Story highlights

The Great Clock at London's Houses of Parliament is in urgent need of major repairs

Lawmakers fear Big Ben's famous "bongs" may fall silent if the timepiece is not refurbished

The clock began keeping time in 1859; it has been shut down for repairs several times

The bongs of Big Ben have echoed across London for more than 150 years, thrilling tourists who throng the pavements below, jostling to have their photographs taken alongside the iconic monument.

But the days of setting your watch by the Great Clock could be in jeopardy: the timepiece atop the Houses of Parliament’s Elizabeth Tower is badly in need of repair.

And British lawmakers have warned the clock may stop altogether if it is not refurbished – at a cost of $45 million (£29 million) – in works that would see it shut down for four months.

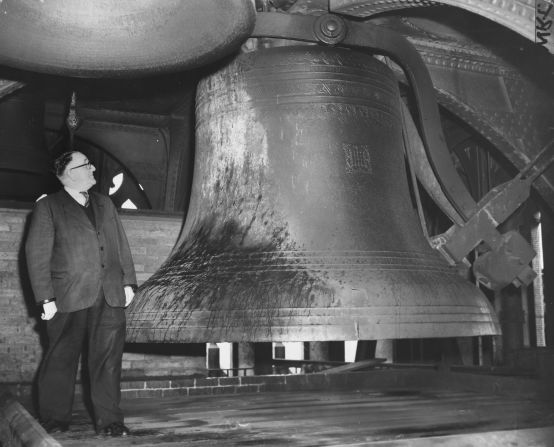

Big Ben is the name of the bell inside the tower (St. Stephen’s Tower, renamed Elizabeth Tower in 2012), and not the building or the clock (simply known as the Great Clock) itself.

According to a parliamentary report seen by both the Mail on Sunday and Sunday Times newspapers: “The clock currently has chronic problems with the bearings behind the hands and the pendulum.

“Either could become acute at any time, causing the clock to stop – or worse.” One source told the Mail on Sunday they believe “or worse” means that the clock’s heavy hands could fall off.

Ringing the changes: Big Ben’s tower renamed

Each of the timepiece’s four 9ft long (2.7 meter) hour hands are made of gunmetal, and weigh in at 660 pounds (300kg) each. The minute hands, made of copper and almost 14ft long (4.2 meter), are lighter, weighing 220lb (100kg) each.

In its plea for emergency funding for the repairs, the report is understood to have claimed the clock is a “symbol of democracy” and warned that a breakdown would cause “international reputational damage.”

Speaking to CNN, a parliamentary spokesman refused to go into detail about the repairs needed – or how much they would cost.

“A feasibility study and survey work has been carried out on the Elizabeth Tower in order to understand in detail the condition of the building fabric, the clock mechanism, and the building services,” he said.

“Committees of both Houses are currently considering the study and will provide advice [on] how best to proceed. No decisions on works, timescales or costs have been agreed.”

The clock first began keeping time in 1859, but Big Ben’s chimes fell silent three months later when the bell cracked; four years later the bell was turned to allow it to ring out once more.