An ordained reverend raised as a conservative Baptist admits to having a “man crush” on the guy. A rabbi long-steeped in the climate crisis credits him for mobilizing Jews to action. An imam from Syria thanks him for protecting his family and people.

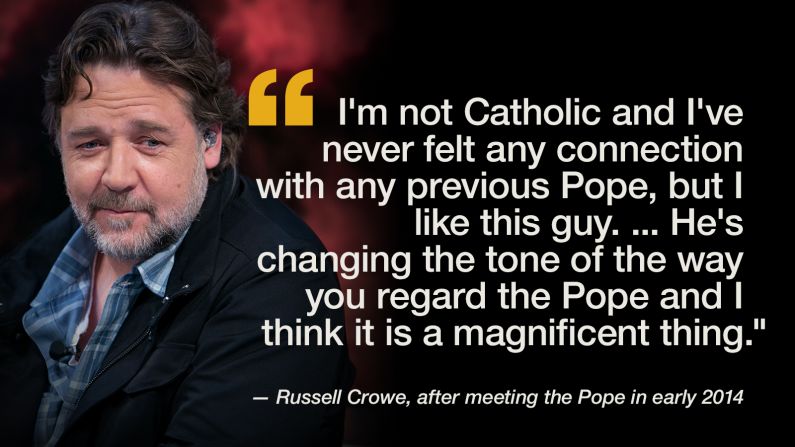

Pope Francis may be the head honcho of the world’s largest Christian church, but since he stepped into the papacy in March 2013, he’s captured hearts across religious – and even nonreligious – lines.

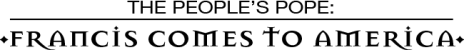

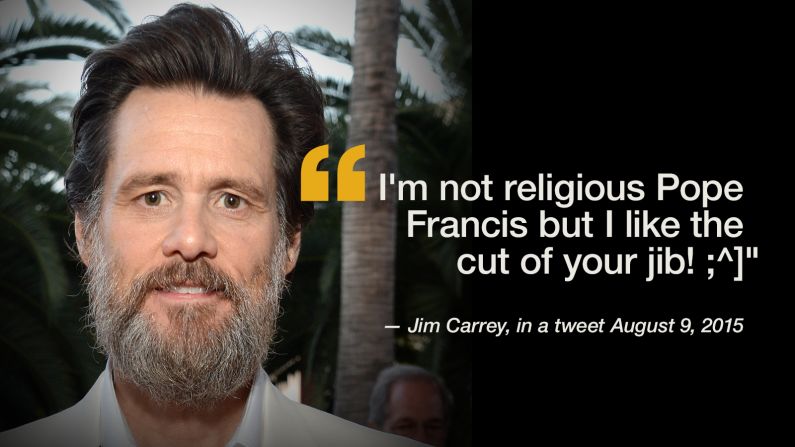

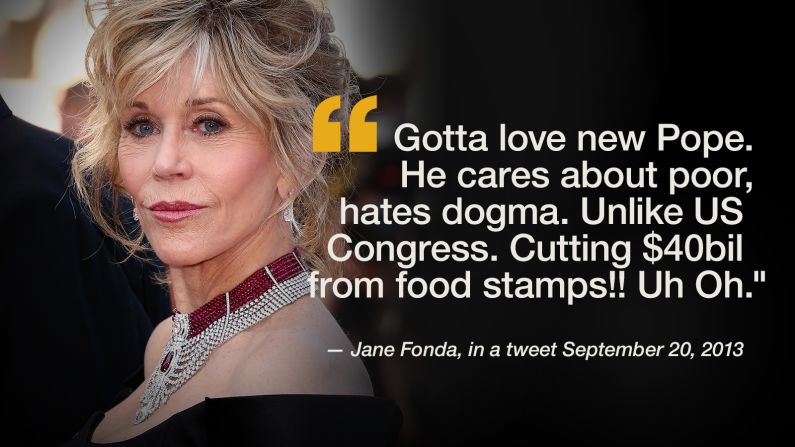

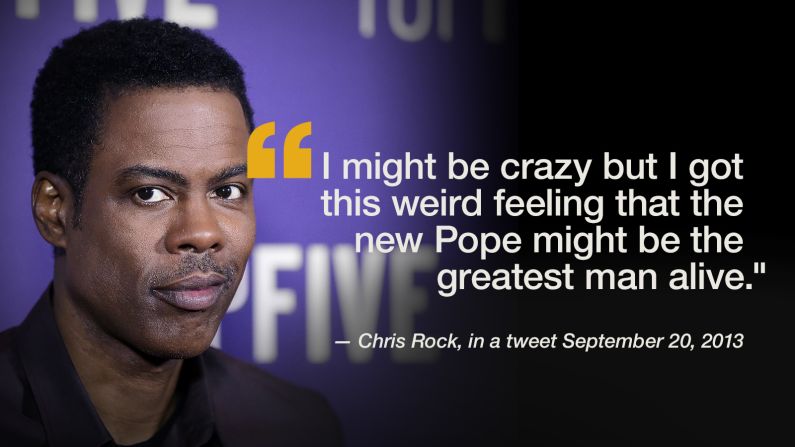

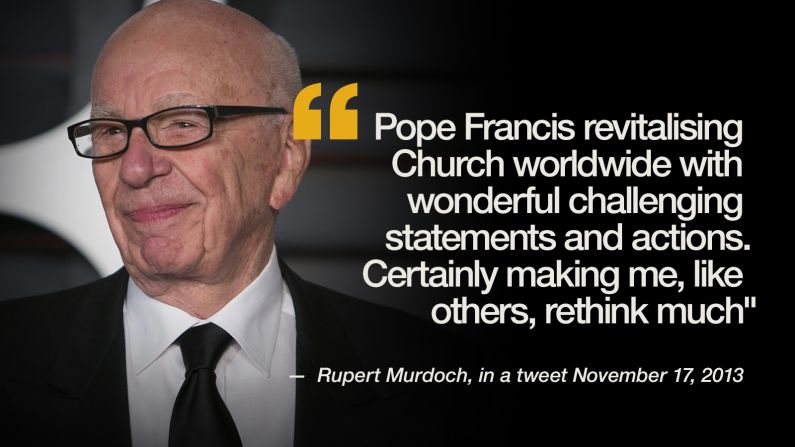

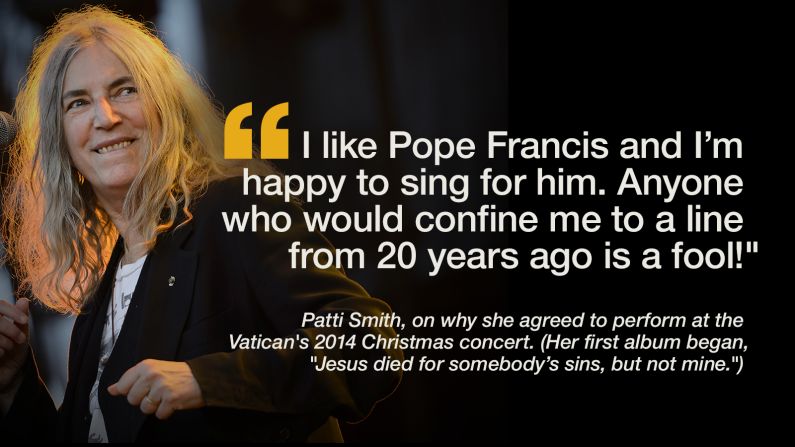

From his acts of compassion, such as his embrace of a severely disfigured man, to his strong statements on the environment and his forgiveness of those who’ve had abortions, this pontiff has sparked a lovefest among non-Catholics. One self-described “staunch atheist” called the Pope a “cool cat” on Twitter. Plenty others also have spread the tweet love.

The much-touted “Francis effect” extends beyond Catholics, that much is clear. But what exactly draws non-Catholics to this pontiff? We reached out to a variety of people across the faith spectrum to find out.

‘Falling in love’

Growing up in a conservative fundamentalist Baptist home and community, Benjamin Corey was taught to be skeptical of Catholics. They were different from him. They worshipped idols, celebrated saints and couldn’t be trusted.

But as he grew, went to seminary and earned several master’s degrees, Corey’s perspective changed. He emerged from his schooling more accepting of others and decidedly on the progressive end of Christianity.

An ordained reverend, he’s taken on pastoral roles in a few churches, most recently as a co-pastor of the Church of All Nations in his hometown of Auburn, Maine, where he served asylum seekers from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

At 39, the full-time writer, speaker and blogger behind Formerly Fundie more than respects Pope Francis.

“I’ve definitely got a man crush on him,” he says with a laugh.

Corey wrote a blog post entitled, “10 Reasons Why I’m Falling in Love With Pope Francis.” In it he gushes about the pontiff’s commitment to social justice, his outreach to the marginalized, his condemnation of “unfettered capitalism,” his modest dress, his lack of judgment of those in the LGBT community – and more.

What he sees is “a Pope who looks a heck of a lot more like Jesus than any predecessor in collective memory,” Corey wrote. “I never imagined that I would find myself connecting with a Pope, and even cheering him on, but this is where I have found myself.”

The Pope has encouraged people of all faiths, and no faith, to find common ground, says Corey. He lives “in an apartment instead of a palace” and has been known to “sneak out for pizza.”

And that time when the Pope washed the feet of juveniles in a detention facility? The image will forever be branded in Corey’s mind.

“The most powerful Christian figure in the world was washing the feet of those who are often the most despised in our culture,” he says. “I just love how he’s just a real person.”

A form of pranam

That moment of washing prisoners’ feet also moved Padma Kuppa, an Indian-born Hindu American living in Troy, Michigan.

In Hinduism, she explains, foot touching is a form of pranam, a respectful greeting reserved for elders and others worthy of deep admiration such as priests, gurus or deities.

“You’re saying, ‘I’m humble before you,’” she says of the gesture. And the Pope’s actions suggested to her that he believes “no individual is less than him.”

Kuppa, a 50-year-old IT project manager, writer and mother of two, is a community and peace activist who celebrates pluralism, focuses on interfaith outreach and serves on the board of the Hindu American Foundation.

In a blog post she wrote for the national advocacy group, she praised the Pope’s inclusion of “don’t proselytize; respect other’s beliefs” in his secrets for happiness. She likened his stance to that of Mahatma Gandhi, who called proselytizing “the cause of much avoidable conflict between classes and unnecessary heart-burning.”

Kuppa speaks of the fourfold pursuits of life in Hinduism. They include artha (prosperity), kama (pleasure) and moksha (liberation). But first and foremost, and most important to her, is dharma.

“It has multiple meanings, but for me it means justice,” she says. She’s drawn to the Pope because of his “dharmic sensibilities” and believes he “embodies that pursuit of dharma.”

She says “equality and dharma go hand-in-hand,” and Pope Francis “lifts up those who don’t have fairness.”

A kindred spirit

For five years, Maggie Leonard, a Presbyterian pastor, has served the underserved. She’s an associate pastor at Mercy Community Church in Atlanta, a nondenominational church with a mostly homeless congregation.

No plates are passed on Sundays for offerings where she is. Since she draws a paltry salary, she babysits on the side to help pay bills.

Leonard, 32, sees in Pope Francis a kindred spirit.

Beyond the simplicity with which he lives and in how he dresses, she points to his pastoral care and his commitment to giving people dignity.

She rattles off developments around Vatican City under this pontiff that make him worthy of extra praise: The newly installed showers, so the homeless who flock to the area have a place to wash. The volunteer barbers who show up each Monday to give free haircuts. The Vatican-issued sleeping bags given out to the homeless who increasingly camp out near St. Peter’s Square. The enlistment of the homeless to help pass out prayer books when the Pope gives his weekly address.

At her church, most of the volunteers live on the streets. Members are offered meals, prayer and classes – including art, yoga and writing. The congregation rents space from another church and isn’t able to build showers – but it welcomes people to take birdbaths in its sinks. Volunteers from other local churches pick up and do laundry for the homeless, allowing the church to fill its clothing closet with clean options so no one need leave feeling ashamed.

Like others, Leonard points to the time in 2013 when Pope Francis washed the feet of juveniles in a detention facility. It was Holy Thursday, a day when she says popes traditionally wash the feet of bishops and priests.

A girl asked Francis why he was doing this, Leonard says, and he answered, “Things from the heart don’t have an explanation.”

“He doesn’t have to rationalize it,” she says, “because he knows where he’s being led.”

Bridges of understanding

From the get-go, the Pope’s name choice carried special meaning for Imam Mohamad Bashar Arafat.

The pontiff’s namesake crossed enemy lines to meet with the sultan of Egypt during the Crusades in the 13th century. While St. Francis of Assisi’s intention may have been to convert the sultan, he instead walked away calling for peace between Muslims and Christians.

“He was impressed by the level of spirituality within the Muslim community and saw something he’d never seen before,” says Arafat, the president of the Baltimore-based Civilizations Exchange and Cooperation Foundation, which works to bring people together in peace. “It was a transformative experience, and he came back completely against the Crusades.”

This respect for others is manifested in Pope Francis, Arafat says, and for that this imam could not be more grateful.

Arafat came to the United States from Syria 26 years ago but has family still in Damascus. So even as he serves as the president of Maryland’s Islamic Affairs Council, lectures at universities, leads programs through the U.S. State Department and with U.S. embassies, his mind and heart often turn to his concerns for those struggling abroad.

Pope Francis, early on in his papacy, spoke out against military strikes in Syria – emerging as a pro-peace voice at a time when Arafat felt it was needed most.

As a guest of the U.S Embassy to the Holy See in October 2013, the imam was able to visit the Vatican, address various groups in Rome and share his appreciation – not just for Pope Francis’ opposition to military strikes in Syria but also for visiting the Italian island of Lampedusa. There the Pope prayed for migrants who’d been lost at sea. Among the dead are thousands who’ve fled violence and despair in Syria. Earlier this month, the Pope called on Europe’s Catholic parishes to take in refugee families.

The Pope has stood for those who are hopeless. He’s built bridges of understanding. And he’s a model of what is needed, Arafat says. Theological differences should be set aside in the pursuit of a better world for all.

“I see him trying to emulate St. Francis in outreach,” the imam says. “It is our responsibility as a Muslim community to raise our voices and say thank you.”

Space for others

The pope’s first full day in the United States will be spent in Washington meeting with President Barack Obama, praying with U.S. bishops and canonizing a Spanish-born Franciscan friar.

Meantime, at the Lincoln Memorial, Rabbi Arthur Waskow will help lead a special Yom Kippur service open to all faiths on the Jewish Day of Atonement.

Collectively, Waskow says, the group will atone for the “misdeeds of all cultures in dealing with the world” and, using a play on words, “reaffirm at-one-ment with the Earth and with God.”

After this service, Waskow and others plan to attend a Franciscan led multireligious celebration in honor of the Pope.

What drives this 81-year-old rabbi, a longtime political activist and founder of Philadelphia’s Shalom Center, is his concern about the climate. It’s been the focal point of his work for a decade and has spawned events like a pre-Passover service to challenge the “Carbon Pharaohs” and the Koch brothers.

Inroads have been made in stirring up interest in the Jewish community, he says, but advance word that the Pope was drafting an encyclical on the environment galvanized efforts.

“We knew the Pope was going to mobilize the kind of energy that very few religious leaders can do in the world,” Waskow says. “There had to be a Jewish statement. … We felt a coming together in all of this, a response to the crisis and a response to the presence of God in the world.”

Thus was born “A Rabbinic Letter on the Climate Crisis,” originally drafted by Waskow and honed through a collaboration with others. It has been signed by more than 400 rabbis from across various Jewish denominations. It references Torah text, extends respect to scientists and outlines concerns and suggestions for action. It is a “call for a new sense of eco-social justice – a tikkun olam [healing of the world] that includes tikkun tevel, the healing of our planet.”

Already it has paid dividends, prompting at least one citywide Jewish action conference planned for later this year in Philadelphia. A smaller conference in northwest Philly, which will include synagogues and churches, will be held on October 4. That day is significant in that it falls on the Feast of St. Francis of Assisi, the Pope’s namesake, and during Sukkot, a Jewish harvest festival that also marks the 40 years that Israelites wandered in the desert.

The last time Waskow remembers being this excited about a pontiff was more than half a century ago. That was when Pope John XXIII, whom Pope Francis canonized, intervened during the Cuban Missile Crisis, releasing a papal statement calling on world leaders to avoid disaster and issuing a 1963 encyclical on peace and nuclear disarmament.

Just as that encyclical inspired Waskow’s earlier focus on combatting the nuclear arms race from a Jewish perspective, so too has Pope Francis’ encyclical bolstered The Shalom Center’s top cause today.

“The fact that he was moving on this,” the rabbi said, “opened up a lot of space for others.”

Standing firm

While many non-Catholic fans are drawn to the Pope because of his progressive ideals and openness to others, that’s not true for everyone.

The Rev. Bill Owens Sr. is president and founder of the Coalition of African American Pastors, which works to promote traditional family values.

“When it comes to homosexuals, we don’t condemn them. We don’t put them out. We should be open to fellowship. But when it comes down to marriage, that’s where I draw the line,” says Owens, who splits his time between Memphis, Tennessee, and Henderson, Nevada.

Owens, who’s had ties to the National Organization for Marriage and was a featured speaker at this year’s March for Marriage, has been outspoken in his criticism of President Obama for endorsing same-sex marriage. In an address to the National Press Club in 2012, Owens compared the president to Judas for betraying black voters, saying he’s “a disgrace and we are ashamed.”

“The President is in the White House because of the civil rights movement, and I was a leader in that movement,” Owens said. “I didn’t march one inch, one foot, one yard for a man to marry a man and a woman to marry a woman.”

Owens, 76, sees in the pontiff an ally he doesn’t have in Obama. He applauds Pope Francis because he has “stood firm on the fact that marriage is between a man and a woman” – even though the pontiff has famously said of gays, “Who am I to judge?”

“We may not agree with all of [the Pope’s] decisions,” says Owens. “But I wish more of our leaders would follow his lead in being vocal despite all the criticisms they may get.”

A friend and fellow lobbyist

Anthony Manousos of Pasadena, California, calls himself a “convinced Quaker.” Now 66, he became convinced in his 30s.

What faith was he before?

“The better question is: Was there a faith I wasn’t part of?” he says with a laugh, before rattling off his spiritual road map. Among the stops he made along the way: He was baptized Greek Orthodox, raised Episcopalian and became agnostic as a teen. He followed Timothy Leary and found Christ after college before becoming a Quaker. Since then, he’s spent months in a Zen Buddhist center, enjoyed a 20-year-marriage to a Methodist pastor until she passed away, and is now married to an Evangelical Christian. Ever since 9/11, he’s fasted during Ramadan and has also fasted on Yom Kippur.

“Though I’m a Christian Quaker,” he says, “I see the light in every religion.”

He’s never been a Catholic, but the former college English professor and Quaker magazine editor has watched the pontiffs and has opinions.

“I think [Pope Benedict] meant well, but he seemed to be more interested in shoring up the church than in issues of social justice,” says Manousos. “This Pope seems to be putting the concerns of the poor, social justice and the environment ahead of everything else.”

He points to the Pope’s encyclical and calls it a “game changer.” Yes, it is a strong statement on the global climate crisis, but it also includes talk about “toxicity of war.” And that is significant to Quakers, who see the world through an anti-war lens.

“Pope Francis calls on all people to care for God’s creation and recognizes that one of the greatest threats to the environment, and to human betterment, is war,” Manousos wrote in a blog post.

“The Pope is clearly aware that conflicts over resources, caused by climate change and political systems dependent on war, will escalate unless steps are taken to live sustainably,” he wrote. “I would argue that we cannot solve our ecological crisis if we don’t dismantle the war system that pollutes and dominates the world.”

The fact that the Pope chose his name from a saint who shunned the Crusades only adds to his appeal. In Francis, this Quaker sees “a lobbyist par excellence” and a friend.

Watching with fascination

Around the same time Sherilyn Connelly came out as an atheist, she also came out as transgender.

This double whammy in her 20s is what inspired her contribution, “The Permanent Prodigal Daughter,” to a book entitled “Atheists in America.”

Connelly, 42, a writer, film critic and librarian based in San Francisco, refers to herself as a “lapsed Catholic.” And it’s from this position, as an outsider looking in, that she follows Pope Francis with deep curiosity.

“I really appreciate and find it fun to watch how he’s completely rattling the mainstream Christian firmament,” she says. “Just look at the s**tstorm that erupted when he washed the feet of the Muslim prisoners. … It’s fascinating.”

Growing up, Connelly says, Catholicism felt like an intrusion in her life. She hated being dragged out of bed on Sunday mornings and forced into nice clothes – and not just because they were boys’ clothes. She doesn’t disparage the actual church and has fond memories of plenty of the people she knew then, “but the whole God thing never made any sense to me at all.”

At a certain point it dawned on her that it was just by chance that she was born into a Catholic family. Had she been born in India, she suspects she would have been Hindu or Muslim. And that realization “blew the logic of the whole thing,” she says, leading her to realize no one belief system could claim to be the right one.

That said, she sees in the current pontiff a refreshing commitment to being nice and merciful to others. But like the 89% of ex-Catholics who, even with their appreciation for the Pope, told a Pew survey they can’t imagine returning to the Catholic fold, neither can she. Not least of all because she still doesn’t believe in God. Pope Francis, though, has given her “a degree of faith … that compassion is returning to religious thought.”

And for that, Connelly says amen.