Story highlights

CNN's Steven Jiang grew up as a member of the first generation of China's one-child policy

He says he didn't question the strict policy until he began covering an activist opposed to it

China's leaders hope to combat problems of aging society and economic slowdown, he says

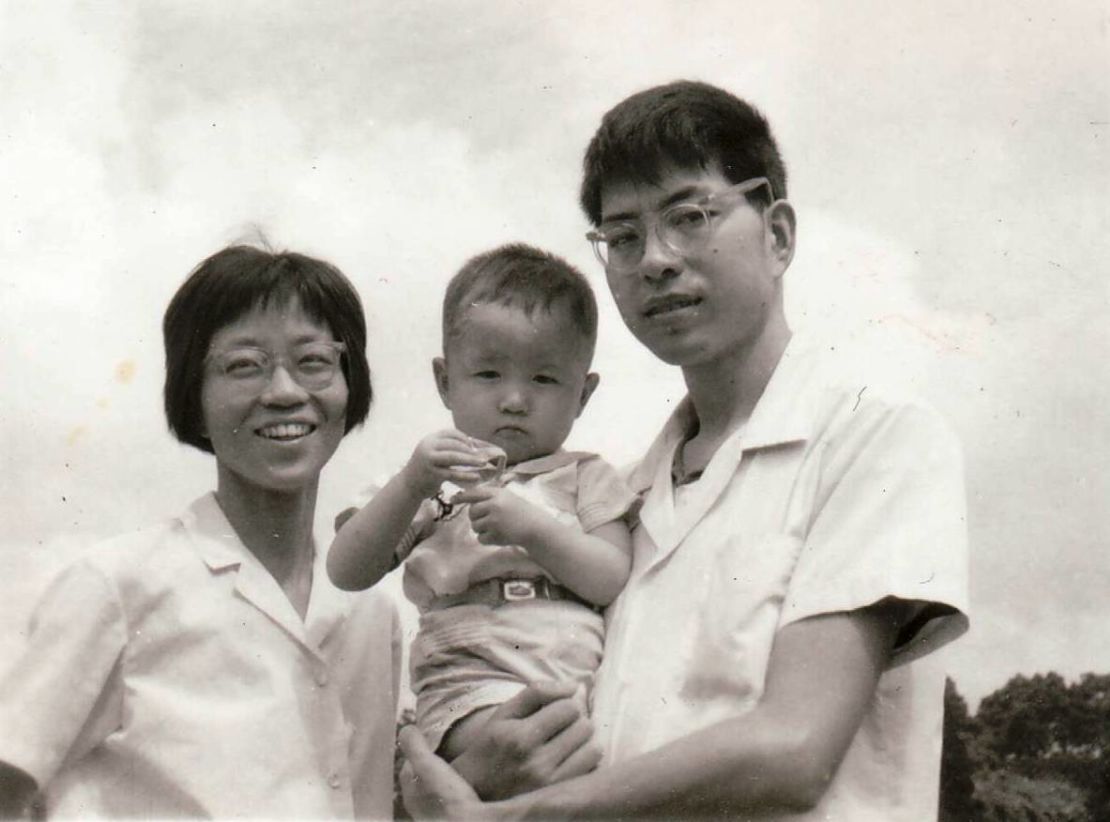

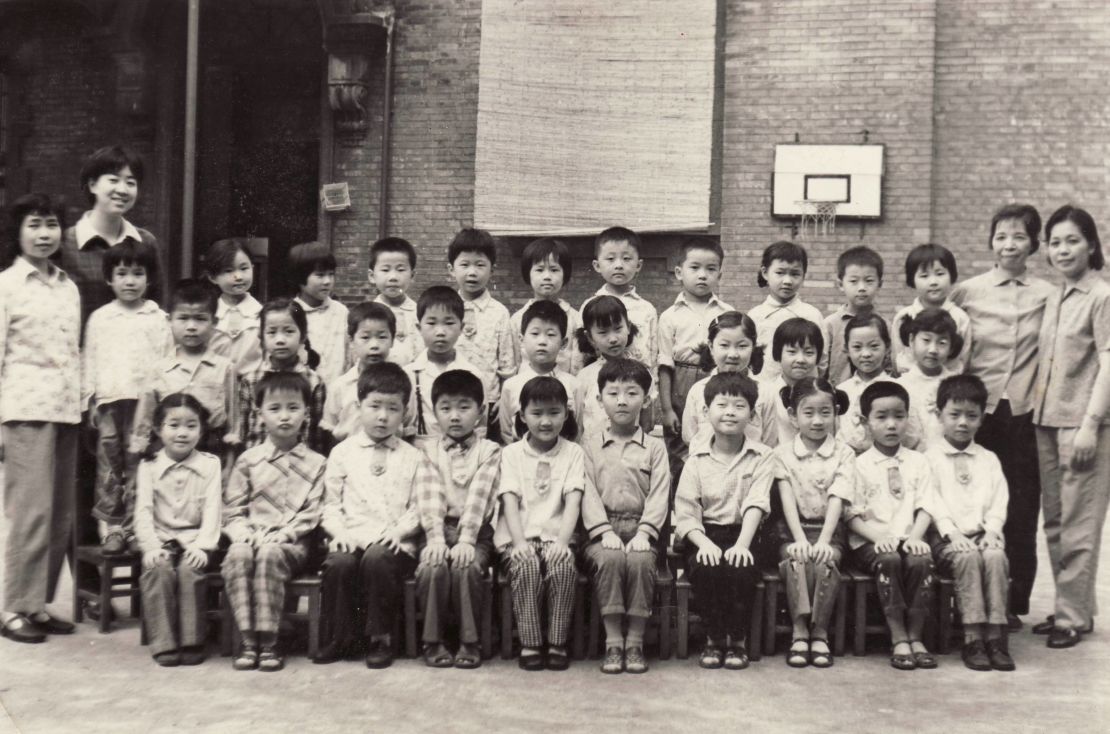

Growing up in Shanghai in the 1980s, I never thought much of the fact that most of my classmates were only children.

Years later I realized that I belonged to the first generation of China’s strict one-child family planning policy, which started in the late 1970s and remained largely intact until the ruling Communist Party decided to scrap it Thursday to allow married couples nationwide to have two children.

READ: China one-child policy to end

My classmates and I all lived close to school – in narrow alleyways lined with three-story houses, each with multiple families packed in. We studied and played together all the time – none experiencing the loneliness that later generations of the single-child policy were said to suffer in high-rise apartments.

It was a simpler time when almost everyone in China – even in its biggest city – was equally poor. Our parents looked way too preoccupied with juggling full-time jobs and full-time parenting to contemplate what life would be like with one more child.

We learned early on in our political education class that “one couple, one child” was a “fundamental national policy.” Most of us bought the party line – not just to pass the required exams – that millions of prevented births helped China develop its economy and improve its people’s living standard.

To many Chinese of my age who grew up in the cities, the one-child policy was just the way it was, and everyone seemed to be fine with it.

It was much later in the United States that I began to stumble upon horror stories blamed on the policy – forced abortions and sterilizations, exorbitant fines slapped on violators and demolition of their homes.

READ: Why the policy update is no silver bullet for economy

After I started covering this issue as a journalist, one person more than anyone helped me put a face on the controversies surrounding the policy.

Chen Guangcheng was a blind human rights activist whose dramatic escape from 18 months of illegal house arrest in the Chinese countryside threw him – and his cause – into an international spotlight.

His supporters maintain his longtime legal advocacy for victims of brutal enforcement of the one-child policy by rural officials had led to his persecution and earlier imprisonment.

As I followed Chen from his village to Beijing and eventually the United States, his stories kept reminding me of the dark side of a policy that the party still credits for the country’s breakneck economic growth in the past three decades.

“One child or two children – the Communist Party has no rights to decide how many children people want to have,” Chen said from Washington, where he now lives, his voice showing no trace of joy about the end of a policy against which he had fought so hard.

“From the central government all the way to the village level, do you know how many family planning officials the system employs?” he asked rhetorically.

“They reap huge economic benefits from the brutal enforcement of this or any policy,” he added. “Too much entrenched interest – that’s why the party won’t scrap the entire family planning system.”

One thing Chen seems to agree with the Communist Party is that China is facing a double whammy of labor shortage and aging society amid an economic slowdown. The activist said he thinks the new policy is “too little, too late,” but the leaders are banking on it to address both of those challenges.

They tested it two years ago by allowing some couples – if at least one of the spouses is a single child – to have two children. By officials’ own admission in state media, however, their target audience – middle-class urbanites – largely failed to respond, citing the high cost of pregnancy and child rearing.

That picture doesn’t seem to have changed much, rendering the immediate impact of the latest policy change minimal.

My cousin Terry, a media executive in his early 30s living in Beijing with his civil servant wife and 6-year-old son, posted a screen grab of my CNN report on WeChat, a popular Chinese social media platform. Above the picture, he wrote: “Bro, even if what you said is true, I can’t afford to have a second one!”

READ: The big winner from China’s two-child policy is …

But the party can’t afford to let China get old before getting rich.

As the curtain falls on the one-child policy in China, I wonder just a little what it would be like to have a sibling.