Story highlights

Hospice is available across the U.S. for patients with a terminal illness, usually with no out-of-pocket costs

Many patients do not start getting hospice services until their last days of life, missing out on potentially months of support

Most of us would prefer to put the thought of hospice and end-of-life care as far out of our minds as possible.

True, the health problems that make a person need hospice care – terminal illness — are never reason to celebrate. “[But] hospice is not about giving up. It’s about living as fully as possible with your condition,” said Jon Radulovic, a spokesperson for the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, a nonprofit membership organization made up of hospices and hospice providers.

The best time to think about hospice care is after you or a loved one receives a serious medical diagnosis, Radulovic said, thinking of “what priorities are important and what options might be available.”

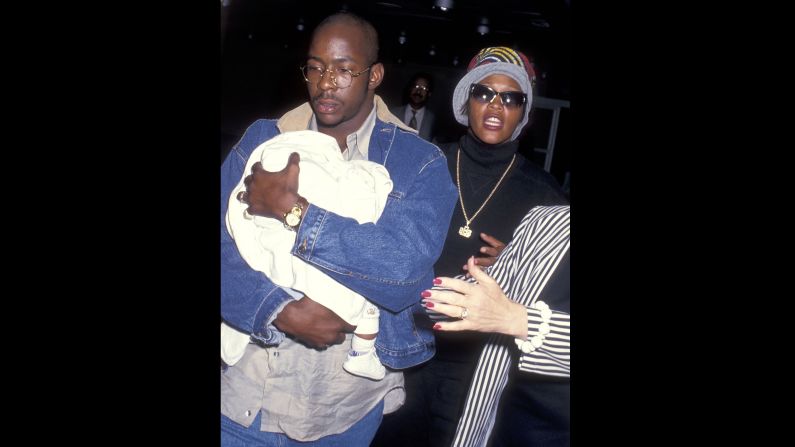

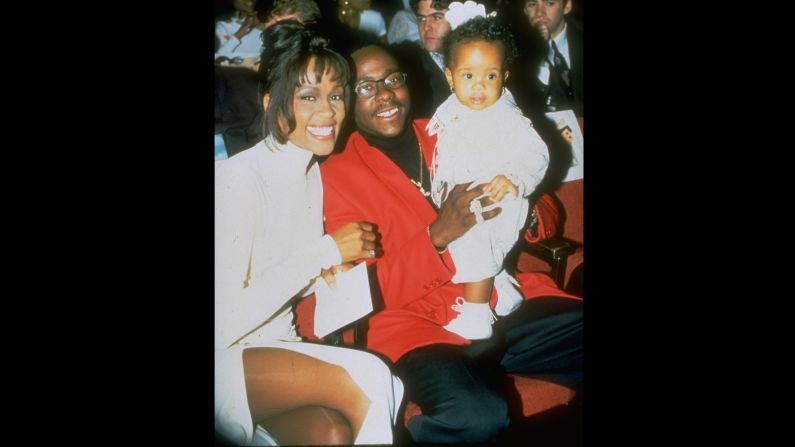

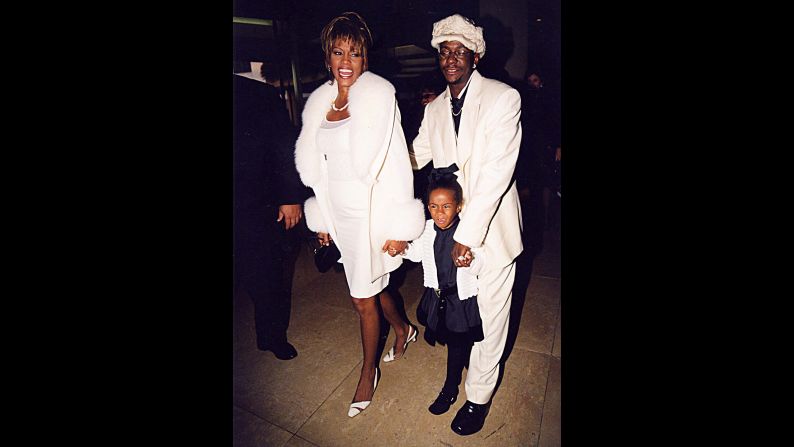

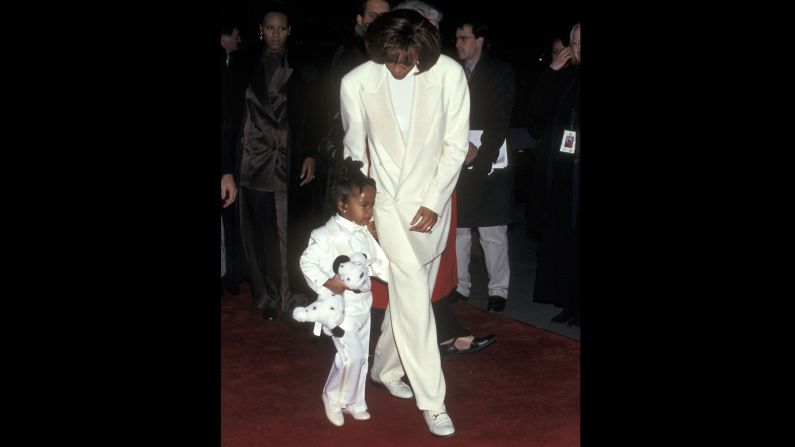

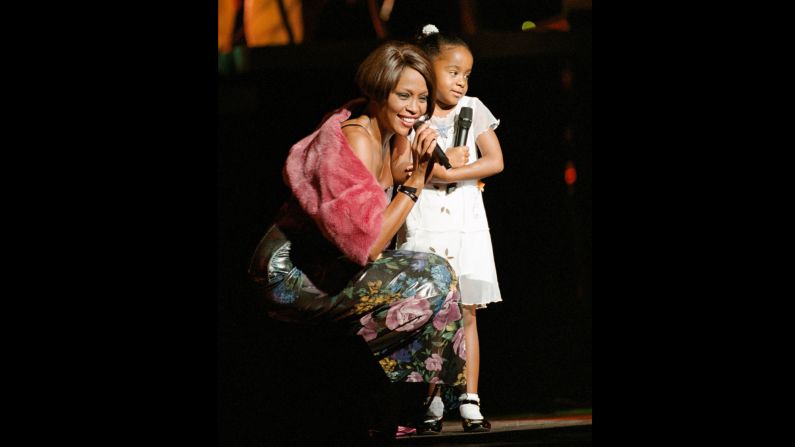

The family of Bobbi Kristina Brown, the 22-year-old daughter of Bobby Brown and the late Whitney Houston, had to make these decisions when she was found unconscious in a bathtub in January. Bobbi Kristina was moved into an Atlanta-area hospice facility in June. She died on July 26, a representative of the Houston family said in a statement.

In most cases, patients and their families have the benefit of time, often years, to plan for their last months of life and whether hospice care is right for them, Radulovic said.

Hospice care focuses on pain relief and symptom control for patients, usually in their own home. “The goal is really to help people get home,” which is where seven out of 10 Americans say they would prefer to die, Radulovic said. The hospice team, which includes doctors, nurses, social workers and other health care professionals, also provides support for their family and caregivers.

Research backs up the benefits of hospice. One study found that talking about end-of-life care with doctors led to earlier patient enrollment in hospice, which in turn was associated with better quality of life. “These discussions improve outcomes and do not hamper hope,” Radulovic said.

Hospice can help anyone with a life-limiting disease

Anyone can get hospice care if they have a terminal illness and their doctors think they will not live more than six months without life-prolonging medicine, the treatments that keep patients alive but do not cure them.

Although the program treated mostly cancer patients in its early days in the 1970s, the majority (64%) of its patients today have a non-cancer terminal illness, such as dementia, heart disease, lung disease or other life-limiting medical conditions. The program cares for people of all ages. A doctor needs to certify that a patient qualifies for hospice care.

Hospice puts no clock on the length of care.

If a patient lives longer than the six months their doctors expected, they can keep receiving hospice care. As long as they still have a terminal illness, and their prognosis is still six months or less, they would not get kicked out of the program. However, if a patient’s condition improves, they may no longer be eligible.

Hospice patients usually pay nothing

Hospice care is usually completely covered by Medicare, Medicaid and private insurance, Radulovic said. Some hospice programs ask for a $5 co-pay for medications but most do not, he added.

For the minority of Americans who do not have health insurance, “most hospice programs won’t turn anyone away,” Radulovic said, adding that these programs cover uninsured patients through donations from the community.

Hospice is not just for the brink of death

Although hospice is designed to help patients in their last months of life, many die shortly after they enter the program and only get days of support. A third of hospice patients die or are discharged within a week of being admitted into the program, Radulovic said. “When you only have care for a couple of days, it is hard for the patient and their family to benefit fully,” he said. Patients are usually discharged because they want to live with family in another area or their condition stabilizes, Radulovic said.

Hospice is everywhere in the United States

The number of hospice programs in the United States has been on the rise since the country’s first program started in 1974. There were 5,800 programs as of 2013. Patients and their family can find a program near them through the Moments of Life website, a public awareness campaign led by the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, or by calling the organization’s help line at 800-658-8898.

“Hospice is pretty much everywhere,” Radulovic said. “Just about every community in the country probably has availability, even in rural areas.”

Hospice is a British transplant

Hospice was the term for a shelter for tired or sick travelers in Medieval times, but the modern concept dates back to 1948 when a physician named Dame Cicely Saunders opened St. Christopher’s Hospice for terminally ill patients in suburban London.

Two decades later, Saunders introduced hospice to the United States when she gave a lecture at the Yale School of Nursing that inspired Florence Wald, then dean of the Yale school, to travel to the London hospice to learn all about it. In 1974, Wald opened the first hospice program in the United States in Branford, Connecticut. It took off quickly after that. By the end of the 1970s, there were community hospices all over the country, Radulovic said.

Hospice in the U.S. and Africa focuses on care at home

Although hospice programs in the United States often care for patients in their own home, programs abroad, especially in Europe, tend to work within hospitals or facilities, just like St. Christopher’s Hospice in London, possibly because it is less complicated than bringing all the necessary medications to a patient’s home, Radulovic said. “The U.S. model of hospice really comes to the patient wherever they are,” he said.

There are some countries where home-based hospice care is the norm, like in the United States. In Sub-Saharan Africa, hospice programs also go to the patient’s home, largely because there are not enough medical facilities to house them, Radulovic said.

Hospice in the U.S. relies on volunteers

Another aspect of hospice in the United States that sets it apart from its counterparts abroad is that 5% of hospice services must be carried out by trained volunteers. The rest of the services are provided by nurses, doctors, social workers, therapists and the many other health care professionals who make up the care team.

“[Volunteers] spend time with the patient, not necessarily doing clinical things, but they might read to them or provide companionship or give respite care so the spouse can get out of the house and get a break,” Radulovic said.

The 5% requirement is part of Medicare guidelines for all hospice programs that get Medicare reimbursement, which is the majority of them. “This harkens back to the foundation of hospice in the country when it was volunteer-driven,” Radulovic said.

Hospice eases the pain

The hospice team puts pain relief above all else for the patient, and doctors and nurse practitioners in the patient’s team prescribe pain medications. Care does not include treatments to try to prolong a patient’s life or to hasten their death. “To get into hospice you have to acknowledge that a cure isn’t possible but any treatment that is palliative in nature is fair game,” Radulovic said.

Hospice cares for the caregivers

One of the things that distinguishes hospice from other palliative care programs is that hospice also cares for family, friends and other caregivers, giving them support, counseling, comfort and education about their loved one, Radulovic said.

After the patient dies, the care can continue in the form of counseling services. “The hospice bereavement team would be there to help. [They] can hopefully offer support whether it is something that is a spiritual problem or a family dynamic issue,” Radulovic said.