Story highlights

Nationwide protests bring back memories of civil rights era to some observers

Protesters motivated by more than anger over Ferguson, experts say

Controversial case for many is latest reminder of justice system failures

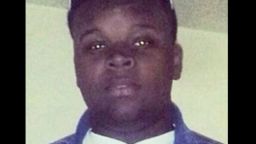

The rage echoing across the nation after a grand jury’s conclusion in Ferguson, Missouri, goes far beyond the decision not to indict white police Officer Darren Wilson in the death of unarmed black teen Michael Brown.

Protesters have blocked bridges and tunnels, spilled into roadways and disrupted Black Friday shopping in more than 150 cities in mostly peaceful protests that conjure memories of the civil rights movement for some. The demonstrators were furious at the grand jury decision, but their frustration transcends anger over what happened between Wilson and Brown in the shadow of St. Louis one Saturday afternoon in August.

“It’s bigger than what happened in Ferguson,” said Dorothy Brown, a law professor at Emory University School of Law in Atlanta.

After the grand jury completed its work, many around the United States have interpreted what happened in Ferguson squarely in the context of a larger, historic narrative about race and justice in America.

To them, Ferguson is just the latest reminder that the American criminal justice system doesn’t treat blacks and whites the same – and that young black men in particular are often killed with impunity.

“It’s sort of a quasi-movement that’s afoot,” said Matthew Whitaker, a history professor who directs the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at Arizona State University. “And what we can attribute this to is the fact these things seem to happen so regularly now that the frustrations folks are feeling are leading them to plan almost in advance.”

A week ago inCleveland, a white police officer shot and killed a 12-year-old black boy, Tamir Rice, seconds after a squad car pulled up. The officers were investigating reports of someone pointing a gun at people. Police said Tamir had an air gun that looked real.

Some protesters in Cleveland linked Tamir’s death with Brown’s. One held a sign that said “Michael Brown to Tamir Rice, this must stop.” Others had signs that said things such as “the whole damn system is guilty!”

Last year, marchers took to the streets in several cities after a jury in central Florida acquitted George Zimmerman, who identified himself as Hispanic, in the shooting death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, who was black. Zimmerman said he killed Martin in self-defense after the teenager attacked him.

The visible reaction to Brown’s death was even more widespread.

“Ferguson’s hell is America’s hell,” hundreds of students chanted this week at historically black Morehouse College in Atlanta, where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. earned his first degree.

Echoes of the past

The case in Ferguson has reminded some people of unsavory episodes from America’s past.

Wilson described Brown to grand jurors and a national television audience, for example, in a way that offended some, buttressing their view of how too many white police officers see and treat black men.

Wilson told the grand jury that Brown looked “like a demon.” In an interview with ABC News, he described Brown as almost super-human.

“I just felt the immense power that he had,” said Wilson, who is about 6-foot-4 and 210 pounds. “It was like a 5-year-old holding onto Hulk Hogan. That’s just how big this man was.”

Brown was about the same height as Wilson. He weighed nearly 300 pounds.

Whitaker, the history professor, heard echoes of the past in the way Wilson described Brown.

“That’s always been one of the painful realities on the black community, is the perception of black men,” Whitaker said. “We’re regularly portrayed as being these gigantic, threatening, dangerous, oversexed individuals.”

He added, “At the end of the day, Michael Brown was essentially a kid, and if you can’t see the humanity in a kid, even a recalcitrant kid, there’s something wrong with that.”

Another aspect of the case that caused some to draw historic parallels: The fact that authorities left Brown’s body on the street for four hours.

“The nicest thing you can say is that it’s the most insensitive thing we’ve seen in a long time,” said Dorothy Brown, the law professor. “The other extreme is, this was done deliberately. It’s sending a signal. We don’t want anybody challenging the status quo. Here is a body as a reminder.”

Some people compared the immediate aftermath of Brown’s death to a lynching in the old South. They drew parallels to a time of public hangings, when mobs killed blacks, sometimes for perceived infractions such as stealing, and left the bodies in public to sow fear.

Police said officials couldn’t reach the area where the body lay because a crowd had gathered, making it too dangerous. Ferguson’s police chief, Thomas Jackson, later apologized to Brown’s family.

“I’m truly sorry for the loss of your son. I’m also sorry that it took so long to remove Michael from the street,” he said in a videotaped statement.

Whitaker sees links between Michael Brown and historical figures such as Emmett Till, a 14-year-old black boy murdered in Mississippi in 1955 for allegedly violating an unwritten Southern racial code by whistling at a white woman.

Assailants abducted him at night from his great-uncle’s home and tortured and murdered him. Their actions drew national attention to a prejudiced and corrupt legal system in the Jim Crow South.

“Certainly there are connections,” Whitaker said. “All you have to do is say, ‘Emmett Till,’ and images and a time period and feelings come to mind. It’s the same with Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown.”

Jason Johnson, a professor of political science at Hiram College in Ohio and CNN contributor, grew up 30 minutes south of Ferguson and spent time there studying the government response to Brown’s killing.

“I have been saying sort of tongue in cheek and very seriously, institutional racism actually works better than this,” Johnson said. “This is incompetence.”

Dorothy Brown drew a similar conclusion.

“They’re not used to being held accountable,” Brown said of Ferguson officials. “This is what absolute power looks like. That’s why it reminds me of the South in the ’50s and ‘60s.”

The nationwide interest in the case also had people making historical comparisons.

Before the grand jury decision, U.S. Rep. John Lewis predicted that a “miscarriage of justice” in the case would create the “same feeling and climate and environment that we had in Selma.” Lewis is a black Democrat from Georgia who was among demonstrators police beat in a civil rights march in Selma, Alabama, in 1965.

“Selma was the turning point,” Lewis told Roland Martin’s radio program “News One Now.” “And I think what happened in Ferguson will be the turning point.”

A powerful reaction across the country

Events in Ferguson triggered a national response, experts said, because they embodied themes that resonated far beyond Missouri – and because social media let people follow along and share opinions in real time.

Last year, a Pew Research Center survey showed that seven of 10 African-Americans, and nearly four in 10 whites, felt blacks were treated less fairly than whites in dealings with the police.

Nearly a quarter of black men ages 18 to 34 reported that police treated them unfairly in the past 30 days, according to a 2013 Gallup poll.

“I would argue the protests that are occurring in Atlanta, in San Francisco, in New York, in Chicago and Cleveland are actually more powerful than the ones in Ferguson,” Johnson said.

In an editorial, The New York Times said this week that “many police officers see black men as expendable figures on the urban landscape, not quite human beings.” The distrust “presents a grave danger to the civic fabric of the United States,” the editorial said.

A report by ProPublica found that young black men were 21 times as likely as their white counterparts to be shot to death by police, the newspaper said.

“Those are the types of statistics that have been with us for a while, but people are finally starting to understand their gravity,” Whitaker said.

It was against that backdrop that people shared news on social media of what transpired in Ferguson, helping transform a local news story into a national conversation.

From August 9, the day that Wilson killed Brown, to August 25, the #Ferguson hashtag was used on Twitter 11.6 million times with retweets and 1.9 million without retweets, according to Sysomos.

After Monday night’s grand jury announcement, the news spread on social media, with Twitter mapping the explosive use of the #Ferguson hashtag.

Post-racial America?

The unrest that greeted the grand jury decision laid bare to many that a post-racial America remains elusive despite the election and re-election of Barack Obama, America’s first black president, and the service of its first black attorney general, Eric Holder.

“We thought we had symbolically and, in some substantive ways, come to a place we’ve never been,” Whitaker said. “How painfully ironic is it that you have these types of representations at the highest levels, yet we still see the smoldering tensions of racial and economic discord bubbling over.

“At the same time, African-American lives, young people, poor people seem to be worth less than the dominant population.”

Holder has opened two civil rights investigations in Missouri – one into whether Wilson violated Brown’s civil rights, the other into the police department’s overall track record with minorities.

The December 8 cover of The New Yorker magazine illustrates the tragic rift in Ferguson as well as other U.S. cities. The magazine cover shows the Gateway Arch in St. Louis broken and divided by color – one part white, one black.

African-American activist Myrlie Evers-Williams, widow of slain civil rights activist Medgar Evers, told CNN on Friday that it is tragic that America still dealing with hatred against blacks.

Asked if Obama should visit Ferguson, she said: “I don’t know if he should go, but he should speak loudly, strongly his beliefs, and to all of the American public, that it is not just a black problem, it’s a problem of all Americans. How dare we tell the rest of the world how to live when we don’t carry out that message within ourselves?”

Yet Johnson said he found reason for hope.

“For the first time in American history, you have a reasonable number of white Americans who actually think this is a problem,” he said.

Adding complexity to the national picture is the arrival in recent years of hundreds of thousands of immigrants, including many from countries with corrupt police forces.

“They’re bringing with them heightened concern and distrust” of the police, Whitaker said. “And younger people are identifying with it, and those younger people could be poor white Americans. It’s spreading.”

And people around the United States already are preparing responses to the next Ferguson, Whitaker said.

“Folks are anticipating … these types of tragic incidents,” he said. “Each time, it’s going to become large and more intense.”