Story highlights

Researchers say a medieval remedy made of garlic, onion, wine, bile may be able to defeat MRSA superbug

Ancient recipe was found in 10th-century medical book at the British Library

It might sound like a really old wives’ tale, but a thousand-year-old Anglo-Saxon potion for eye infections may hold the key to wiping out the modern-day superbug MRSA, according to new research.

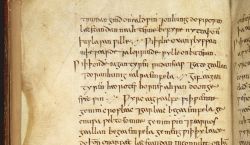

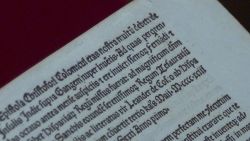

The 10th-century “eyesalve” remedy was discovered at the British Library in a leather-bound volume of Bald’s Leechbook, widely considered to be one of the earliest known medical textbooks.

Christina Lee, an expert on Anglo-Saxon society from the School of English at the University of Nottingham, translated the ancient manuscript despite some ambiguities in the text.

“We chose this recipe in Bald’s Leechbook because it contains ingredients such as garlic that are currently investigated by other researchers on their potential antibiotic effectiveness,” Lee said in a video posted on the university’s website.

“And so we looked at a recipe that is fairly straightforward. It’s also a recipe where we are told it’s the ‘best of leechdoms’ – how could you not test that? So we were curious.”

Lee enlisted the help of the university’s microbiologists to see if the remedy actually worked.

The recipe calls for two species of Allium (garlic and onion or leek), wine and oxgall (bile from a cow’s stomach) to be brewed in a brass vessel.

“We recreated the recipe as faithfully as we could. The Bald gives very precise instructions for the ratio of different ingredients and for the way they should be combined before use, so we tried to follow that as closely as possible,” said microbiologist Freya Harrison, who led the work in the lab at the School of Life Sciences.

The book included an instruction for the recipe to be left to stand for nine days before being strained through a cloth. Efforts to replicate the recipe exactly included finding wine from a vineyard known to have existed in the ninth century, according to Steve Diggle, an associate professor of sociomicrobiology, who also worked on the project.

The researchers then tested their recipe on cultures of MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, a type of staph bacterium that does not respond to commonly used antibiotic treatments.

The scientists weren’t holding out much hope that it would work – but they were astonished by the lab results.

“What we found was very interesting – we found that Bald’s eyesalve is incredibly potent as an anti-Staphylococcal antibiotic in this context,” Harrison said.

“We were going from a mature, established population of a few billion cells, all stuck together in this highly protected biofilm coat, to really just a few thousand cells left alive. This is a massive, massive killing ability.”

Diggle said the team also asked collaborators in the U.S. to test the recipe using an “in vivo” wound model – meaning it’s in a live organism – “and basically the big surprise was that it seems to be more effective than conventional antibiotic treatment.”

The scientists were worried they wouldn’t be able to repeat the feat. But three more batches, made from scratch each time, have yielded the same results, Harrison said, and the salve appears to retain its potency for a long time after being stored in bottles in the refrigerator.

The team says it now has good, replicated data showing that the medicine kills up to 90% of MRSA bacteria in “in vivo” wound biopsies from mice.

Harrison says the researchers are still not completely sure how it works, but they have a few ideas – namely, that there might be several active components in the mixture that work to attack the bacterial cells on different fronts, making it very hard for them to resist; or that by combining the ingredients and leaving them to steep in alcohol, a new, more potent bacteria-fighting molecule is created in the process.

“I still can’t quite believe how well this 1,000-year-old antibiotic actually seems to be working,” Harrison said. “When we got the first results we were just utterly dumbfounded. We did not see this coming at all.”

She added: “Obviously you can never say with utter certainty that because it works in the lab it’s going to work as an antibiotic, but the potential of this to take on to the next stage and say, ‘yeah, really does it work as an antibiotic’ is just beyond my wildest dreams, to be honest.”

Lee, who translated the text from Old English, believes the discovery could change people’s views of the medieval period as the “Dark Ages.”

“The Middle Ages are often seen as the ‘Dark Ages’ – we use the term ‘medieval’ these days … as pejorative – and I just wanted to do something that explains to me how people in the Middle Ages looked at science,” she said.