Story highlights

Images and videos of James Foley's beheading are on the Internet

Many media outlets, including CNN, are not showing the video

Internet users and operators must decide how to deal with the video

When confronted by gruesome images of a man being beheaded by terrorists, what should you do?

News organizations have grappled with these kinds of questions for decades. Now, with the prevalence of social media, website operators and ordinary Internet users face the same question.

On Tuesday, when ISIS published a video showing the murder of American journalist James Foley, most Western news outlets shunned the goriest portion of the video but chose to show still photos from the minutes before the beheading.

Some commenters urged news outlets to exercise even more restraint and refrain from using the photos at all.

That same dynamic played out on Twitter and Facebook, as well. As some users shared photos and links to the video, others exhorted them to share earlier photos of Foley’s life and links to examples of his reporting instead. It was almost as if users were collectively developing their own sets of standards.

Kelly Foley, a cousin of the slain journalist, wrote on Twitter, “Don’t watch the video. Don’t share it. That’s not how life should be.”

But there’s a big difference between individual user decisions and institutional decisions by Twitter and YouTube. For the Web sites, blocking objectionable content is a form of editing.

YouTube removes video

The slickly-produced, high-definition video was originally uploaded to YouTube, but was taken off the site within a matter of hours. YouTube also sought to take down duplicates whenever they were posted.

A YouTube representative said the site, owned by Google, has “clear policies that prohibit content like gratuitous violence, hate speech and incitement to commit violent acts, and we remove videos violating these policies when flagged by our users.”

“We also terminate any account registered by a member of a designated Foreign Terrorist Organization and used in an official capacity to further its interests,” the representative added.

Videos of ISIS executions are still accessible through other sites, however. One such site, LiveLeak, said Wednesday that it was “currently experiencing an abnormally high volume of traffic.”

Twitter suspends accounts

Twitter faced similar issues – and a tremendous amount of pressure from its users about the balancing act between freedom of expression and basic human decency.

“We have been and are actively suspending accounts as we discover them related to this graphic imagery,” Twitter chief executive Dick Costolo wrote in an early Wednesday morning post on the site.

It all amounted to a particularly grotesque version of whack-a-mole. At one point Tuesday evening, simply tweeting the word “beheading” resulted in replies from spam accounts that attached a photo of Foley’s severed head.

Twitter briefly suspended the account of a journalist who shared photos of the beheading, but reinstated it later.

Propaganda value of images

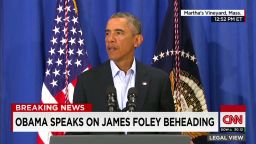

CNN is not airing the video on television or online, but is showing stills from the minutes before the beheading and an audio clip from it.

“It’s news that the executioner’s accent may offer a hint about his identity,” CNN International anchor Jonathan Mann said in a television segment that explained the network’s decision-making.

“It’s news that may change what governments and armies do next. It’s news that other journalists will spread… and that social media will spread without any journalists involved, no matter what we do. It’s news that extremists wanted us all to spread… and they killed a man, at least in part, so that we’d do it.”

Mann added, “What should we do? We thought about it, and we hope we made the right choice.”

The tabloid New York Post newspaper decided to go further, publishing on its front page a frame from the video that shows a terrorist beginning to cut into Foley’s head. The newspaper headline says “SAVAGES.”

Some Internet users subsequently suggested that the Post’s Twitter account should be suspended, too.

The horrific case revived long-running debates about whether news coverage of a terrorist act gives the terrorists the publicity they seek. Many Internet users’ arguments against showing even still images from the Foley video cited the propaganda value of the video.

One of the counter arguments is that people should see – must see – the atrocities.

Some of the same debates took place in 2002, after al Qaeda extremists beheaded the Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl and published the video on the Internet.

Steve Goldstein, who was the head of corporate communications for the Journal at the time, said he had to “urge the networks not to run the video.”

In Foley’s case, he said, “it’s good to see that the networks are acting so responsibly in this case by refusing to show this barbaric action.”

Twitter removes images of beheading

Beheading of American journalist James Foley recalls past horrors

CNN’s Laurie Segall and Samuel Burke contributed to this report.