Story highlights

Most 2016 GOP candidates support a ban on abortions after 20 weeks, while Democrat Hillary Clinton has spoken against it

So far 14 states have barred the procedure after 20 weeks, though court orders have kept some from putting their bans into effect

As the technician scanned her belly to determine the gender of her baby, Christy Zink could not have been more excited about her pregnancy.

At 21 weeks, the pregnancy had been going well. But the look on the technician’s face as she examined the images told Zink that was no longer the case.

Further scans revealed that the fetus’ brain was badly malformed. Two hemispheres should have formed by then, but the right side of the brain had not developed at all.

The prognosis left Zink, a writing professor at Georgetown University who was then 39, and her husband with a terrible choice: carry the baby to term and raise a child who would be in constant pain, need to be hooked up to life-sustaining machines and would require permanent hospitalization.

Or have an abortion. Since she was 21 weeks pregnant and could only find a doctor willing to perform abortions up to 22 weeks, she and her husband had a week to decide.

“It was the hardest decision that my husband and I ever had to make,” Zink recalled in a recent interview, six years after they opted to end the pregnancy.

Women like Zink are at the center of the newest front in the abortion war as Republicans push for a ban on such procedures after a pregnancy reaches 20 weeks.

2016 candidates weigh in

The U.S. House approved a bill in May that would establish such a standard and similar measures have passed in 14 states. The limit is becoming an issue on the 2016 campaign trail, with nearly all the GOP presidential hopefuls backing it and Democrat Hillary Clinton slamming it.

Both sides of the abortion debate say the push for a ban after 20 weeks opens up a new legal debate over the procedure that may well find its way to the Supreme Court.

Abortion rights advocates say the measures are a direct challenge to high court cases establishing that women have an unfettered right to an abortion before the point of viability, generally thought to be at 24 weeks. But abortion opponents think they can succeed by arguing the fetus is able to feel pain at 20 weeks, a hotly contested idea.

“We feel that once the child can feel pain, we think the court will say the state does have an interest in protecting the unborn child,” said Carol Tobias, president of the National Right to Life Committee.

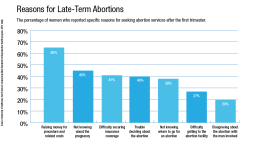

About 1.2% of the slightly more than 1 million abortions that are done annually take place after 21 weeks, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a pro-abortion rights research organization whose statistical work is widely considered reliable. One study determined that 80% of this 1.2% could be described as dealing with issues other than medical concerns like Zink’s, such as having a history of substance abuse or having trouble finding an abortion provider.

Poor women most affected

These are largely poor women who lack private health insurance and who don’t live in one of the 17 states that allow Medicaid to pay for abortions under some circumstances.

Researchers say a prime cause of women seeking abortions during their second trimester – the second 13-week period in a 39-week gestation – is that they find out relatively late that they are pregnant.

“The later a woman is in pregnancy, the harder it is to access abortion services because there are fewer providers, they’re farther away and the procedures cost more,” said Diana Greene Foster, an associate professor at the University of California, San Francisco who conducted one of the few studies of women who seek abortions after the first trimester.

“Wealthier women are able to access this care; poor and middle-class women are more likely to show up at an abortion clinic beyond the gestational limit and be denied an abortion,” she said.

Overall, the UCSF study of 441 women found that those who had second-trimester abortions did not vary from those who had first-trimester abortions along the lines of race, ethnicity, mental or physical health or rates of substance abuse. But in addition to being more likely to have discovered they were pregnant later on, women seeking these abortions did tend to be younger, need to travel more than three hours to an abortion clinic and lack private health insurance.

READ: Scott Walker: I would sign 20-week abortion ban

Once women discover they’re pregnant, the leading reason for postponing an abortion is lack of money. In the UCSF study, conducted by the Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health program at the School of Medicine in 2013, 65% of the women who had second-trimester abortions cited “raising money for the procedure and related cost” as the reason they delayed terminating their pregnancies.

The cost of abortions escalates rapidly the later the procedure is conducted. The average cost to terminate a pregnancy at 12 weeks is $500, according to the National Abortion Federation, the trade association for abortion clinics. At 16 to 18 weeks, the price jumps to about $1,000. After 20 weeks it doubles again to $2,000.

Some poor women spend weeks scraping together enough money to get an abortion, only to find out that in that time, the goal has moved further from their grasp, It’s a vicious cycle that ends with procedures later in their terms, according to abortion rights advocates.

This poor population tends to lack political clout, which abortion rights advocates say contributes to an absence of public outcry over such bans.

“These are not the folks that the public rallies around,” said Jennifer Dalven, director of the ACLU’s Reproductive Freedom Project. “These are not the folks that people are likely to go to the mat for. That’s true with abortion. But it’s also true across our society.”

Widespread public support for ban

Bans on abortions at later stages of pregnancy enjoy widespread public support. A Washington Post poll in 2013 found that 56% of Americans supported a ban after 20 weeks.

Republicans who back the prohibition see these bans as a means of harnessing public support for abortion restrictions, which they often back out of religious conviction.

“We are focused on where there is common ground,” said Mallory Quigley, communications director for the Susan B. Anthony List, which supports candidates who oppose abortion. “This is something the other side has been saying for years – that we need to find common ground. Well, if you look at the polls on this bill, this is where the country is at.”

Yet the majority of the country also supports Roe v. Wade, the 1973 Supreme Court ruling that legalized abortion nationwide. According to a 2013 Gallup Poll, 53% of Americans didn’t want the decision overturned.

Constitutional fight brews

Dalven said the 20-week abortion ban takes direct aim at one of the central tenets of Roe, which was affirmed in the high court’s 1992 Planned Parenthood v. Casey decision.

“These laws are directly in conflict with what Roe and Casey said. That you can’t ban abortion before viability,” said Dalven. “As a constitutional matter, that’s why the issue is really important.”

In their fight to influence public attitudes, the sides have found themselves battling over the use of the letter “R.”

Anti-abortion organizations tend to describe procedures to end pregnancy at 20 weeks as “late-term” abortions, a means of associating them with horrors such as the work of Kermit Gosnell, a Philadelphia doctor who performed abortions on women up to seven or eight months pregnant and was convicted of killing a baby born alive in a botched abortion.

Pro-abortion rights groups favor calling 20-week abortions “later-term,” saying that, while they occur further along in the pregnancy than the typical abortion, they still only take place at around the midpoint of a normal pregnancy.

There is even a dispute as to when to start counting the weeks. The bill that passed the House bans abortions 20 weeks after fertilization. However, many medical professionals and organizations, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, generally measure pregnancies starting from the first day of the mother’s last menstrual cycle.

The trend toward barring abortions after 20 weeks has been picking up steam since Nebraska in 2010 became the first state to prohibit the procedure. To date, 14 states have enacted similar legislation, though some have been stayed by court orders from putting their bans into effect.

The Nebraska law, like most of the others, only allows exemptions in the case of medical emergencies, the imminent death of the mother or if continuing the pregnancy runs the risk of “substantial and irreversible physical impairment of a major bodily function.”

The measure that recently passed the House was the brainchild of a lawyer at the National Right to Life Committee in Washington who felt that, after a 2007 Supreme Court ruling upholding a federal law banning a procedure known as “partial-birth abortion,” the justices would look more favorably on arguments based on the interests of the fetus.

The rare procedure, known medically as intact dilation and extraction, is usually performed on women who are 19 to 26 weeks pregnant. The procedure has been defended by many doctors as medically necessary in certain cases, but Congress banned it in 2003 and the Supreme Court upheld the law in 2007.

“The partial-birth abortion ban put the baby back into the center of the debate,” said Julie Schmit-Albin, executive director of Nebraska Right to Life. “It was a sea change.”

Can a 20-week-old fetus feel pain?

One key to the 20-week ban effort is the issue of whether – and when – a fetus is capable of feeling pain.

Proponents base their assertions on the work of pediatrician Kanwaljeet S. Anand, whose extensive research on the development of fetal pain and stress led him to conclude in 2004 that “the human fetus possesses the ability to experience pain from 20 weeks of gestation, if not earlier.”

Other studies, however, have challenged his assessment that fetuses from 16 weeks on that undergo surgery produce increased levels of stress hormones and heavier blood flow to the brain – reactions that are associated with pain.

They say the necessary nerve connections have not completely formed by then and that the fetal reactions are reflexive and similar to those of brain-dead people.

Supporters of the ban also point to medical advances that are moving up the moment when a fetus can live outside its mother’s uterus. They believe these developments will change public perceptions of when to begin to protect fetuses.

READ: House passes bill banning abortions after 20 weeks

A recent study in the New England Journal of Medicine reported that around 23% of babies born as early as 22 weeks into a pregnancy survived.

Anti-abortion advocates believe the viability threshold may be pushed to an even earlier stage in the future.

“Technology is on our side,” said Tobias, the National Right to Life president.

But for Christy Zink, technology couldn’t do enough for her child.

“What we knew and what we sensed was that after the birth, it could get worse and worse,” Zink said. “In fact, his dying was almost less scary than his living.”

She concluded, “To have a child so close to death and in so much pain all of the time, I felt that that’s no life at all.”

CORRECTIONS: An earlier version of this story erroneously stated that 20% of women who seek to terminate their pregnancies after 21 weeks did so because of health or fetal complications. One study determined that 80% of women getting these abortions faced non-medical concerns such as substance abuse or trouble finding an abortion provider.

Additionally, the story quoted obstetrics expert Hal C. Lawrence as saying a New England Journal of Medicine study found that 5% of babies born during the 22nd week of pregnancy survived after intensive care. The actual figure is around 23%.