Editor’s Note: Charles Kaiser is the author of the upcoming book “The Cost of Courage,” from which this was adapted from. The views expressed are his own.

Story highlights

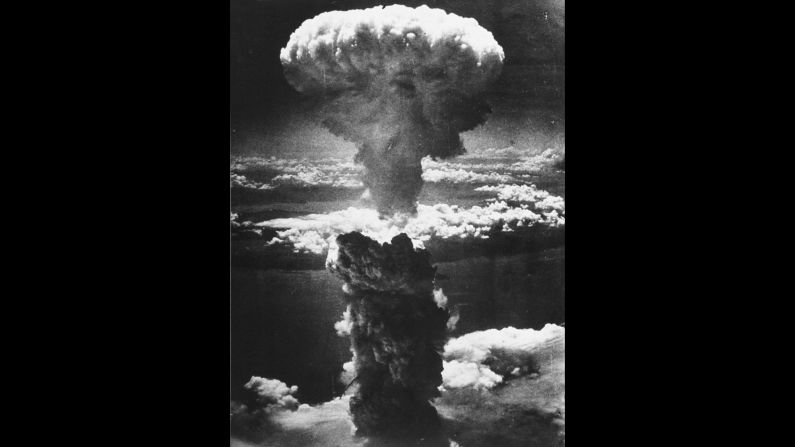

Friday marks the 70th anniversary of V-E Day

Charles Kaiser: U.S. view of resistance hopelessly naive

Had all of us in France meekly, lawfully carried out the orders of the German master, no Frenchman could have ever looked another man in the face. Such submission would have saved the lives of many – some very dear to me – but France would have lost its soul.

– Commandant le Baron de Vomécourt

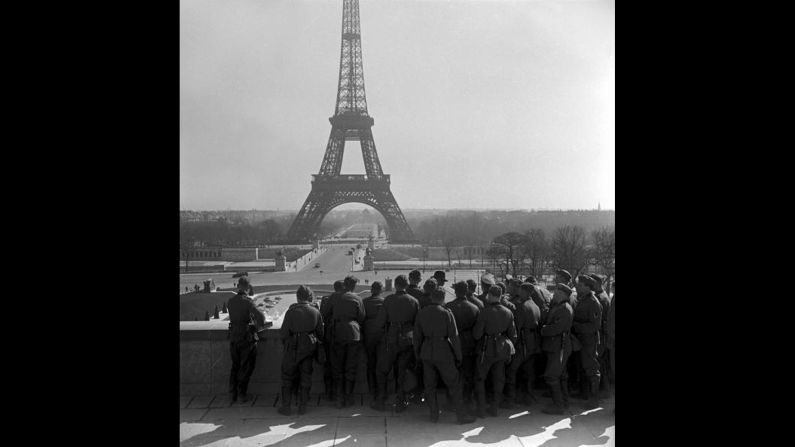

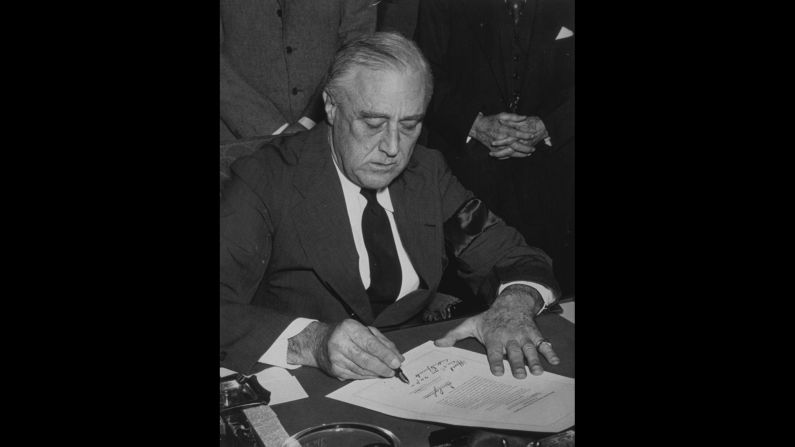

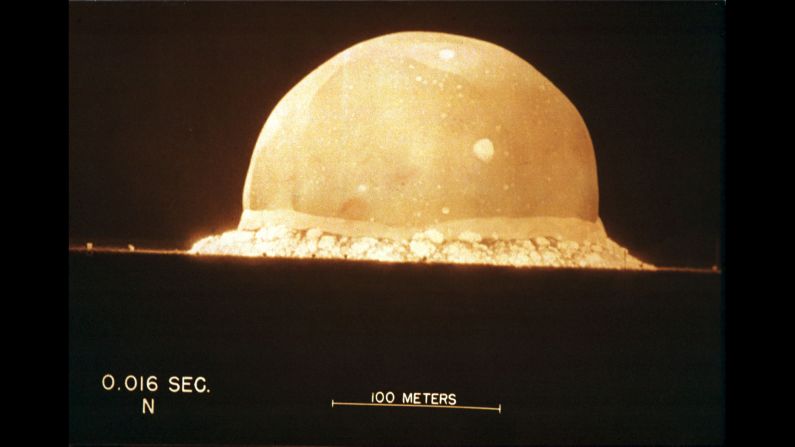

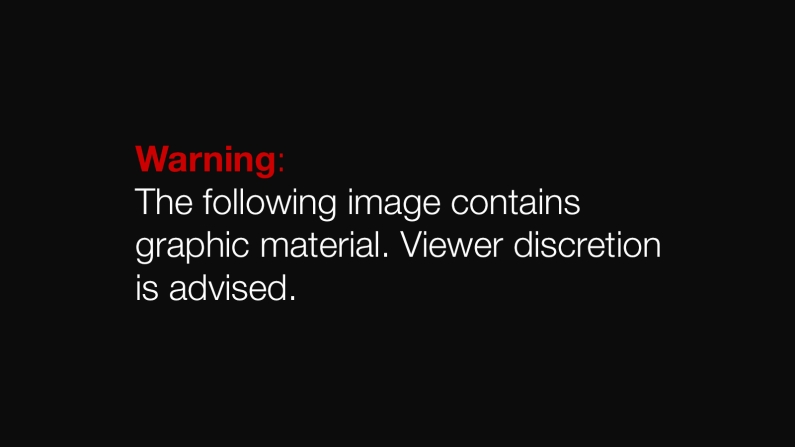

This Friday, Europe will mark the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II in Europe, the moment when the “Thousand-Year” German Reich was finally extinguished, after the continent had endured 12 years, four months and eight days of Nazi mayhem, perversity, destruction and death.

Americans will remember the heroic sacrifices of our troops, from Anzio and Normandy to the Battle of the Bulge, and once again we will congratulate ourselves for the crucial role we played in the liberation of Paris in summer 1944.

What almost no one in America will recall is the crucial role the French Resistance played in the liberation of France, or the gratitude Dwight Eisenhower expressed, over and over again, for the vital contribution these French men and women made to the success of the Allies at Normandy.

The dismissiveness of Americans never ceases to exasperate me. “Was there one?” That was the question I was asked most often – even by intelligent people – whenever I mentioned that I was writing about the French Resistance. Yet having for years immersed myself in the details of the French Resistance movement – and the extraordinary heroism of one French family in particular – the answer to that smug question is clear.

The subjects of my book, André, Christiane and Jacqueline Boulloche, were three siblings who joined the Resistance soon after the occupation began. They were bourgeois Catholics and André was a French civil servant, which made them quite unusual for early members of the rebellion. André Postel-Vinay, another civil servant and the man who recruited André Boulloche into the Resistance at the end of 1940, explained their decision to me this way: “For us, the Resistance was a kind of lifesaver – because without it, life no longer had any meaning.”

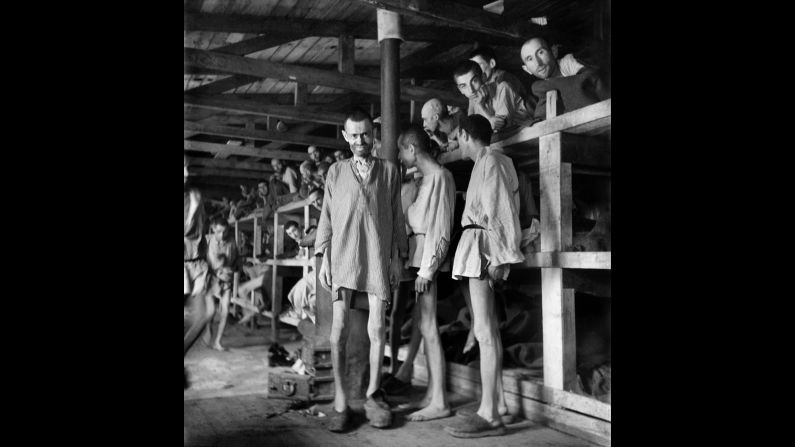

Christiane, Jacqueline and André all survived the war, although André was arrested and shot by the Gestapo in January 1944, and endured imprisonment at Auschwitz and two other concentration camps. But the cost of their courage to the rest of their family was so great that they did not talk about what they had done during the war for more than half a century.

It is this kind of heroism that Dwight Eisenhower pays tribute in his memoir, “Crusade in Europe.”

Now of course it is true that France capitulated with spectacular speed in the face of the German invasion in May 1940. As the Germans swept through France, Marshal Henri-Philippe Pétain, the 84-year-old hero of World War I who had been summoned out of retirement, led the fight against an offer from British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to merge France and the United Kingdom into an “indissoluble” Franco-British union to continue the war against the Germans together. A French minister of state declared “Better to be a Nazi province. At least we know what that means” – and less than a week later, France and Germany signed an armistice in Compiègne.

The Vichy government then engaged in massive collaboration with the Germans. Indeed, there was enthusiastic French participation in the “final solution,” including the arrest of 4,051 Jewish children in Paris in summer 1942 – even though the Germans had not asked the French to arrest anyone younger than 16.

But most Frenchmen were neither collaborators nor resisters; they just kept their heads down and tried to get enough to eat, which was extremely difficult in Paris, where citizens suffered with near-starvation rations.

As Columbia University historian István Deák writes in a brilliant new book, “Europe on Trial,” there were people throughout Nazi-occupied Europe “who wished to remain nonpolitical. For them, both collaboration and resistance were unwelcome, even threatening activities. For many if not most Europeans, the collaborator was a wild-eyed fanatic who tried to get your son to join the Waffen SS … or to work in a German factory, while the resister was yet another fanatic, likely to be a ragged and unappetizing foreigner who sabotaged train travel and wanted your son to go to the forest and risk being killed there by the Germans.”

Opinion: ‘The scoop from hell’

Americans reflexively believe that had Germany occupied the United States, nearly all of us would have joined an armed resistance to the Nazis. That’s what I thought, too, when I was 16. But that reflects a hopelessly naive view, both of what the world looked like to most people after the Nazis had conquered Austria, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg, Denmark, Norway and France, and of what it actually meant to take up arms against an occupying power.

Robert Paxton is the dean of American historians of the occupation of France. No one has done more than he has to expose the depth of French collaboration with the Nazis. But in his classic book, “Vichy France,” Paxton also writes “an American reader who honestly recreates the way the world looked from France (in 1940) cannot assume that he or she would easily have found the path to a 1944 hero’s role.”

And Deák reminds us what it really meant to be a member of the Resistance: “To resist meant to leave the legal path and to act as a criminal. … In order to be able to print and distribute illegal newspapers, one had to steal strictly controlled printing paper and machines and to forge or steal ration cards, banknotes, residence permits and identity cards. To fight the enemy the resisters needed to seize arms from military garrisons or from rival resisters. All this required the talents of a burglar, a forger and a thief.”

The French Resistance undertook nearly 1,000 acts of sabotage in the hours after the Normandy invasion began, and the damage they inflicted on railroads and other communications played a crucial role in preventing German reinforcements from arriving quickly in Northern France. And every time a German troop train was sabotaged, a nearby French village was likely to suffer horrendous retaliation – like the town of Tulle, where a hundred men where seized at random and massacred three days after the Normandy invasion, or the village of Oradour-sur-Glane, where 642 citizens, including 205 children, were killed the day after that. The men were shot; the women and children were burned to death in a church.

“We were depending on considerable assistance from the insurrectionists in France,” Eisenhower remembered. “Throughout France the Free French had been of inestimable value in the campaign. … Without their great assistance the liberation of France and the defeat of the enemy in Western Europe would have consumed a much longer time and meant greater losses to ourselves.”

Marcel Ophuls, who directed “The Sorrow and the Pity,” the landmark documentary about the German occupation of France, was the other man (together with Robert Paxton) who did the most in the 1970s to expose the extent of French collaboration during the war. But like Paxton he refuses to judge the French harshly. When I interviewed Ophuls, I quoted what British Prime Minister Anthony Eden had said to Ophuls in “The Sorrow and The Pity”: “If one hasn’t been through … the horror of an occupation by a foreign power, you have no right to pronounce upon what a country does which has been through all that.”

Was that also the filmmaker’s opinion?

“I think that’s why I put it there,” Opulus replied. “It seems sort of pretentious to use Anthony Eden as a spokesman, but he is expressing my sentiments there. I’m glad that it made an impression on you.”

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.