Story highlights

The fastest airplane in the world -- an SR-71 spy jet -- has held the record for nearly 40 years

Crew who set the record at 2,193 mph share their stories about the historic flight

America's SR-71 spy jets retired in 1999 after helping win the Cold War

Al Joersz and George Morgan remember the day they joined the ranks of the fastest men alive.

In 1976 they smashed the world aviation speed record by blasting across the Western United States in America’s super spy plane, the Lockheed SR-71.

Official speed: 2,193 mph.

“It wasn’t supposed to be that big of a deal,” Joersz said on the phone from his home in Temple, Texas.

But it’s still kind of a big deal. That was nearly 40 years ago, and their record still stands.

“We knew we were going to be setting some records, but we didn’t look at it as something that would endure this long.”

The two Air Force officers had been picked to fly a special U.S. military demonstration for the World Air Sports Federation, the international group that oversees aviation records.

Morgan, who spoke with CNN by phone from his home in Hoodsport, Washington, said they were lucky to get the assignment. “We didn’t go as fast as we could. We just went as fast as we needed to go to set the record.”

Moving at 2,193 mph may be hard to wrap your head around.

This may help:

• Think about moving more than three times faster than the speed of sound, aka Mach 3.

• Consider this: It’s more than 33 miles per minute.

• Somebody call Superman: Joersz and Morgan literally flew “faster than a speeding bullet.”

Clearly this flying machine was special. In fact, the SR-71 proved itself from the 1960s through the 1990s as an important intelligence tool that helped ease rising U.S.-Soviet tensions during the Cold War.

Spirits were high at California’s Beale Air Force Base on July 28, 1976, as the ground crew buckled Joersz and Morgan into their seats — Joersz, the pilot, in front; Morgan, the reconnaissance officer in charge of surveillance equipment, sitting in a separate cockpit, behind.

They looked like astronauts in their helmets and pressurized flight suits, which were required because the plane flies so high. Joersz recalls that the tanks were almost full — filled with a unique fuel developed especially for the plane’s two huge, powerful engines.

After making final checks of their equipment, Joersz lined up the long, black, ominous aircraft at the end of the runway. Ground crews signaled a green light for departure. Then Joersz put his left hand on the throttle, pushed it forward and aircraft Number 17958 took off.

“We climbed directly to our target altitude right from brake release,” Joersz remembered. Soon they were soaring at 80,600 feet — more than twice the altitude of passenger jets — so high that Joersz remembers seeing the curvature of the Earth.

After leveling off, he shot the plane at full throttle across most of the first pass of the 15kilometer straight-line course.

In the seat behind him, Morgan helped Joersz follow the mission checklist and made sure they remained on track. “I was watching very closely to make sure we were right on the money,” Morgan said. “And we were.”

To break the record, the rules called for Joersz to turn the plane around and repeat the same path at virtually the same altitude. Morgan fed Joersz audio cues alerting him when to change course.

“I powered back … and began the turn — 90 degrees to the left, then a 270-degree turn to the right,” Joersz said. The jet re-entered the course at precisely 80,600 feet. That’s about 15 miles high.

Morgan and Joersz encouraged each other over their headsets, Morgan recalled.” ‘What do you think? Are we gonna make this thing? Oh, yeah, piece of cake!’ “

As Joersz remembers, after flying over four states, they landed safely back at Beale about 55 minutes after they took off.

The plane came to a stop. Joersz and Morgan climbed out of their cockpits and were met by a crowd of VIPs saluting, shaking hands and back-slapping. The celebration included generals, Lockheed executives and a congratulatory phone call with the commander in chief of the Air Force Strategic Air Command.

Per the rules, the official speed was an average of both legs. Final calculations showed that Joersz and Morgan had broken the previous record by 123 mph – set by a similar Air Force spy plane, the YF-12A, in the ’60s.

They actually thought they could do better, hoping for 2,200 mph, said Joersz. “We got pretty close — within 7 mph.”

Superhot

Now, four decades later, the plane Joersz and Morgan flew that day holds court inside a hangar at the Museum of Aviation near Georgia’s Warner Robins Air Force Base.

Stenciled on its towering tail is a white snake and the number 17958. It’s easy to imagine it streaking across the sky that day in 1976.

From tip to tail, the jet shows engineering details that scream speed:

• Dramatically sweeping delta-shaped wings

• Giant, custom made engines that gulped 8,000 gallons of fuel per hour at cruising speed

• Tires that were infused with aluminum powder to ward off temperatures upward of 600 degrees Fahrenheit.

• Quartz-covered cockpit windows, which got so hot from high-speed friction that pilots warmed their in-flight meals by holding their food up to the glass. Despite protection from his pressure suit gloves, “you couldn’t hold your hand up to the glass for more than five seconds without pulling it back due to the heat,” Joersz said.

Planes have flown faster — unofficially — but this is the one that set the official record for a piloted plane powered by an air-breathing engine.

The pressurized flight suits added to “the mystique, the magic, the drama of this airplane,” Joersz said. They also led to awkward moments. The simple act of scratching your nose was made nearly impossible while wearing a helmet. “You figured out a way to do it by turning your head and the helmet and using the mic to scratch your nose,” Joersz said.

‘Bam!’

Despite its speed, piloting the SR-71 didn’t feel the same as flying a fighter jet during air-to-air combat, said Joersz. The plane’s design sacrifices maneuverability for speed and higher altitude. “I definitely wouldn’t call it boring,” he joked. “It’s more intense — rather than a lot of thrashing around.” The plane “wasn’t excruciatingly difficult to fly, it was just challenging. You had to pay a lot of attention and be prepared to handle little things it would throw at you once in a while.”

Those “little things” could be dangerous, like the phenomenon known as “unstarts.”

Unstarts happened when shock waves created by the jet’s incredible speed would suddenly force one engine to lose power, shoving the plane suddenly sideways.

“The plane sucks that shock wave in there,” Morgan said. “It just slams that engine shut. If your helmet hit the left cockpit window — bam! — that meant it was the right engine. That was the key. It happened so fast, you really didn’t have time to look around.”

If the pilot failed to control the unstart, “The nose would pitch up,” said Joersz. “If the pitch up became too extreme, then you could lose the airplane … the airplane would break apart.”

Training for how to handle unstarts “got your heart beating pretty well,” Joersz said. “After a while you kind of got used to them.” Eventually the planes were outfitted with an automatic system that helped pilots manage unstarts.

‘Drip, drip, drip’

Another quirk: The plane was infamous for leaking fuel.

The extreme temperature changes expanded and contracted its fuel tanks. Eventually that created leaks in the sealant where the tanks were joined. “Lockheed changed the sealant composition many times through the years trying to get one that would work better than the last one — trying to solve the issue of the leaks,” Joersz said. “But they never did. It always leaked.”

“It didn’t pour out, but it was leaking — yeah — drip, drip drip,” said Morgan. “But when you get up to speed, the planes kind of seal themselves.”

Spotting a ball 15 miles away

The plane wasn’t just fast. It took pictures. Really, really detailed pictures.

During the Yom Kippur War of 1973, U.S.-Soviet tensions spiked when Israeli forces squared off against the armies of Egypt and Syria. Joersz and Morgan flew missions in separate planes over the region.

“Making a turn, we took a picture of a soccer game which was off to the side about 12-15 miles away and we could see the soccer ball coming off a guy’s foot,” Morgan said. “It wasn’t really perfect, but you could tell the guy was kicking a ball.”

During those tense days, President Richard Nixon moved the alert level for American forces to Defcon 3 — Defense Condition 3 — one step closer to war. The spy planes returned with “photographic information that allowed us to provide a clear picture of how the war was progressing,” Joersz said. “So we helped our national decision makers make wise decisions to do — and not do — particular things.”

Breaking up

Flying and maintaining the SR-71 was expensive. Nonetheless, the aircraft was such a valuable spy tool that Washington had a hard time breaking up with it. It could do things satellites couldn’t.

“Everybody knows when a satellite is coming. They just go hide ‘til the satellite goes away,” Morgan said. “But when the SR shows up, nobody knows it’s there.”

Congress eventually forced the SR-71 into retirement in 1989. But the Pentagon missed it so much, the plane briefly returned to duty in the ’90s. Finally, the last two deployed SR-71s — which NASA was using for research — were put out to pasture in 1999.

Lockheed built only 32 SR-71s. Most of them now live in museums. Number 17958 was delivered to Warner Robins in 1990. It sits next to other military surveillance icons, the Global Hawk and the U2.

Now age 71 and retired, Joersz is confident a new aircraft will someday break the record, perhaps reaching five or even six times the speed of sound. “It’ll make Mach 3 seem pretty slow.”

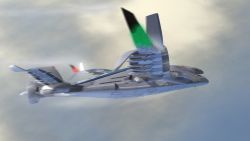

In fact, last December, NASA hired Lockheed to research development of a new hypersonic engine that might power a surveillance jet named the SR-72.

As the 40th anniversary of their famous flight draws near, Joersz is considering a trip to Georgia to reconnect with the plane that put him in the record books. “I felt very, very fortunate to be a guy that was flying this wonderful airplane,” he said.

The bonds between these machines and their flight crews still run deep. Morgan, now 74, also would love to reunite with the fastest plane in the world. “The first thing you would do is walk up to it and touch it,” he said, and relive a few supersonic memories.

“That’s my baby,” Morgan said. “She did her job and she came through.”