Story highlights

The Ferguson, Missouri, riots renew painful talks parents give young sons

Fatal shootings of young black men complicates how families raise a son

'I stress to him his appearance is important,' dad tells son, 15

'Why should I be afraid to walk down the street?' teen asks

From parent to son, uncle to nephew, grandparent to grandson, there’s a raw, private conversation being re-energized in America in the wake of violence in Ferguson, Missouri.

It’s an intimate lecture that most Americans won’t know, but parents like Kelli Knox of Southern California know it too well because it begins the loss of their children’s innocence and exposes them to a painful national truth that’s increasingly become a matter of life or death.

As challenging as parenting is, black families in particular are assuming more burdens: At kitchen tables and in living rooms, they hold honest talks with their boys about how life can be different for them and what they ought – and ought not – to do in public, especially near police.

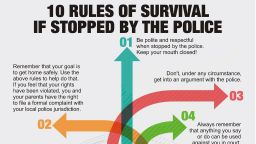

Think twice about wearing a hoodie. Pull up your pants. Shut your mouth around police. Swallow your pride. Don’t drive with more than three friends. And keep your hands where they can be seen.

These are just a few examples of the rules that parents tell their young black sons – and sometimes daughters – about how to stay safe. Though stark and blunt, the admonishments follow a trend of violence that touches upon the most fiery issue in America: race.

The 2012 shooting death of Trayvon Martin, the 2013 police shooting of a North Carolina man who was apparently seeking only help and this week’s riots against Ferguson police – these sensational cases all involve shooting victims who were unarmed, young black men.

My son knows he could be Trayvon

“I’ve had this conversation with my son since middle school on how to behave,” said Knox, 46, of Inglewood, California. “When the police come, this is what you do. This is how you speak to them. Do not get into a power struggle. Listen to them. If they are trying to give you a ticket, get the ticket. Because it’s not worth it. It’s just not worth it.”

A ‘sad’ day and time

Whether at reunions, picnics, or the mall, families and friends make it a point to apprise sons, nephews or grandsons of what Knox calls “the rules of engagement” for young black men when they encounter police or other figures of authorities.

Robert Spicer tells his eldest child, Crishawn, 15, to be aware of even how he dresses.

“I stress to him his appearance is important, the way he conducts himself, the way he talks to people,” said Spicer, 44, a tow truck driver who lives Los Angeles.

His wife, Lashon, 42, said the California couple worry about their four children every day.

“You don’t know what’s going to happen between dropping them off and them coming home,” she said.

Brent Paysinger, a Church of God in Christ pastor in south Los Angeles, and his wife, Andrea, constantly urge caution with son Isaiah, 15.

“Basically you have to separate yourself in this day and time. It’s sad but it’s true. They profile you just by first appearances,” Andrea Paysinger said.

Such talks have taken on greater urgency in the wake of the Ferguson police shooting and killing of unarmed 18-year-old Michael Brown last week, one expert said. Witnesses say Brown was holding his hands in the air when he was fatally shot.

The hashtags #IGotTheTalk and #IGaveTheTalk trended on Twitter this week, with parents and children sharing on social media when they had such tough conversations.

“Here we go again” was the reaction of education expert Steve Perry about the Ferguson incident.

“We have another instance in what an African-American man loses his life because of something that seems like it went awry,” Perry said.

As a principal of a nationally recognized magnet school in Connecticut and an African-American father, Perry said it’s important for parents to explain to youths the expediency of just getting home safely.

“If you have a black son, and you’re not taking the time to explain to him what he needs to do when he’s out in the streets, how he needs to dress and how he needs to act and explain to him that he actually does have a target on his back – then you are not doing your job as a parent,” Perry said.

Other experts say other minority families should hold such a talk with their children.

“The bottom line is we are living in a post-Trayvon Martin, post-Zimmerman trial world, and any parent of color – Latino or African-American parent – must have these conversations with their children. It is just really reality,” said Sonny Hostin, a former federal prosecutor and legal commentator. “It is the same conversation I think that many parents have about stranger danger; the same conversation that parents have with their children about look both ways before you cross the street.”

A case study

Perry recalled how he, too, was racially profiled by police. He offered the account as a case study in how black youths should respond in such scenarios.

“When the police pull you over, you have to do everything you can do to mitigate the situation to lower the level to just get home,” Perry said. “I’ve been in that situation myself. I was riding home with my wife and kids and I had a hoodie on and I guess I was driving something nice, that I shouldn’t have been driving faster than the police thought I should’ve been driving, and I was pulled over and the police officer got real slick. He said some things to me that I thought were completely inappropriate.

“I said absolutely nothing. I looked forward. I made no fast movements. I did everything I could to just get my family home,” Perry said.

Perry later complained to the officer’s boss and received a written apology, he said.

Perry blamed a broad trend for the way young black men are treated.

“Black males are criminalized from the time we enter the ‘system,’ and I’m talking about school,” Perry said. “From the time children enter the system, African-American males are the most suspended, most punished of any group. Period.”

How children react

The guidance can be difficult for youngsters to swallow.

“I think sometimes I am an African-American man, young man, why should I be afraid to walk down the street and get discriminated against because of the color I am, or the way I am dressed or the way I look?” said Crishawn Spicer, 15.

Not too surprisingly, the boys may not fully appreciate their parents’ caution.

Sometimes, they accept it sheepishly.

“My parents really care about me. That’s what they are there for,” said Isaiah Paysinger, 15. “Some stuff, me being a teenager, I think they are too overbearing on, but this is for my safety. And with this whole situation, the young man who got killed, I see why.”

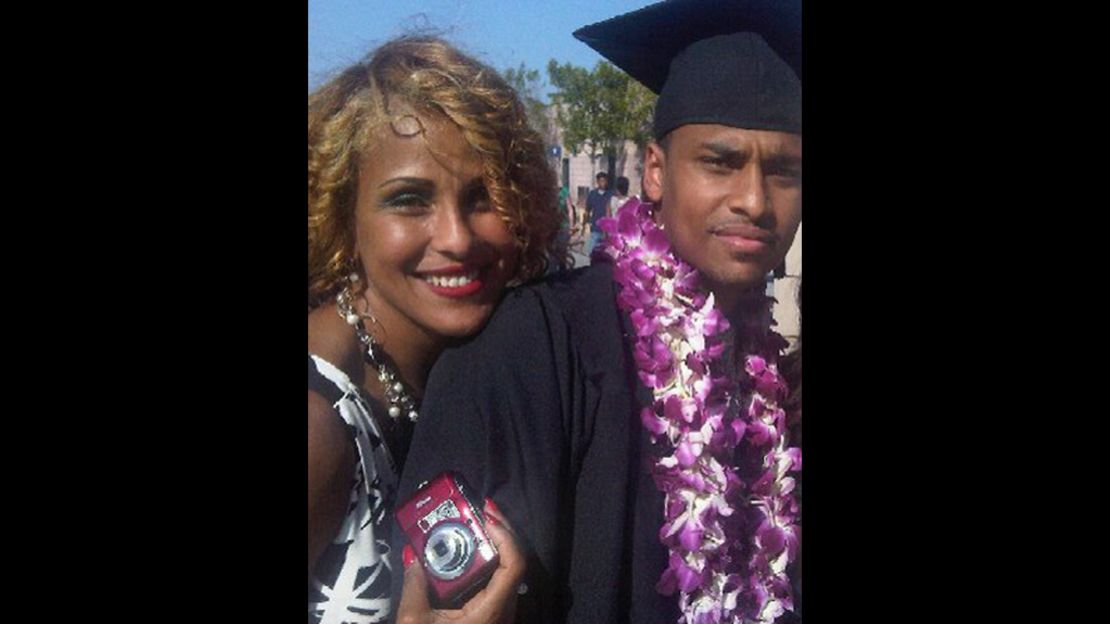

Knox’s son, Joseph, who’s now 26, declined to be interviewed by CNN at first. The subject was too emotional, and he suggested that sometimes his mother may be worrying too much.

Then he changed his mind about the interview.

“I think she has a right to worry. She’s a little bit too worried, but I don’t blame her,” Joseph Knox said.

Trim, athletic, sporting a type of goatee known as the balbo, Joseph Knox said he is a law-abiding working professional. He’s a technician in the hyperbaric chamber at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The parental talks, he now says, are “very necessary.”

“I don’t look like trouble. I don’t dress like it. I went to college and graduated, and I still have problems like the next kid,” Joseph Knox said.

In one example, he was outside his house with his girlfriend when police asked him what he was doing.

“I’m clearly talking to my girlfriend and he says, ‘Why don’t you go crip walk back up into your house,’” he said.

He said nothing, though his initial response was to “go back and forth with him,” he said.

“They want to provoke you but … my mom and my family told me and taught me how to deal with them,” Joseph Knox said. “A kid who maybe didn’t have the same kind of family, he’s going to go argue with the police like it was the next man and that’s where trouble comes.

“It helps to have parents or family to give you an education on how to deal with that stuff,” Joseph Knox said.