman took office in 2005.

Fetterman doesn’t wear long-sleeve shirts. In fact, it’s hard to find a photo of him wearing anything other than a black, short-sleeve, button-up shirt and cargo shorts.

“I don’t own a suit or a tie and that’s not a statement of rebellion or anything like that,” he says. “It’s out of deference to my community, it’s out of deference to what’s across the street, in terms of the mill.”

“This town was born of sacrifice and it has given so much, and it really almost ran out of stuff to give.”

So Fetterman gives his time and energy to Braddock, about 15 minutes from Pittsburgh, and it’s hard to imagine anyone else physically doing more for the borough than he does.

Driving through the neighborhood where Braddock’s last homicide occurred – a stabbing following a domestic dispute in June – Fetterman spots a man on the side of the road and opens his window.

“You live down on 2nd, right?” he asks. The man’s mother lives on 4th Street.

“Yeah, I left a note there…I can get her gas turned back on.”

Turns out he can do that because of a year-old arrangement with the gas company. People’s Natural Gas gave him a list of the houses in Braddock that had their gas turned off, and he went door-to-door to ask the homeowners about it. There were originally nearly three dozen houses on the list; Fetterman had just brought it down to one.

A storied history

In many ways, Braddock helped build the United States. Edgar Thomson Steel Works opened here in 1872, launching Andrew Carnegie’s network of steel mills and setting Carnegie himself on a path to enormous, unprecedented wealth.

Eighteen years later, the first Carnegie library in the United States opened in Braddock. Nearly 1,700 would follow.

In the 1920s, as the steel industry boomed and the United States built, Braddock’s population swelled to more than 20,000, before precipitously falling decade by decade to 12,000 in 1960.

“When I was growing up here in the ’50s and ‘60s, this whole Braddock Avenue was filled with businesses and theaters and restaurants and you name it,” Braddock resident Pat Morgan says. “You didn’t have to go anywhere else for anything.”

Today, the town has just 2,150 residents, down 90% in the three generations. Ninety percent of the housing and building stock is gone too, Fetterman says.

“If the architecture and the buildings are in place, then things can come back, because you have a place to put them,” he says. “Whereas, here in Braddock, we have to make every building and every space that we save count, because we’ve been missing so much.”

The “Free Store”

The signs of a small revival in blue-collar Braddock are everywhere. A few blocks from the mill, Braddock Farms grows produce (sold at a tiny farmer’s market on Saturday morning). Small signs pepper the telephone poles above parking signs: “NOTICE: Love One Another” or “NOTICE: Turn That Frown Upside Down.”

And then there’s The Free Store.

Welcome to a Bernie Sanders fantasyland. The name kind of says it all: Everything is free. The food, the clothes, the dishes, and the bicycles – all for zero dollars and all without limit. Consisting of two well-adorned shipping containers and a parking lot, the store is the brainchild of none other than Gisele Fetterman, the mayor’s wife, who immigrated to the United States from Brazil and was once undocumented.

One recent Saturday, a self-described Christian minister named James Swift pulled into the lot in a bronze GMC pickup, the truck bed nearly overflowing with boxes. A friend of his was set to tear down a building, so Swift asked to poke around first.

“The more I give, the more God gives to me,” Swift says.

A 15-year-old volunteer named Raemond Prunty backs Fetterman’s truck up to the minister’s so the beds align. Prunty, Swift, and some others transfer the boxes full of brand new, perfectly wearable winter coats, T-shirts and pants from one truck to the other. It won’t be long before the clothes are available, for free, to Braddock residents.

This level of generosity has come to symbolize new hope for a town of such concentrated poverty.

Next to the Free Store, The Brew Gentlemen, a brewery, stands out, designed with a modern, urban flair – very un-Braddock. Inside, Matt Katase and his buddies brew a dozen varieties of beer and operate what Fetterman describes as “the highest-rated brewery in the Pittsburgh area.”

It was born of a school project at Carnegie Mellon University, where Katase studied mathematics. After researching two popular Pittsburgh neighborhoods and hearing some buzz about Braddock, Katase and his business partner gave it a look. The gentlemen brewers, as they were, didn’t just open a business in Braddock – they moved here. They say business has been good, foreshadowing, Fetterman hopes, what Braddock can become.

“There’s just this energy,” Katase says. “We very quickly fell in love.”

A reinvention

Fetterman found his way to Braddock and its energy from a childhood near Reading, Pennsylvania, where he was raised by teenage parents who started out “extremely poor.” His father’s eventual success as a small business owner afforded Fetterman the ability to live comfortably, something he says he took for granted, even though it landed him at Harvard.

He says he “sleepwalked” through much of his young adulthood until the day his best friend was killed in a car accident while on his way to pick Fetterman up.

“You’re 23 years old, and you’re thinking life goes on forever and you don’t have to confront your own mortality and suddenly you can drive to the gym one morning and not even know that you had 15 minutes left to live,” he says.

Fetterman joined Big Brothers and Big Sisters and was moved, he says, by a small boy whose father had just died from AIDS and whose mother would die from AIDS one month later. It was a turning point, Fetterman says, that eventually led him to Braddock.

“I couldn’t process that. I had never witnessed such disparity in person,” he says. “And I became fixated on this concept of, this idea of the random lottery of birth.”

“John Fetterman was born into a household with two parents and plenty of food in the refrigerator and an education and no student debt,” says Fetterman of his own upbringing. “This young boy was born into drug addiction, he was born into poverty, he was born into a world where both his parents, he would have to watch them die under the most horrific of circumstances.”

Fetterman quit his job and moved to Pittsburgh to serve two years in AmeriCorps. He went back to Harvard to get a graduate degree, then moved to Braddock to set up a program helping kids get their GEDs.

His first bid for mayor in 2005 resulted in a tie, so officials reviewed the provisional ballots. Fetterman won by one vote. He won reelection by comfortable margins in 2009 and 2013.

“Some people don’t like him ‘cause he’s not from here, but to be honest with you, he’s done more than any other mayor that we’ve ever had,” says Chris Stambolis, the owner of Stambolis Poultry, which has operated in Braddock continually for the past 63 years. “Take, take, take. They never put back into the town. All the politicians that were here back when Braddock had good times were always taking. They never did anything for the town. So I got to give him a plus on that.”

Senate ambitions

It’s hard even for Fetterman to pin down exactly why he wants to leave Braddock for the gridlock of Washington.

“I want to be able to have an impact on issues that are larger than I’m able to as a mayor of a small town,” he says, listing inequality, gun control, climate change and education as examples. “Policies that helped shape my generation and that would shape the future generations of my children and grandchildren.”

But there are plenty of other Pennsylvania Democrats, well-funded and well-known, who want to tackle similar issues. And it’s a big state. Money to buy TV ads and name recognition could be key in this Senate race.

“We’re going to be outraised, quite frankly,” Fetterman says.

Nathan Gonzales, the editor of the nonpartisan Rothenberg & Gonzales Political Report, says sometimes “the reality of a campaign can be jarring.”

“He has a long way to go before being a contender and even a factor in the race,” Gonzales says. “Until Fetterman can prove that he can raise the money – I just don’t think enough people are going to know who he is, let alone decide whether he should become senator.”

Indeed, he has thus far been vastly outraised by his Democratic primary challengers. Former Rep. Joe Sestak, who lost his 2010 Senate bid to incumbent Sen. Pat Toomey, has over $2 million in the bank. And Katie McGinty, who lost a 2014 gubernatorial bid, has nearly $900,000, according to quarterly filings with the Federal Election Commission.

Fetterman has about $144,000 in campaign donations.

“All I have is this,” Fetterman says of his campaign team and the support he’s received. “All I have is a story.”

“You get to help people.”

Across from the library, fog from a fog machine billows into the Braddock community center. Parents watch their children – some 100 of them – scamper around the annual Halloween Party.

Fetterman waits outside, leaning against his truck, which is blocking traffic from turning up Library Street. He started this Halloween tradition the first year he was mayor, when he lived in the basement of the community center.

“This is Mayor John!” a woman tells her three young grandkids as they approach Fetterman, who’s holding a Costco-sized bag of Halloween candy. The children look all the way up at his hulking figure. “Do you want to be mayor?” he asks one of them.

“I don’t know what that is!”

Fetterman has a simple explanation. “You get to help people.”