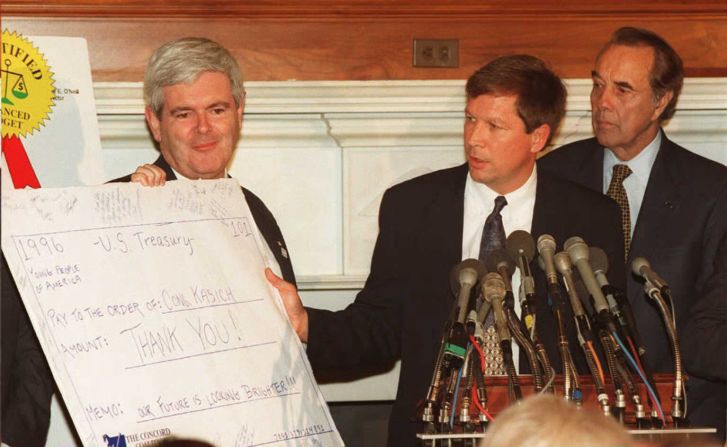

Ohio Gov. John Kasich loves talking about his record in office, his knack for balancing the budget and his controversial decision to back Medicaid expansion.

But there’s one part of his resume he’s less inclined to discuss: the years he spent as a senior executive at Lehman Brothers.

Kasich joined Lehman’s investment banking division as managing director in 2001, working there until the firm’s collapse in September 2008 unleashed global panic and served as the catalyst for the financial crisis.

The Republican governor’s past work at arguably the most deeply vilified Wall Street firm – so despised that in the aftermath of the crisis, some people referred to the bank simply as the “L word” – is likely to serve as rich fodder for political attacks if Kasich were to become a serious contender for the GOP’s presidential nomination. His banking background is particularly ripe for scrutiny and criticism in the 2016 cycle, as populist, anti-Wall Street sentiment is fueling support for a number of candidates on both sides of the political aisle.

Lehman is back in the news with its disgraced former CEO, Richard Fuld, ending his years of silence with unapologetic and at times feisty remarks (“Why don’t you bite me?” Fuld replied when a moderator at a conference in New York asked why he didn’t simply ride into the sunset after Lehman’s fall).

READ: John Kasich says he sees room for 2016 bid due to Bush weakness

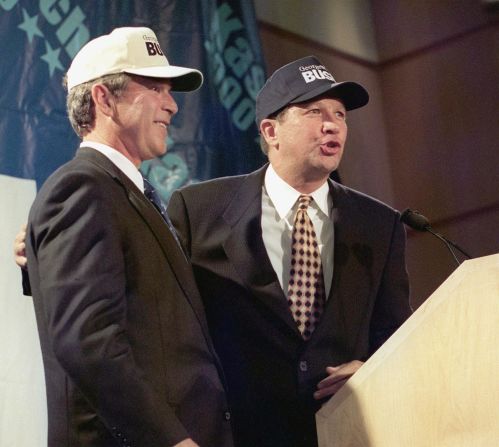

While Kasich has not yet made a decision on 2016 and is barely registering in national polls, the former congressman of 18 years is nevertheless viewed as a potentially formidable candidate because of his deep familiarity with the workings of Washington and his stature as the governor of a critical swing state. Wall Street watchdogs are already on high alert.

“Kasich’s close ties to Wall Street should raise concerns for everyone who suffered due to the collapse of our financial system caused by those very same banks,” said Craig Holman of the advocacy group Public Citizen. “This is not a responsible businessman, and strongly suggests he would not be a responsible president.”

Kasich spokesman Chris Schrimpf said Kasich’s tenure at Lehman gave him critical firsthand experience of the dark side of unchecked “Wall Street ambition.”

“He learned how good businesses make decisions and what it takes for job creators to be successful,” Schrimpf told CNN in a statement. “Attempts to somehow use this experience against him failed miserably six years ago.”

Kasich has practice fielding the Lehman backlash.

In the 2010 gubernatorial race, then-sitting Democratic Gov. Ted Strickland seized on Kasich’s time at the bank, casting it as a distasteful and questionable part of his GOP challenger’s private sector experience.

Strickland and his Democratic allies homed in on the hundreds of thousands of dollars that Kasich made in bonuses on top of his salary. They accused Kasich of lining his own pockets while everyday Ohioans saw their retirement savings and pensions go down the drain.

“John Kasich got rich while Ohio seniors lost millions,” one attack ad said.

Kasich’s defense at the time was that he was based in a two-man office in Columbus, Ohio, and one of some 700 managing directors at Lehman – hardly responsible for the reckless decisions that led the firm to declare bankruptcy.

In an election cycle that handed the Republican Party sweeping victories across the country, the assault on Kasich’s tenure at Lehman ultimately wasn’t enough to help Strickland fend off his challenger.

To this day, Kasich supporters point to the governor’s victory in 2010 as proof the Lehman attacks didn’t work then – and wouldn’t work in 2016.

“His opponents in 2010 threw everything including the kitchen sink at him to try to make a false issue stick,” said Doug Preisse, chairman of the Franklin County Republican Party and a veteran Kasich ally. “To try to say that somebody working out of a two-man office in Ohio bankrupted the country – people laughed at it then, and I think people will laugh at the charge again.”

READ: Can conservatives find their footing in Hollywood in 2016?

But even as the country has taken significant strides since the financial crisis and the economy is finally starting to show signs of a real comeback, Wall Street nevertheless remains a favorite political punching bag.

In the last presidential election, Mitt Romney, the GOP’s nominee, was a victim of the widespread anti-Wall Street sentiment that lingered from the 2008 financial crisis.

President Barack Obama and his campaign seized on Romney’s work at the private equity firm Bain Capital, highlighting specific companies that shuttered and laid off employees under Bain’s watch.

Matt McDonald of Hamilton Place Strategies, who worked on Bain-related messaging for Romney’s campaign, said the 2012 race underscored just how difficult it is to clarify misconceptions about complicated business and financial transactions.

“These candidates are going to have to figure out a good, quick answer on what their role was, what they did, and how they account for their time during the financial crisis,” McDonald said of Kasich and any other GOP candidates with ties to Wall Street. “Kasich wasn’t trading residential mortgage backed securities in New York. That’s not what he was doing.”

(Jeb Bush has also advised Lehman, and Chris Christie lobbied on behalf of the securities industry before going into public office.)

Some of the most fierce attacks against Kasich’s time at Lehman could come from the other side of the political aisle.

Heading into 2016, former Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders – who are challenging former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton for the Democratic nomination for president – are both advocating for tough Wall Street regulations and vowing to promote policies to rein in the big banks.

O’Malley, who launched his presidential campaign May 30, used particularly aggressive language against what he called the “bullies of Wall Street” in his announcement speech, even singling out Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein.

“What you’re hearing from Martin O’Malley and Bernie Sanders on our side of the aisle” will help attract attention to Kasich’s Lehman background, said Chris Redfern, the Ohio Democratic Party’s former chairman. “He’s going to get questions that he will find difficult to answer.”

Ray Glendening, who served as senior strategist at the Democratic Governors Association during Kasich’s first campaign for governor, said Kasich is likely to experience scrutiny over tenure at Lehman as his candidacy for president picks up momentum.

“People that are not even really dialed into political stories, they know what Lehman is,” Glendening said. “Because he’s running for the highest office in the land, he’s going to have some explaining to do.”