Editor’s Note: Julian Zelizer is a professor of history and public affairs at Princeton University and a New America fellow. He is the author of the new book, “The Fierce Urgency of Now: Lyndon Johnson, Congress and the Battle for the Great Society.” The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

New film 'Selma' tells story of violent repression of civil rights protests, leading to enactment of Voting Rights Act

Julian Zelizer says the film gets most of the story right but misrepresents LBJ's role

Sometimes ordinary people can have an extraordinary impact on American politics. The new movie “Selma” recreates the grass-roots protests that resulted in the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In this riveting film, audiences get to see how average citizens have been able to push politicians to take action that they don’t have the courage to do on their own.

The movie depicts President Lyndon Johnson as a leader who was extraordinarily hesitant, to the point of being hostile, toward proposing a voting rights bill.

“The voting thing is going to have to wait,” Johnson tells a frustrated Martin Luther King Jr. in one scene. “It can’t wait,” King responds. The storyline of the movie revolves around a courageous group of civil rights activists who put their lives on the line when Washington wasn’t helping them until they convinced the President to send a bill to Congress.

After the violent response by police to the marchers, Johnson finally listens to King, who had warned that he will be remembered as “saying ‘wait’ and ‘I can’t.’ “

A controversy has opened up about the film, with a number of critics, including former members of the administration, pointing out that the movie offers a skewed portrayal of LBJ. He comes across as a president uninterested in voting rights and primarily focused on secret FBI surveillance of King.

The best place to look for some answers is in the historical archives. This is the first in a series of columns this month that I will be writing that explore some of the conversations in the White House telephone recordings of President Johnson—on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Great Society, the wide range of domestic programs enacted by the 89th Congress in 1965 and 1966—to understand some of the lessons that these conversations offer us in today’s political world.

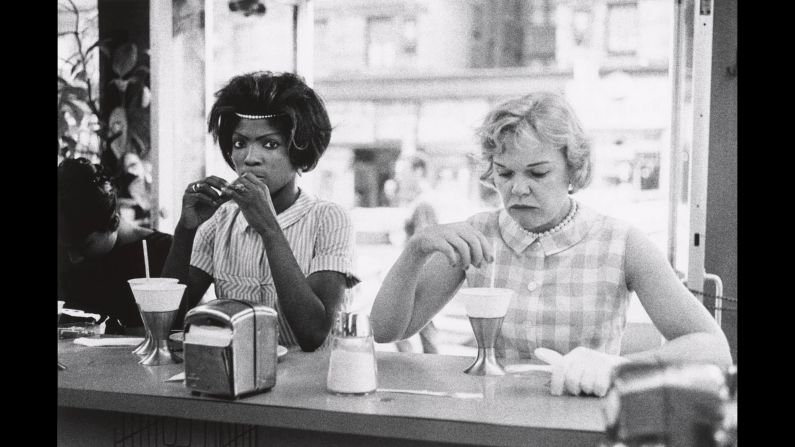

By the time of his landslide election victory against Arizona Republican Barry Goldwater in 1964, President Johnson believed that Congress needed to pass a strong voting rights bill that would guarantee the ability of African-Americans to register to vote and actually cast their choice on election day. For much of his life he had been opposed to the racial inequality of the South and the civil rights movement in the 1950s and early 1960s had further strengthened his belief in the necessity of federal legislation. In 1964, Congress, with Johnson’s strong support, had passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which ended racial segregation in public accommodations.

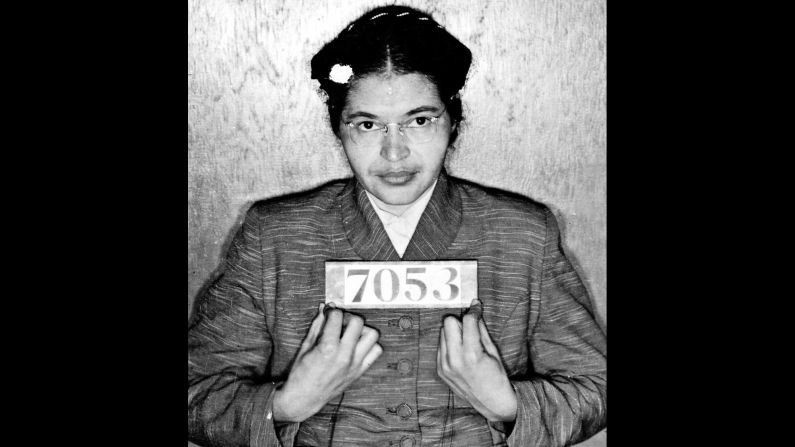

President Johnson didn’t need any more grass-roots protests to convince him that voting rights legislation was necessary. This is one big thing the movie gets wrong, which has led some scholars, including the head of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library and Museum and former adviser Joseph Califano to rightly complain of how the film depicts him. Indeed, the White House tapes tell a very different story. Only a month after his election victory, President Johnson can be heard telling Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach on December 14, 1964, that he should start crafting a strong piece of legislation that would create a “simple, effective” method to register African-Americans to vote.

Over the next few months, Johnson instructed Katzenbach to conduct secret negotiations with Republican Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen to design the framework for a bill, which they would reach agreement on by early March.

But the movie is correct in asserting that Johnson disagreed with civil rights leaders on the timing; he was not ready to actually propose a bill to Congress. While Johnson wanted a bill, he didn’t feel he could deal with the issue until later in 1965. Johnson feared that the time was not right. He sensed that he wouldn’t be able to find enough support in the House and Senate.

Congress had just passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, he said, so another heated debate over race relations could tear the Democratic Party (then divided between Southern Democrats and liberal northerners) apart.

Civil rights activists were unwilling to wait any longer. They believed that when Congress refused to act on major civil rights issues, always with the justification that the time was not yet right, the chances increased that the bill would never see the light of day.

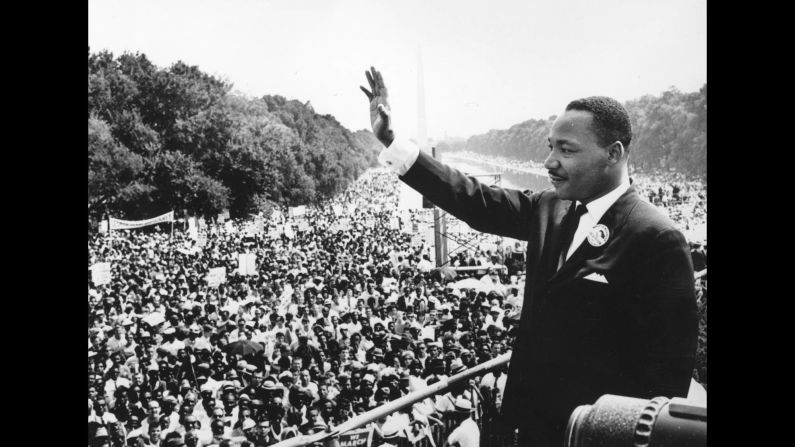

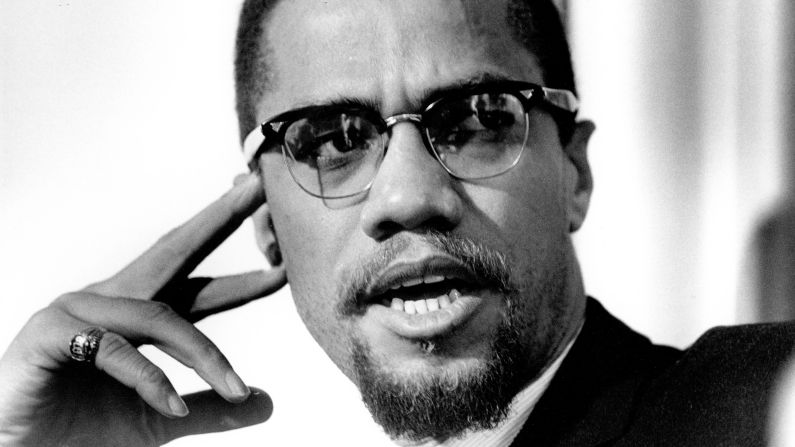

King liked to speak about the “fierce urgency of now,” by which he meant that it was intolerable to postpone resolving the fundamental issues of the day. In American politics, delay was often the way major legislation was left to die.

Johnson, who for years had seen the kind of trickery Southern conservatives were capable of when it came to civil rights, could not be moved by logic. During a conversation with King on January 15, 1965, the President made it clear to the civil rights leader that he was determined on moving forward on a number of other domestic issues, such as education, Medicare, poverty and more (all of which, Johnson reminded him, would be enormously helpful to African Americans).

In Johnson’s view, they had to get the bills passed before what he called the “vicious forces” concentrated in Congress to block them. King tried to appeal to Johnson’s practical side, highlighting how the African-American vote in the South would create a powerful coalition, along with moderate whites, in a “New South.” Johnson would have none of this.

Johnson says to King that he and the civil rights movement needed to help him build support for legislation by talking about the kind of rights violations that were common in the South. But he was not prepared to send anything to Congress. The proposal would have to wait.

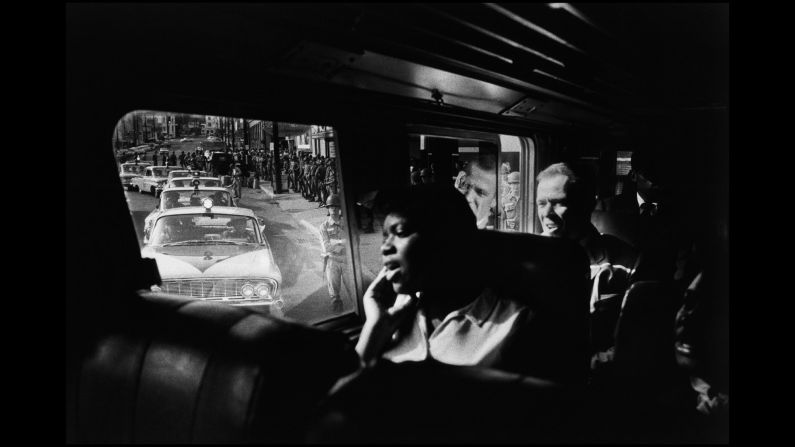

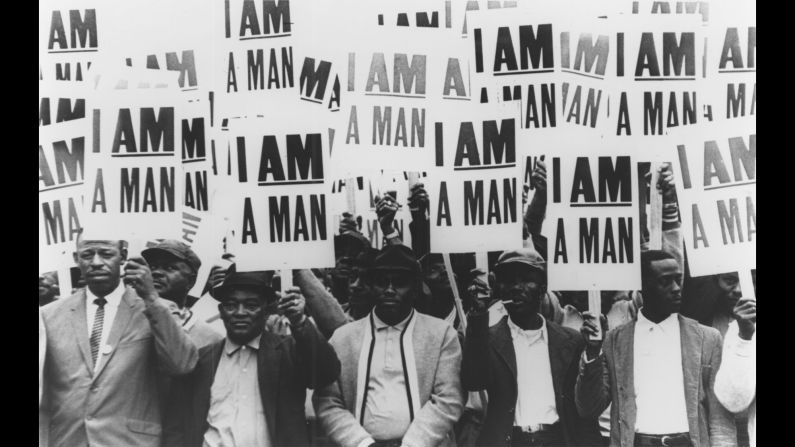

This is the moment when the civil rights activists stepped in. King had warned Johnson that if Congress did not take up this issue, activists would force them to do so. The civil rights movement mobilized in Selma, Alabama, one of the most notoriously racist cities in the South, to organize protests in favor of voting rights.

The violence the activists encountered when they were viciously attacked by Sheriff James Clark, an ardent racist who dressed in military garb and wore a button that said “Never!” and his men was shocking. As Johnson watched and read the news, he became convinced he might have to take action sooner than he thought.

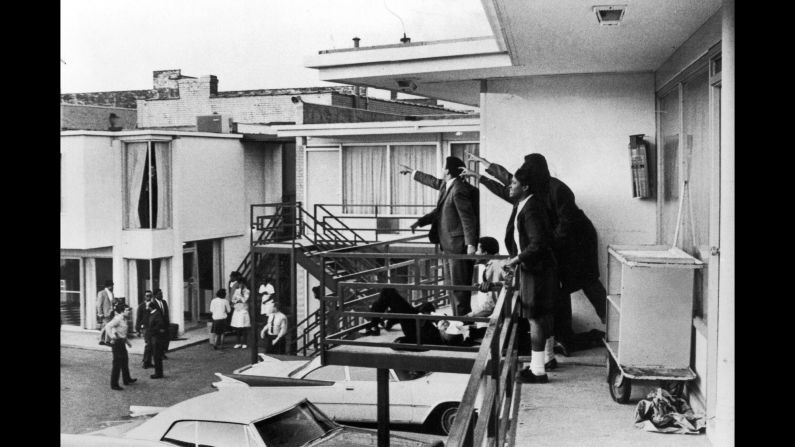

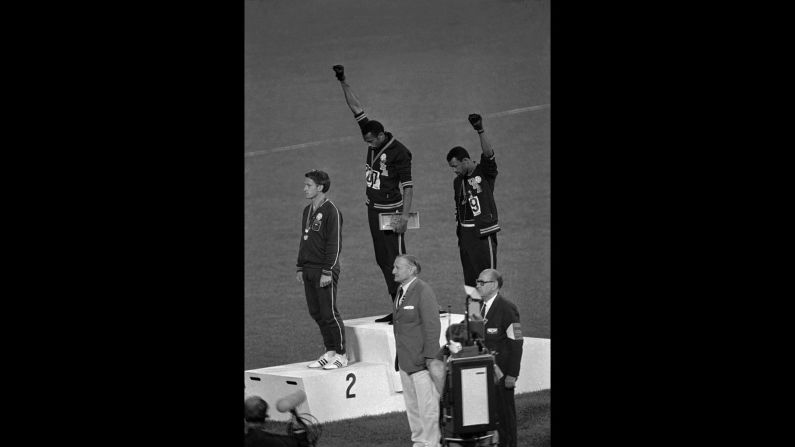

The protests culminated with the historic march from Selma to Montgomery over the Edmund Pettus Bridge on March 7. The violence that protesters encountered over the Pettus Bridge, on a day that would be remembered as “Bloody Sunday,” shocked legislators and the President into concluding that legislation was needed immediately. As Rep. John Lewis, then Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee leader, whose skull was cracked by the police, recalled, “They came toward us, beating us with nightsticks, bullwhips, tramping us with horses, releasing the tear gas. I was hit in the head by a state trooper with a nightstick. My legs went from under me. I thought I was going to die. I thought I saw death.”

On March 10, after asking if the white preacher James Reeb, who had been attacked by white racists after having participated in another march in favor of voting rights, was dead, Johnson admitted to Katzenbach that he was “anxious” the public would see him as a “Southern president” who was tacitly supporting racist law officers allied with the forces against the civil rights movement.

Johnson took action. He delivered a dramatic address to a joint session of Congress that brought Martin Luther King Jr. to tears. The activists had achieved their goal.

Their marches, and the violent response by the white police, had pressured Johnson into taking up this issue before Congress had finished its work on all the other proposals.

In the days that followed the protests, Johnson worked hard to move the bill and to contain the forces of white racism. Johnson called Alabama Gov. George Wallace, who was allowing this violence to take place and doing little to establish order, a “treacherous son of a bitch” when speaking to former Tennessee Gov. Buford Ellington on March 18.

On March 24, 1965, Katzenbach (who had been appointed attorney general in February) felt confident that the civil rights forces were pleased with the administration and the activists were subsiding, though he warned the President that he didn’t want to give the impression “because we get this voting bill quickly … we can all turn our attention to something else and forget about civil rights. Because they’ll continue to raise some hell.” Katzenbach and Johnson were clearly aware of the impact that the grass-roots would have.

The Senate passed the bill on May 26 and the House passed it on July 19, 1965. LBJ signed the bill on August 6.

In the current era, when Congress seems so broken, Selma is an important way to remember that, ultimately, real political change is in the hands of citizens. Leaders, even those who can be bold and who actually want to get things done usually tend to hesitate on tackling controversial issues, often paralyzed by the pressures of political necessity and opposition.

Without citizen pressure, the status quo usually wins even when there is a president who supports reform. But the status quo didn’t win in Selma. Civil rights activists made sure their leaders took action. They gave LBJ the political space he needed to maneuver. The result of their efforts transformed American history. Within only a few months, almost 250,000 new African-American voters were registered to vote with the help of federal protection – and millions more would follow.

Read CNNOpinion’s new Flipboard magazine