Story highlights

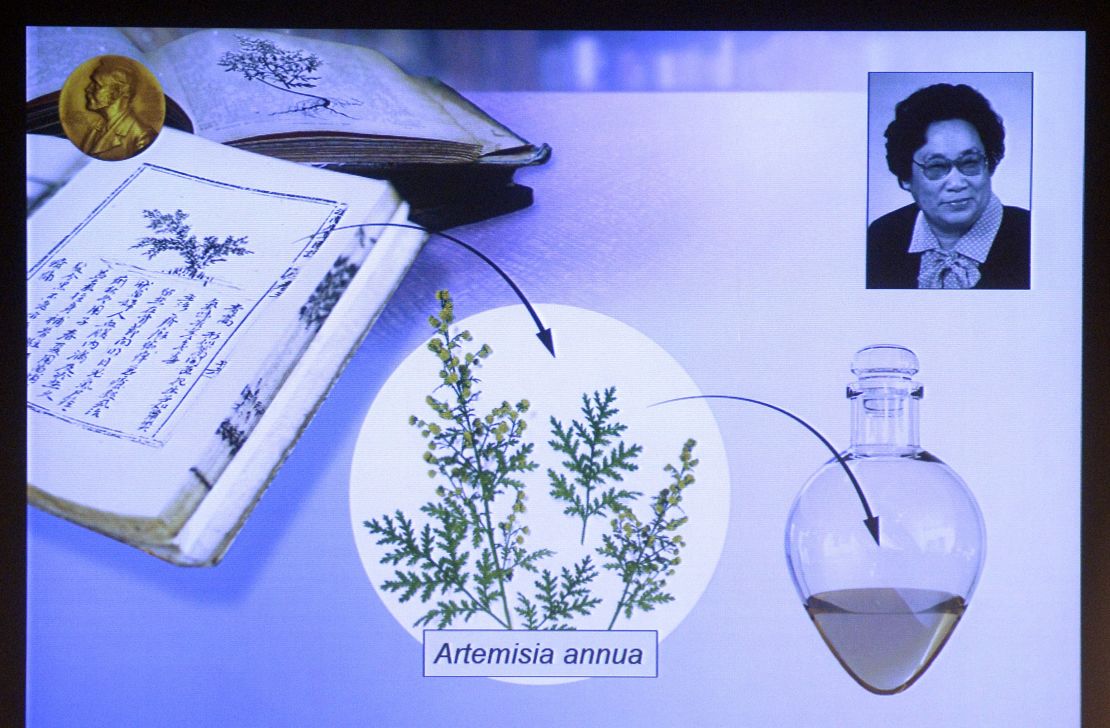

Scientist Tu Youyou combed ancient Chinese texts for a malaria cure

Her research has earned her the highest accolade in medicine -- the Nobel Prize

In the turmoil of China’s Cultural Revolution, scientist Tu Youyou joined a covert mission to find a cure for malaria.

“Project 523,” was set up in 1967 by Chairman Mao Zedong, who wanted to help Communist troops fighting in the mosquito-ridden jungles of Vietnam, where they were losing more soldiers to malaria than bullets.

“We needed a totally new structured antimalarial to deal with the drug resistance. I accepted the task,” Tu recalled in 2011.

She scoured ancient texts and folk manuals and traveled to remote parts of the country for clues, ultimately collecting 2,000 potential remedies. She whittled these down to 380 and tested each one on mice.

One of the compounds tested reduced the number of malaria parasites in the rodents’ blood. Derived from sweet wormwood, its use as a treatment for malaria was first recorded in 1600 years ago in China, when a manual recommended drinking juice extracted from the plant.

Her discovery resulted in the drug artemisinin – humankind’s best defense against the mosquito-borne disease, which kills 450,000 people each year.

On Monday, she was one of a trio of scientists awarded the Nobel Prize for medicine.

READ: 3 scientists share Nobel Prize for work on parasitic diseases

‘Miracle’

Rao Yi, a Chinese neurobiologist, says it’s a miracle the compound was discovered at all, given that most of China’s universities and research institutes were shut down as red guards ran riot across the country during the Cultural Revolution, which began in 1966 and continued for more than a decade

Many scientists, especially those with Western training, were persecuted, he co-wrote in an academic paper published in Science China.

As a result, it wasn’t until 1977 the first academic paper on artemisinin was published. The first English-language research wasn’t published until 1982.

Louis A. Miller, at the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said that many scientists would have given up after early tests showed mixed results. Tu perfected her extraction techniques after realizing that high temperatures were killing the active ingredient.

She also volunteered to be the new compound’s first humantest subject.

“Many people… would have dropped and looked for other things but she pereserved until she had something that worked 100%,” Miller told the Lasker Foundation, which awarded Tu America’s highest medical accolade in 2011 – the Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award.

Since 2000, more than 1 billion artemisinin-based treatment courses have been administered to malaria patients, according to the World Health Organization, contributing to the successful control of Malaria in several endemic countries.

Today, artemisinin compounds form the backbone of malaria treatment and are used in combination therapy to reduce the risk of the development of resistance. Although its success means that there’s a risk of resistance problems resurfacing again.

Controversial figure?

Lu Aiping, dean of Chinese medicine at Hong Kong’s Baptist University, hopes the prize will encourage scientists, both inside and outside China, to explore traditional herbal remedies for new drugs.

Artemisinin is not the only success. Salvianolic acid A, extracted from the root of a danshen plant and ligustrazine, are showing promise as treatments for heart disease. Lu believes there will be many more.

Lu worked with Tu at the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences in Beijing, describing her as “focused” and “concentrated” on her work.

“You definitely couldn’t describe her as easygoing.”

According to the neurobiologist Rao, Tu cuts a controversial figure in China’s scientific community and some feel her recognition has come at the expense other participants in the “523” mission.

“We hope that the Chinese public won’t fall into hero worship, that they should not ignore the efforts of the others,” the paper co-written by Rao said.

Tu made a nod to these sentiments after the award was announced.

“The discovery of artemisinin was an example of successful collective efforts,” she told Xinhua, China’s news official agency. “It’s a gift that traditional Chinese medicine has for the world.”