Story highlights

- Ara Merjian: Victorian art was not adequate to express WWI's chaos; Modernism stepped in

- He says Picasso's Cubism was suited to times; Futurism and Dada would spring from war

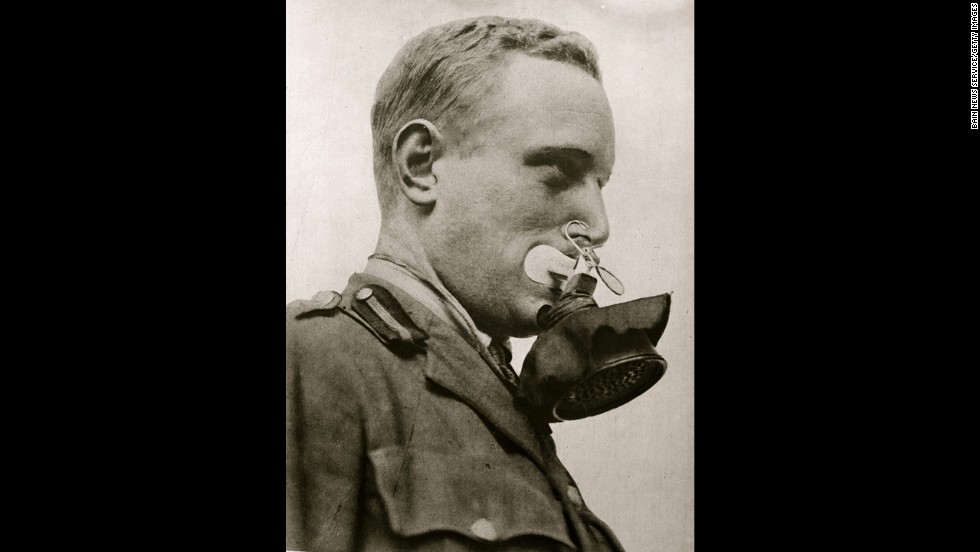

- Apocalyptic imagery emerged, of prostheses, gas masks, corpses, military mechanization

- Merjian: At war's end, soothing images, Surrealism ascended -- a tonic until the next war

The years preceding World War I in Europe are generally referred to as the "Belle Epoque" -- a cultural and economic golden age. The period was hardly one of utter utopia for all citizens. But in the wake of the conflagration that would shake the globe beginning in August 1914, it came later to be seen as a period of calm before the storm. Its cultural practices, too, seem tinged with an almost naive optimism.

Modernism in art and literature had gathered momentum well before the First World War, which began in earnest 100 years ago this fall.

But with its eruption, those earlier Victorian forms no longer seemed adequate in the face of the period's upheavals, the destruction to bodies, to landscape, to culture itself. New experiments took up the task.

The violent disjunctures of Cubist collage, for example, were a fitting way to of express the political and geographic revolution.

Picasso already practiced the form during the Balkan Wars of 1912-13, often using the very newsprint that announced the latest battles. On the Great War itself, the pacifist Picasso remained silent. His innovations with different media and materials, however, influenced movements -- from war-mongering Futurism in Italy to pacifist Dada in neutral Switzerland.

While many artists claimed Cubism itself as a renewed form of classicism, French nationalists derided it as a decadent German import (and spelled it "Kubism" accordingly).

In France as elsewhere, then, culture formed a parallel theater of war. As many artists became enemy combatants with the stroke of a pen, the cosmopolitan idyll of prewar Paris gave way to an increasing xenophobia.

The war and its representations indeed seemed bound up with one another at every turn. "I very well remember," wrote Gertrude Stein, "at the beginning of the war, being with Picasso on the Boulevard Raspail when the first camouflaged truck passed. ... Picasso, amazed, looked at it, and then cried out, yes, it is we who made it, that is Cubism."

The British Vorticist artist Edward Wadsworth not only painted canvases in the sharp lines characteristic of his circle's aggressive imagery, but also supervised the "dazzle" camouflage (an angular patterning of black and white paint) of over 2,000 ships for the British Admiralty.

The seemingly gratuitous bewilderment of modernist abstraction was thus put in the more practical service of confusing rangefinders and eluding enemy fire.

But it was the Italian Futurists who most enthusiastically embraced the war, using their works to agitate for intervention against Italy's traditional ally, Austria. The Futurist ringleader, F.T. Marinetti, declared that only a giant international conflict could shock Italy out of its cultural slumber. Marinetti's hymns to danger, speed and mechanized violence found their consummate realization in the Great War -- an event he deemed "the world's greatest poem."

As volunteers along Italy's northern front, the Futurists served as avant-gardists in the literal, military sense.

Along with their rhetoric of jingoistic virility, Futurist painting and poetry nurtured a playful and subversive "anti-aesthetic" that would inspire artists for the rest of the 20th century. Ironically enough, it was the anti-war stirrings of Dada that bore out its most immediate influence, first in Switzerland and then post-war Berlin.

From Futurism, Dada borrowed strategies of shock and illogic, assaulting received truths and bourgeois morality alike. To these, however, the Dadaists married a resolute anti-nationalism, rejecting both the war and its institutional origins. Yet even politically progressive artists turned to the war's new spectacles as sources of stimulation and dynamism.

Painted while he convalesced from a mustard gas attack, Fernand L├®ger's "The Card Party" (1917) depicts the artist and his fellow French soldiers as virtual extensions of military machinery, their jointed arms mobile like metallic prostheses.

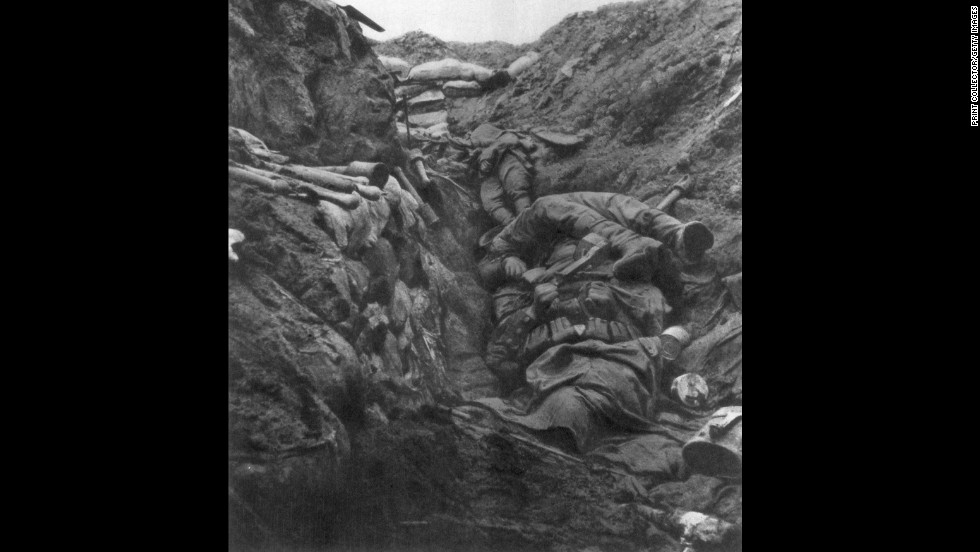

Many drew their inspiration from a newly transformed theater of hostilities, whether the shock of trench warfare, mobile X-ray machines or the terror and poetics of flight (the first pilotless drones were notably developed by the U.S. Navy from 1916-17).

The British sculptor Jacob Epstein's notorious "Rock Drill" (1913-15) features an armored, machine-like body mounted atop an actual rock drill, glorifying an inhuman mechanization and anticipating even the battle droids from the Star Wars franchise's prequel, "The Phantom Menace," at the century's end

Not all European artists figured the period's anxieties -- or witnessed its havoc -- in the same manner.

Following in the tradition of Goya and the Dutch Renaissance alike, Otto Dix would later complete grotesque renderings of soldiers wearing gas masks and battlefields strewn with trenches and corpses. In works made just after the war, he (like his German compatriot George Grosz and other Dadaist artists) incorporated collage into his canvases, evoking the scores of amputated veterans visible in Germany's city streets, themselves virtual assemblages of prostheses.

These artists drew not only upon Futurist experiments with newsprint, but also the Metaphysical cityscapes of the Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico, which conjure up a sense of both post-apocalyptic stillness and disquieting anticipation.

A girl rolls her hoop across a sundrenched square in de Chirico's "Melancholy and Mystery of a Street" (1914), unaware of the hearse that looms in the arcade's shadow -- the metaphor, perhaps, of a continent hurtling toward the void.

The war's traumas also spurred utopian cultural projects after the guns fell silent. During the war, Andr├® Breton worked in a neurological ward in Nantes. His contact with the stream-of-consciousness ramblings of soldiers suffering from head wounds sparked his interest in the unconscious as a source of radical social and political transformation.

Breton's Surrealist movement transformed Dadaist despair -- at both the war and the technologies that had led to it -- into a constructive assault on social and sexual norms. Holding seminars and publishing questionnaires, the Surrealists campaigned in the 1920s and 1930s against the nationalist enmity that had caused the last war and that was leading inexorably toward another.

At war's end, modernist tendencies such as Cubism, Futurism and Expressionism came -- rightly or not -- to be associated with its violence.

But artists generally abandoned the depiction of armored trains and disintegrating forms after the guns fell silent, rendering less threatening subjects in more soothing styles.

Dubbed the "Return to Order" by Jean Cocteau-- the Surrealist painter, poet, playwright, novelist and filmmaker -- this period following the Great War witnessed a reprisal of neoclassical motifs, suckling mothers and other emblems of reassuring stability.

With the gradual rise of fascism, such stability proved itself increasingly illusory, as even the most decorous of aesthetic traditions were put in the service of an aggressive, murderous ideology, and another war -- even more terrible than the first -- tore open the century.