Story highlights

Zully Broussard decided to give a kidney to a stranger

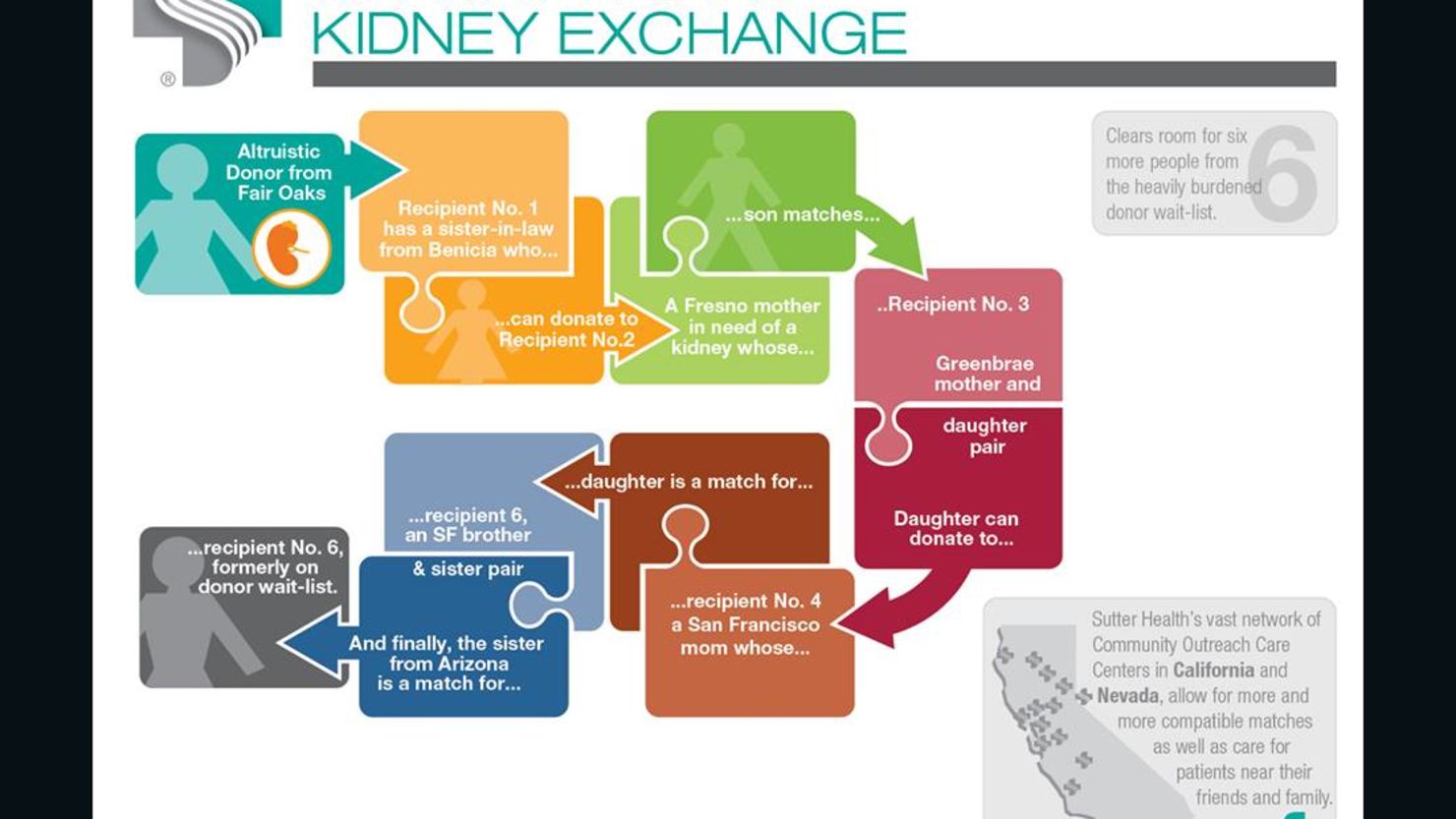

A new computer program helped her donation spur transplants for six kidney patients

Share, and your gift will be multiplied.

That may sound like an esoteric adage, but when Zully Broussard selflessly decided to give one of her kidneys to a stranger, her generosity paired up with big data. It resulted in six patients receiving transplants.

That surprised and wowed her.

“I thought I was going to help this one person who I don’t know, but the fact that so many people can have a life extension, that’s pretty big,” Broussard told CNN affiliate KGO.

Higher powers

She may feel guided in her generosity by a higher power.

“Thanks for all the support and prayers,” a comment on a Facebook page in her name read. “I know this entire journey is much bigger than all of us. I also know I’m just the messenger.”

CNN cannot verify the authenticity of the page.

But the power that multiplied Broussard’s gift was data processing of genetic profiles from donor-recipient pairs. It works on a simple swapping principle but takes it to a much higher level, according to California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco.

So high, that it is taking five surgeons, a covey of physician assistants, nurses and anesthesiologists, and more than 40 support staff to perform surgeries on 12 people. They are extracting six kidneys from donors and implanting them into six recipients.

“The ages of the donors and recipients range from 26 to 70 and include three parent and child pairs, one sibling pair and one brother and sister-in-law pair,” the medical center said in a statement. The chain of surgeries is to be wrapped up Friday.

In late March, the medical center is planning to hold a reception for all 12 patients.

Here’s how the super swap works, according to California Pacific Medical Center.

Kidney square dance

Say, your brother needs a kidney to save his life, or at least get off of dialysis, and you’re willing to give him one of yours.

But then it turns out that your kidney is not a match for him, and it’s certain his body would reject it. Your brother can then get on a years-long waiting list for a kidney coming from an organ donor who died.

Maybe that will work out – or not, and time could run out for him.

Alternatively, you and your brother could look for another recipient-living donor couple like yourselves – say, two more siblings, where the donor’s kidney isn’t suited for his sister, the recipient.

But maybe your kidney is a match for his sister, and his kidney is a match for your brother.

So, you’d do a swap. That’s called a paired donation.

It’s a bit of a surgical square dance, where four people cross over partners temporarily and everybody goes home smiling.

Domino effect

But instead of a square dance, Broussard’s generous move set off a chain reaction, like dominoes falling. Her kidney, which was removed Thursday, went to a recipient, who was paired with a donor.

That donor’s kidney went to the next recipient, who was also paired with a donor, and so on. On Friday, the last donor will give a kidney to someone who has been biding time on one of those deceased donor lists to complete the chain.

Such long-chain transplanting is rare. It’s been done before, California Pacific Medical Center said in a statement, but matching up the people in the chain has been laborious and taken a long time.

Paying it forward

That changed when a computer programmer named David Jacobs received a kidney transplant. He had been waiting on a deceased donor list, when a live donor came along – someone nice enough to give away a kidney to a stranger.

Jacobs paid it forward with his programming skills, creating MatchGrid, a program that genetically matches up donor pairs or chains quickly.

“When we did a five-way swap a few years ago, which was one of the largest, it took about three to four months. We did this in about three weeks,” Jacobs said.

The real miracle

But this chain wouldn’t have worked so quickly without Broussard’s generosity – or may not have worked at all.

“The significance of the altruistic donor is that it opens up possibilities for pairing compatible donors and recipients,” said Dr. Steven Katznelson. “Where there had been only three or four options, with the inclusion of the altruistic donor, we had 140 options to consider for matching donors and recipients.”

And that’s divine, Broussard’s friend Shirley Williams wrote in a comment her on Broussard’s Facebook page.

“You are a true angel my friend.”