Samantha Elauf was apprehensive to interview for a sales job at retailer Abercrombie & Fitch in 2008 because the 17 year old wore a headscarf in accordance with her Muslim faith. But a friend of hers, who worked at the store, said he didn’t think it would be a problem as long as the headscarf wasn’t black because the store doesn’t sell black clothes.

Ultimately Elauf failed to get the job, and her story has triggered a religious freedom debate regarding when an employer can be held liable under civil rights laws. The Supreme Court heard arguments in the case on Wednesday.

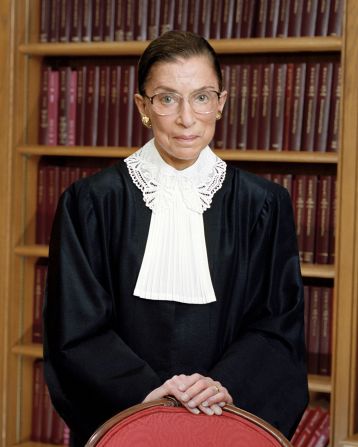

READ: Ginsburg and Scalia on parasailing, elephants and not being ’100% sober’

Like many retailers Abercrombie has a “look policy” aimed to promote what it calls its “classic East Coast collegiate style of clothing.”

When Elauf sat down with assistant manager Heather Cooke to formally interview for the job, neither the headscarf nor religion ever came up. Cooke did refer to the policy, however, telling Elauf that employees shouldn’t wear a lot of make up, black clothing or nail polish.

Cooke thought Elauf was qualified for the job, but after the interview sought approval from her district manager regarding the headscarf. She says she told the manager that she assumed Elauf was Muslim and figured she wore the headscarf for religious reasons. The manager told her that Elauf should not be hired because the scarf was inconsistent with the “look policy.”

A federal agency, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission sued on Elauf’s behalf saying the store had discriminated on the basis of religion in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The law makes it illegal for an employer to “fail or refuse to hire” an individual because of an individual’s religion unless an employer demonstrates that he is unable to reasonably accommodate a religious observance or practice “without undue hardship on the conduct of the employer’s business.”

Abercrombie does not dispute that Elauf was not hired because of her headscarf. The company says its “look policy” is neutral on religion, but that employees are not allowed to wear headgear.

Although Elauf won at the district court level, a federal appeals court ruled in favor of Abercrombie holding that the employer could not be held liable because Elauf never informed the company that she wore the scarf for her religious beliefs and that she need an accommodation because her headscarf conflicted with the store’s clothing policy.

In court briefs, lawyers for Abercromie say that they their audience are “tough customers” in part because the stores must retain their business “through the vicissitudes of teen and young adult fashion.”

“Messages that deviate from a brand’s core identity weaken the brand and reduce its value,” said lawyer Shay Dvoretzky .

The company prohibits facial hair, obvious tattoos and long fingernails. Caps are not allowed to be worn on the sales floor. The store says it has granted religious exemptions that have been requested over the years to employees – some of them Muslim – after evaluating them on a case-by-case basis. In this instance, Elauf never asked for such an exemption.

“At its core, this case presents the question of when an employer must initiate a dialogue with its employee or prospective employee about any possible religious accommodations that may be necessary under Title VII.,” lawyers for the libertarian Cato Institute argued in court briefs in support of Abercrombie.

“The answer is that the employer must have actual notice of a potential conflict between an employee’s religious practices and the employer’s workplace rules and policies – and that the employee bears the burden of providing that notice,” they wrote.

But the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, a nonprofit group with an interest in religious freedom, has filed a friend of the court brief supporting Elauf.

“Abercrombie’s claim is both absurd and a dangerous precedent for all people of faith seeking an exception,” Eric Baxter, a lawyer for the group,

“We want the court to recognize that the notice requirement has to be flexible,” said Baxter. “There can’t be some strict requirement that an employee has to say certain words before the employee’s religion is protected.”

The case will be decided this spring.