Story highlights

Liberia has gone without a new case for 42 days, twice the maximum incubation period

"The road to zero has been long and hard," says Dr. Thomas Frieden, director of the CDC

Guinea and Sierra Leone each had nine new cases last week

After losing more than 4,000 people to Ebola, Liberia has now been declared free of the disease by the World Health Organization (WHO).

I wish I were there to hug the wonderful people I met when I visited at the height of the epidemic in September, when any contact, even shaking hands, was forbidden.

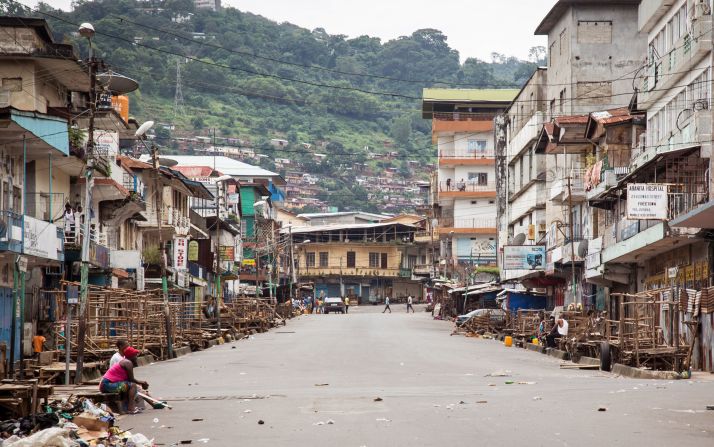

It was a horrible time. Ebola patients stood in line to get into hospitals that didn’t have a bed to spare. Thousands of children in West Africa were orphaned. Burial teams roamed the streets carrying victims to crematoriums.

“We went through just a horrific epidemic,” said Dr. Thomas Frieden, director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, who visited the country in August. “It’s a searing memory that many of us will carry with us for the rest of our lives.”

Something else is seared in my mind, too: the realization that smart people failed to stop this epidemic before it got so terribly out of hand. The outbreak started in March, and when I arrived six months later, the response was still clumsy.

Officials in Monrovia, including ones from the WHO, held an elaborate opening ceremony for an Ebola hospital, but then a few hours later when patients arrived, no one came out to help them. Weakened by the virus, the patients fell out of ambulances onto the ground.

A doctor in a rural county begged authorities for an Ebola hospital, but no help arrived. He was forced to build one himself, where he managed to save many patients.

In another part of Liberia, a woman couldn’t find space in the hospital for her four Ebola-stricken relatives and was forced to take care of them at home by herself. She had no protective gear, and so suited up in trash bags to keep herself safe. Why was gear unavailable? It was just one of many unanswered questions during my time there.

Larry Gostin, faculty director of the O’Neill Institute for National & Global Health Law at Georgetown University, gives the world an “F” for the initial response to Ebola.

“If the world had mobilized rapidly and decisively, we could have saved 10,000 lives, great human hardship, and enormous health and social costs in three of the poorest countries in the world,” he wrote CNN.

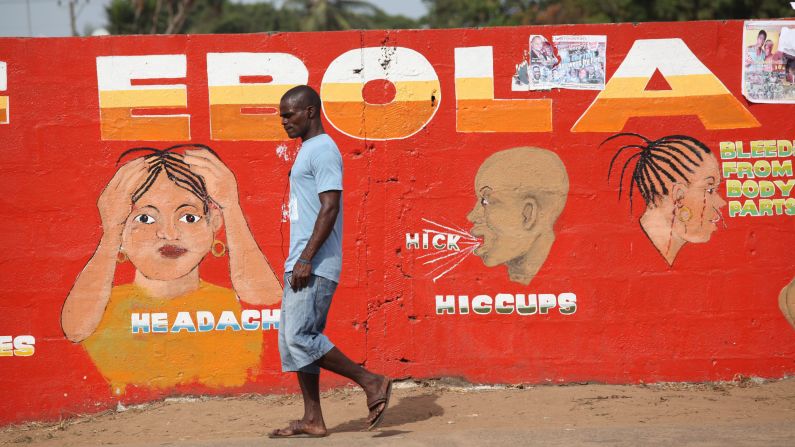

Three reasons are often given for this poor initial response: Ebola hit big cities, where people live in close quarters; the West African countries have a dangerous lack of doctors, nurses, laboratories and supplies; and it was difficult to convince people to put a halt to the tradition of washing their dead relatives before burial, which spread the virus.

While all of those are true, there was something else going on.

Frieden describes how back in March of last year, he tried to get his teams into Guinea, where the outbreak started, but he says WHO leaders there wouldn’t let them in.

“We got all these crazy questions, like ‘We’re not sure your team is qualified, send us more CVs,’ and ‘We’re not sure when would be a convenient time for you to come,’” he said.

Frieden Intervened, calling WHO officials in headquarters in Geneva. “That’s really unusual, for me, at my level, to have to call and say, ‘Let my staff in,’” he said. “There’s been maybe one other instance where I had to do that in my six years as director of the CDC.”

In July, the CDC was allowed to ramp up the response, sending 50 staffers in just 10 days and 100 total by the end of the month.

“But our team was not particularly welcome there,” he said. “It was not a very comfortable situation.”

The problem, he says, was that WHO leaders in Africa failed to appreciate the severity of the outbreak and were overconfident they could handle it on their own. “We were surging into the area and the WHO said, ‘We don’t need you,’” he said.

As those issues resolved in the late summer and fall, the CDC and others could move in and do their jobs. Gostin gives this “late, belated response” an “A.”

It eventually worked. Liberia has gone without a new case for 42 days, twice the maximum incubation period, which is why it’s now deemed free of Ebola.

“The road to zero has been long and hard,” Frieden said.

Guinea and Sierra Leone each had nine new cases last week, a dramatic decline from last fall when each week saw hundreds of new cases.

There’s currently an internal and external review of the WHO Ebola response. “What WHO did or did not do will be examined by this commission and the results will be made publicly available for all to see,” said WHO spokesman Tarik Jasarevic. “In parallel, we are currently undergoing an independent evaluation of our response chaired by Dame Barbara Stocking.”

And the organization is already making reforms to respond more rapidly and effectively to public health emergencies. “We have an extensive program of work to implement these changes and will be reporting to the World Health Assembly later this month,” Jasarevic wrote CNN.

But Gostin is concerned WHO won’t do enough.

“I believe firmly that the world remains unprepared for the next epidemic,” he wrote to CNN. “The next epidemic, moreover, could be far worse than Ebola, and we are not well prepared.”