Story highlights

Nigeria's claim of a truce with Boko Haram raised hopes for release of kidnapped girls

But Boko Haram's leader Abubakar Shekau issued a video denying any ceasefire

Shekau said he did not know the negotiator claiming to represent Boko Haram

The girls kidnapped from Chibok, he said, had converted to Islam and been married off

Abducted. Sold. On the brink of freedom. Converted to Islam and married off … despite the claims and counterclaims the fate of more than 200 girls kidnapped by Boko Haram on April 14 remains as unclear as ever.

On October 17, Nigerian officials announced they had reached a ceasefire deal with Boko Haram that included the girls’ release.

Hassan Tukur, principal secretary to President Goodluck Jonathan said the deal followed a month of negotiations with representatives of the group in Chad.

“We have agreed on the release of the Chibok schoolgirls, and we expect to conclude on that at our next meeting with the group’s representative next week in Chad,” he said.

The announcement revived hopes the girls’ would be released and reawakened the #BringBackOurGirls hashtag on Twitter.

But analysts questioned the veracity of the government’s claim and Boko Haram remained silent on the ceasefire – and active in northeastern Nigeria, where it carried out more attacks and abductions.

Finally, on November 1, a video appeared of the group’s leader, Abubakar Shekau saying no ceasefire been reached.

As for the girls, Shekau said they had converted to Islam and had been married off, saying with a chuckle in the video: “They are in their marital homes.”

So did Nigeria’s government truly believe it had reached a truce with Boko Haram?

CNN’s Isha Sesay has covered the girls’ abduction since they were taken from Chibok and traveled to Nigeria after last month’s announcement they were to be released. Sesay says indications are that talks certainly had been taking place.

“From people I’ve spoken to on the ground, it does seem that there was some effort under way to free the girls,” she said.

But Sesay says some sources believe the Nigerian government may have been dealing with the wrong people.

In an article for CNN last week, analyst Darren Kew also pointed out that many Nigerian journalists had questioned whether the man said to be negotiating on behalf of Boko Haram’s leadership was a genuine representative of the group.

In his video, Shekau certainly indicated that he was not, denying knowing the man and adding: “We will not spare him and will slaughter him if we get him.”

After the Boko Haram leader’s message, Nigeria’s government again reiterated that negotiations had taken place, saying Shekau’s comments contradicted assertions made in conversations with Nigerian officials.

“We’ve heard about the video, and we can say the road to peace is bumpy – and you cannot expect otherwise,” a spokesman said. “Nigeria has been fighting a war, and wars don’t end overnight.”

What clues are there as to the girls’ whereabouts?

This is the crucial unanswered question.

CNN’s Nima Elbagir visited Chibok in May and met with a girl who had managed to flee from Boko Haram the night of the abduction.

The girl told Elbagir how she made a dash for freedom after militants loaded them into trucks and drove them into the nearby Sambisa Forest. President Jonathan also said the girls were in the forest, which at that time was an Boko Haram stronghold.

Sesay says that belief had persisted for a long time but the militants – and therefore the girls – were no longer thought to be in that area.

“The feeling among Nigerian government officials I have spoken to is that the girls were broken into groups and have been dispersed along the Chad, Cameroon and Niger borders – that they’re in those border areas,” she said.

What about Shekau’s claim the girls have been married off?

On October 27, Human Rights Watch (HRW) released a report on Boko Haram violence against women and girls in Nigeria after interviewing kidnap victims including 12 of the Chibok girls.

“The victims were held in eight different Boko Haram camps that they believed to be in the 518-square-kilometer Sambisa Forest Reserve and around the Gwoza hills for periods ranging from two days to three months,” the report said.

“The women and girls told Human Rights Watch that for refusing to convert to Islam, they and many others they saw in the camps were subjected to physical and psychological abuse; forced labor; forced participation in military operations, including carrying ammunition or luring men into ambush; forced marriage to their captors; and sexual abuse, including rape.”

HRW documented eight cases of sexual violence by Boko Haram combatants saying “most cases of rape occurred after the victims were forced to marry.”

Sesay said the report suggest that the girls have likely been married off to Boko Haram combatants, who are believed to number around 10,000.

“If indeed Shekau’s statements are true, it’s probably likely that they have been married to Boko Haram fighters or to Boko Haram supporters,” she said.

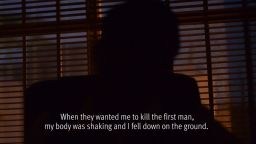

Who would fight for Boko Haram?

Human Rights Watch said witnesses had described the abduction of men and boys – especially those of fighting age – by Boko Haram.

“The men and boys are often given the option of joining the group or being killed. Other men appeared to have been targeted for abduction because of their specific skills or occupation, which filled a need in the insurgents’ camp,” the group said in its October report.

But not all combatants are forced.

“One thing that I keep hearing when I’m in Nigeria is the question of ‘Who is Boko Haram?’ says Isha Sesay. “Is it ideologues? Is it young people from those very communities who are almost like mercenaries who become involved because they are going to be paid and make some money?

“According to some security experts I spoke to they’re not all Nigerians, some of them are from those neighboring countries and some of them are paid fighters.”

Where does support for the group come from?

The notion of support for Boko Haram is complicated, says Sesay.

“When Boko Haram first sprang up, they rose with an agenda of trying to address the inequality between the Muslim north – which has been under invested in and has high levels of poverty and lower levels of education – and the rest of the country. It was about social ills – that’s what they originally came onto the scene professing.”

But in 2009, the struggle became violent. Police killed Boko Haram’s founder Mohammed Yusuf, and he was replaced by current leader Abubakar Shekau.

“When they were a ‘social ills campaign,’ so to speak, they had some amount of support among ordinary Nigerians who felt that here were people who were speaking out on their behalf, saying they needed more support from the government and they’d been long ignored,” Sesay said.

“Things took a turn when they became a violent extremist group that began smashing and burning and murdering people. And I think in the north east – particularly in those three states that are under a state of emergency – it’s just fear – it’s just absolute fear.

“People have fled their homes, there are large camps for internally displaced persons camps scattered around the country with thousands of people in them.

“The instability that this has brought to the north in terms of its economy and its day-to-day life can’t even be quantified. So I think by and large in the north, I don’t hear of civilian support for Boko Haram.”

Read: Boko Haram – the essence of terror

Read: What gives Boko Haram its strength?