Editor’s Note: Laura Coates is a former Assistant United States Attorney for the District of Columbia and trial attorney in the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice. She is a legal commentator and Lecturer of Law at the George Washington University School of Law. Follow her on Twitter: @thelauracoates The opinions expressed in this commentary are hers.

Story highlights

Laura Coates says the law requires Davis to certify valid marriages despite her personal objections

Public officials have duties they must carry out according to the law, Coates says

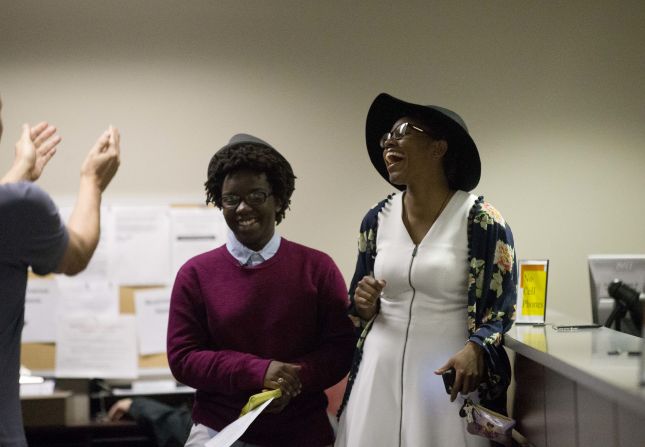

A federal judge was right to hold in contempt and jail Kim Davis, the Rowan County, Kentucky, clerk who refused to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples.

Davis has no legal justification to break the law. She is not exercising civil disobedience. She is practicing official misconduct.

Although her religious convictions appear steadfast, her actions are completely unlawful. Her argument is based on the erroneous and naïve premise that the judiciary is powerless when its orders conflict with your personal conscience.

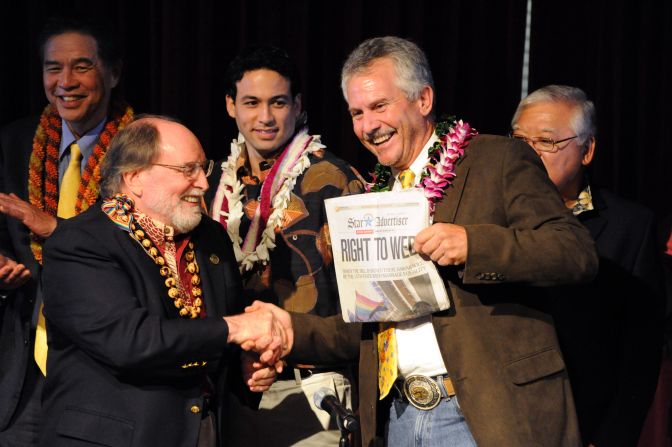

Indeed, nothing can be further from the truth. The history of civil rights and liberties in this country demonstrates that the Supreme Court often acts to force the hand of individuals to promote the greater social good.

As a prosecutor, I couldn’t selectively prosecute individuals based on the laws with which I personally agreed. I was sworn to honor and enforce the laws as they were written. As an elected official, Davis can disagree with the laws, but she can’t simply choose to disobey them.

She is not a private baker refusing to make wedding cakes for same-sex couples. She is an elected official with limited autonomy, who is required to perform her official duties, not the least of which includes certifying that a couple meets the legal requirements for marriage.

By refusing to issue marriage licenses, Davis is attempting to hold marriage equality hostage. And although she has claimed to be denying licenses “under God’s authority,” the only duty she is being asked to perform has nothing to do with religion.

She is not being asked to personally condone or philosophically accept homosexuality. She is being asked to confirm whether the applicants meet the statutory criteria for marriage. And, under state law, and the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges in June, the applicants do in fact meet that criteria.

Contrary to her attorney’s belief, the Kentucky Religious Freedom Act doesn’t salvage her case. It’s true that the state cannot unduly burden her religious beliefs on a whim. But it is also true that the state can subordinate your personal beliefs if there is a compelling state interest and the state is using the least restrictive means to carry out its objective. The state simply requires her signature on a form, not a profession of personal acceptance. It doesn’t get any less restrictive than that.

Davis demanded even more – not only should she be allowed to not issue licenses, no one in her office should be allowed to, either, because her name may still be on the document. It’s the equivalent of the sophomoric idea:”If I can’t do it, nobody can.”

There is absolutely no requirement whatsoever that the state must revamp its licensing system to accommodate her personal beliefs. To do so could lead to the inefficient domino effect, with every person passing the hot potato while trampling on applicants’ civil rights.

In an amicus brief, Kentucky Senate President Robert Stivers had the audacity to ask the District Court to “temper its response” to Davis and not judge her too harshly until the state laws and mindset had a chance to catch up to the Supreme Court’s mandate. This request would be laughable if it weren’t so reminiscent of the southern states’ arguments in Brown v. Board of Education that led to a mandate of school desegregation with “all deliberate speed.”

Time revealed that the vague mandate enabled states to take their sweet time enforcing the laws. In fact de facto segregation in our nation’s schools persists to this day because the court allowed states to legally lollygag. This case is no different.

We maybe one nation under God, but we are a democracy under the Constitution, as interpreted by the Supreme Court.

Alas, despite her contempt of the law, Davis can’t simply be fired. Because she is an elected official, she has to be impeached by the state legislature and tried by the state senate, in what is often a protracted and lengthy process. Fining her, while expected and indeed advocated by her opponents, may ultimately have come at the taxpayers’ expense. Score one for Davis. But, as we saw today, Davis can be jailed, like any other criminal who breaks the law.

Score one for justice.

Join us on Facebook.com/CNNOpinion.

Read CNNOpinion’s Flipboard magazine.