Story highlights

NEW: Amid chants and cheers, the Confederate flag is taken down from the South Carolina Capitol grounds

Born in 1861, the Confederate battle flag basically disappeared after the Civil War

It re-emerged during the civil rights movement; South Carolina raised it over the State House in 1961

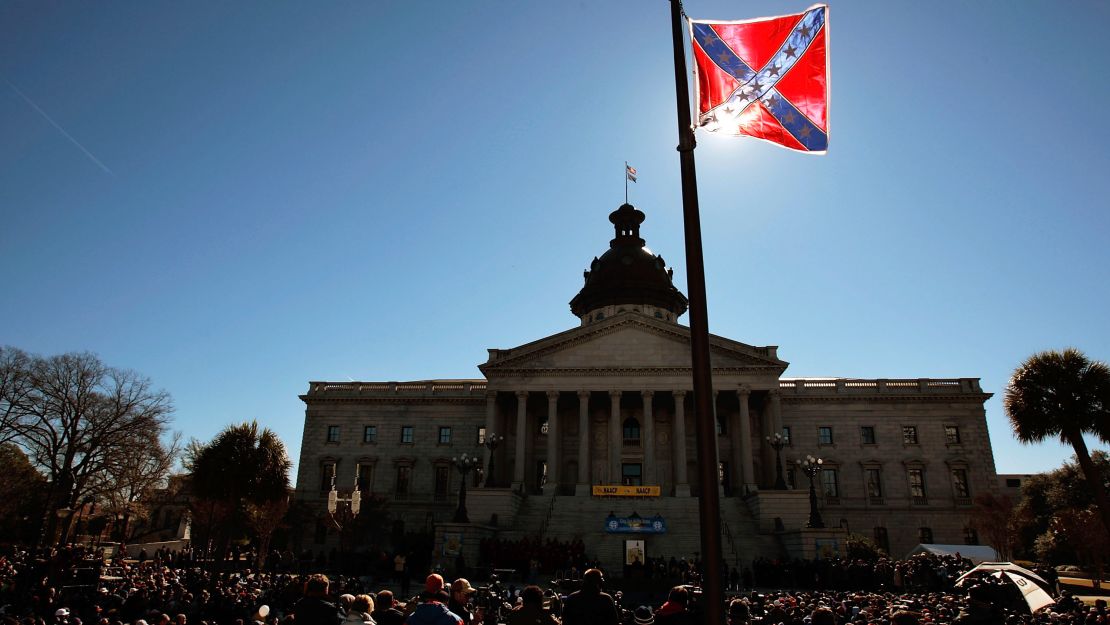

For 54 years the Confederate battle flag fluttered in the breeze on South Carolina’s Capitol grounds – proudly, defiantly. Through passionate pleadings and stormy condemnations to lower it, to hide it from plain sight.

On Friday morning, it came down.

It was lowered for the last time, furled and sent to the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room & Military Museum, where it will be housed.

The political winds changed quickly for the flag after a racist massacre at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston in June.

The steadfast support for the flag as an affirmation of Southern heritage waned against the overwhelming awareness of the battle flag’s deeply painful meaning: a banner of racial subjugation for many.

It was time to go.

The ceremony was brief. There were no remarks. But that didn’t mean it wasn’t full of emotion, including loud cheers and even chants of “U.S.A.” and “Nah, nah, nah, hey, hey goodbye.”

Like the flag’s presence itself, the cheering was loud.

From its origin in the battlefields of the Civil War to its place in a museum, here’s a time line of the rebel flag that flew over the South Carolina State House:

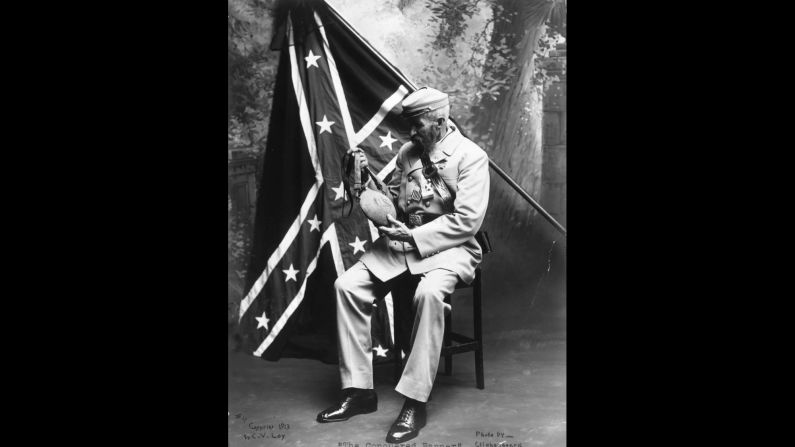

1861: Born of battle

Evolution of the Confederate flag

The Confederate battle flag was designed to stick out, to be recognizably different. It was never the political flag of the Confederate states, although it was integrated into it over the course of the Civil War war into its canton – its upper left field.

The original Confederate flag looked much like the Union flag at the time. So much so, that soldiers on the battle field had a hard time telling the two – and their respective armies – apart, when gun smoke clouded the theater. Confederate Gen. Pierre G.T. Beauregard wanted something vividly dissimilar. Politician William Porcher Miles came up with the design we know today – the battle flag: a blue St. Andrew’s Cross with white stars on a red field.

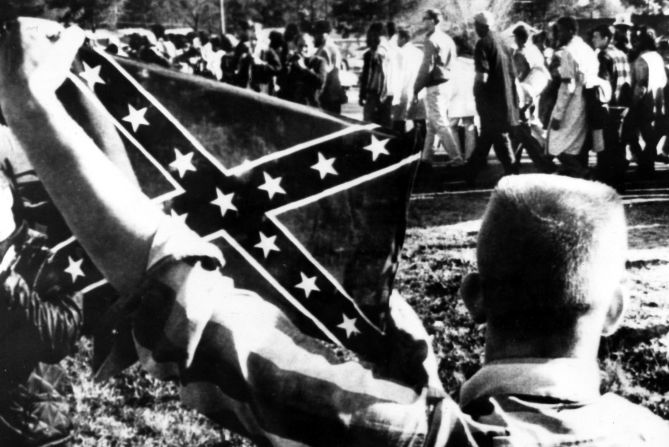

1961: Resurrected over the Capitol dome

After the Civil War, the battle flag mostly faded from sight. But little less than a century later, after World War II, the civil rights movement began to simmer, and the flag slowly reappeared. South Carolina politician Strom Thurmond ran for president as the face of the newly founded racial segregationist party, the Dixiecrats. He was often greeted at rallies with Confederate battle flags.

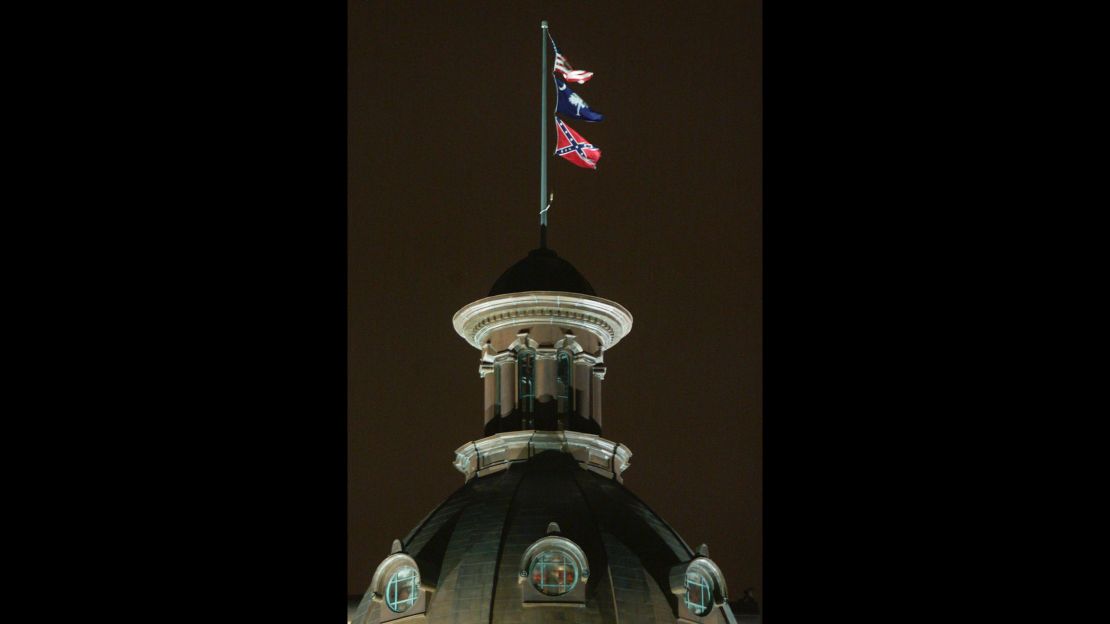

By the 1960s the civil rights movement was bursting forth. In January 1961 John F. Kennedy was sworn in as President, promising equal rights to African-Americans, and desegregation progressed. Three months later, on April 11, 1961, South Carolina hoisted the battle flag over the Capitol dome in Columbia to honor the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the Civil War. And kept it there.

2000: Moved to a lower spot

Political uproar over the flag over the dome grew. And in 2000, civil rights activists succeeded in lobbying to have the large Confederate flag removed from that prominent position. As a compromise, the legislature passed the 2000 Heritage Act, which had the flag raised next to a soldiers’ monument and protect its position there. It required a two-thirds majority vote by the legislature to overturn it.

New Orleans grapples with its Confederate past

June 17, 2015: Stained by a massacre

On June 17, Dylann Roof sat down for Bible class in a historic African-American church in Charleston. For an hour, he listened to the lesson given by Rev. Clementa Pinckney, who was also a state senator. Then, he drew a semi-automatic pistol and told the class that he had come to kill black people. He shot dead nine, including Pinckney, and fled. Soon after his arrest, photos surfaced of Roof holding a pistol and the Confederate battle flag, which he revered as a symbol of white supremacy.

June 18, 2015: Marked for removal

The next day, Gov. Nikki Haley had the American and the South Carolina state flags flying over the Capitol dome lowered to half-staff. But the Confederate flag on the state Capitol grounds continued to fly, defiantly, at the top of its mast. Social media erupted with outrage.

A day later, Roof faced loved ones of his victims via video link. They showered him with forgiveness and grief and prayed for his soul. And public sympathies for their pain deepened. It triggered a chain reaction. Conservative politicians, who in the past defended the flag, called for its removal. And businesses such as Walmart and Amazon struck the flag from their stock.

June 27, 2015: Brought down by an activist

President Obama gave a rousing eulogy at Pinckney’s funeral that turned into an oratory calling for national unity on race. At the end he broke into a rendition of “Amazing Grace.” A bipartisan group of mourners flew in from Washington, giving the memorial the character of a state funeral.

The next day, on June 27, activist Bree Newsome shimmied up the flagpole and took it down but was arrested, and the flag was re-raised.

July 8, 2015: Voted out by numbers

The state Senate swiftly passed a bill to remove the flag permanently from its pole. But when it hit the House floor, roadblocks went up. A handful of Confederate flag supporters introduced 68 nit-picking amendments – effectively holding up a vote on the Senate bill. Republican Rep. Jenny Horne, could take it no longer. She took to the podium to address the chamber, looked over to her black legislative colleagues, then blew up in tears in a fiery speech.

“I cannot believe that we do not have the heart in this body,” she said, pausing to swallow her sobs, then raising her voice to shout, “to do something meaningful, such as take a symbol of hate off these grounds on Friday.” She thrust her finger at the floor with every word of her demand. After half a day of legislative battle, the House overwhelmingly passed the bill.

Pentagon: Confederate base names won’t be changed

July 10, 2015: Sent to its resting place

On July 9, Haley signed the bill into law with nine pens, one for each of the victims killed at Emanuel AME Church. The pens were made gifts to their loved ones.

On July 10, around 10 a.m., two members of the South Carolina state highway patrol, took down the flag the Confederate flag and then handed it to Leroy Smith, director of South Carolina’s Department of Public Safety. Smith is African-American.

Now it takes on a new life – this time as a museum piece.