Story highlights

NEW: Official: An FBI inquiry is looking into whether federal hate crime laws were violated

Family members and Muslims around the world say it was a hate crime

Police are saying it was a dispute over a parking place

The cries from family members and shocked Muslims are clear: Call it what it is, a hate crime.

They say Craig Stephen Hicks hated religion and that he was riled at the sight of his Muslim neighbors: two of them young women who wore hijabs.

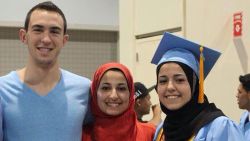

The deaths of Deah Shaddy Barakat, 23; Yusor Mohammad, 21; and Razan Mohammad Abu-Salha, 19, had the hallmark of a summary execution: shots fired to the victims’ heads.

But police in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, said the Tuesday evening shooting appeared to be fueled by rage over a parking space. Hicks’ wife said it was a dispute between neighbors.

The FBI has opened a preliminary inquiry into the killings to look into whether the slayings violated federal hate crime laws or other federal laws, a U.S. law enforcement official said Wednesday. But the official also said so far investigators haven’t found any indications of a hate crime, and evidence suggests the slayings resulted from a confrontation over a parking dispute.

Some allege there’s a double standard at play here. They say that if the situation was reversed, law enforcement and the media wouldn’t hesitate to call it a hate crime or a terrorist act.

When is something a hate crime?

It’s a hate crime when violence is tinted with discrimination.

The FBI defines it as “a traditional offense like murder, arson, or vandalism with an added element of bias.”

That bias can go, among other things, against race, gender, sexual orientation or disability.

“To qualify as a hate crime, all that matters is that the crime was motivated, in whole or in part, by the offender’s bias,” CNN legal analyst Sunny Hostin said.

It also applies in cases of mistaken identity – for example, it someone attacks a person because he thinks they’re gay, but they’re not.

After the 911 attacks, some Sikh men, who typically wear turbans, were mistaken for Muslims and attacked.

Does it make a difference legally?

In the justice system, the old adage that words can never hurt you is dead wrong.

Labeling something a “hate crime” can make the law come down much harder on a defendant. It adds a new serious charge that can come with a heavy additional sentence.

In 2013, a Mississippi judge sentenced Deryl Dedmon – a white man who killed James Craig Anderson, an African-American, in a clearly racist attack – to two concurrent life terms.

He and friends had expressly set out for a night of targeted hassling of black people, screaming racial insults and yelling, “White power.”

Though it’s the states that try hate crimes as a rule, federal authorities can push forward their investigation and prosecution.

Take Dedmon’s example.

He caught the wrath of the federal government as well. On Tuesday, he was sentenced to 50 years in a federal prison.

“The defendants targeted African-American people they perceived as vulnerable for heinous and violent assaults – hate crimes, motivated solely by race, that shook an entire community and claimed the life of an innocent man,” Attorney General Eric Holder said in a statement.

Finally, even if a defendant is acquitted on a state level, the Justice Department can prosecute a case as a “hate crime.”

Case in point: In 2011, a federal court convicted two Pennsylvania men of a hate crime after the state acquitted them of murder.

Derrick Donchak and Brondon Piekarsky had repeatedly kicked a Mexican man in the head while hurling racist slurs at him. The man died.

What about the ‘terrorism’ label?

That, too, has legal ramifications, and is not applied lightly.

The feds have a very specific definition of when something is an act of domestic terrorism.

It has to have three characteristics: an act that takes place in the United States, that’s dangerous to human life, and is intended to intimidate civilians or affect government policy by “mass destruction, assassination or kidnapping.”

Probably the best example is the Fort Hood shooting in 2009. To the victims at the Texas base, it was an act of terror, when Maj. Nidal Hassan opened fire on his fellow service members.

But federal authorities never used the terrorism label. It met some of the criteria, but it was a legal move. Avoiding the label made it easier for them to pursue the death penalty.

Why doesn’t the ‘hate crime’ label seem to apply here?

There’s not much concrete evidence of bias, police in North Carolina say. They’re searching Hicks’ computer and so far have not come up with anything that points in that direction, a law enforcement official briefed on the investigation told CNN.

Hicks’ wife, who is in the midst of divorce proceedings, told journalists she’s convinced religion had nothing to do with it. Her divorce lawyer, Rob Maitland, said the shooting “highlights the importance of access to mental health care services.”

He declined to provide any details about the suspect’s mental health history, but said, “obviously it’s not within the range of normal behavior for someone to shoot three people over parking issues.”

So, why are people calling it a ‘hate crime’?

On what is believed to be his Facebook page, Hicks is quite vocal about his atheism. Those alleging it’s a hate crime are passing around a post attributed to him:

“When it comes to insults, your religion started this, not me. If your religion kept its big mouth shut, so would I.” CNN cannot confirm the authenticity of the post.

By itself, it’s thin, said CNN legal analyst Mark O’Mara.

It’s “one piece of evidence that suggests that he had a hatred or dislike for the Muslim community – potentially. If that was the only piece of evidence, I don’t think it’s enough, quite honestly,” he said.

Contrast this case with the Kansas City shooting last year in which Frazier Glenn Cross is accused of opening fire at two Kansas Jewish centers. The three people he killed were Christian.

Organizations that track hate groups described Cross, who is also known as Frazier Glenn Miller, as a long-time white supremacist. Another indication of his mindset were the words he shouted from the back of the patrol car after his arrest: “Heil Hitler.”

Soon afterward, Overland Park Police Chief John Douglass said investigators had “unquestionably determined … that this was a hate crime.”

What happens next?

Mohammad Abu-Salha, who lost both of his daughters in the slaying, is sure the women’s hijabs had something to do with it.

When his son-in-law lived alone in the condominium complex, the family never had any problems. But once his daughter moved in, wearing a head scarf that clearly identified her as Muslim, trouble started, Abu-Salha said.

“Daddy, I think he hates us for who we are,” Abu-Salha said his daughter Yusor Mohammad told him.

It has been two days since the attacks, and the investigation is far from complete.

As details about the case are still emerging, a lot of questions persist. The FBI is assisting police. And Chapel Hill authorities aren’t ruling out any options.

“We understand the concerns about the possibility that this was hate-motivated, and we will exhaust every lead to determine if that is the case,” Chapel Hill Police Chief Chris Blue said.

But in the end, does a motive really matter?

Barry Saunders, writing in the News and Observer, put it best.

“If the deaths resulted from a hate crime, it is an international tragedy.

“If the deaths came simply because a man was consumed with a general hate for all humanity – heck, then it’s still an international tragedy. Because people all over the world have now been deprived of the services Deah, Yusor and Razan would have rendered unto them.”

Opinion: 3 slain college students strived for a better world

CNN’s Evan Perez and Jason Carroll contributed to this report.