Story highlights

- Samuel Moyn: WWI launched debate: can laws of war impose limits how war carried out?

- After WWI, aim was to end war, but in 100 years, aim shifted to making it more 'humane,' he says

- Moyn: Focus now not to end nations' aggression, but to stop atrocity. Vietnam a low point

- Since 9/11, our wars much cleaner, lawful; but WWI idea of 'war to end wars' failed, he says

The guns of August 1914 unleashed a debate that is still with us: Can the laws of war actually impose limits on how war is carried out?

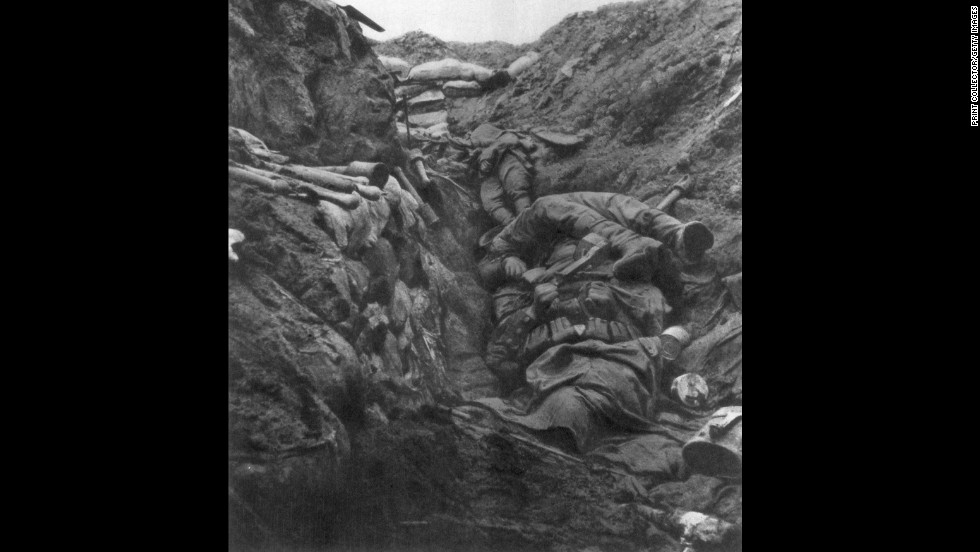

Germany invaded Belgium, violating that nation's neutrality -- which was guaranteed by treaties stretching back to the 19th century. This act horrified the world -- as would the civilian occupation policies that marked German rule in Belgium, Northern France, and elsewhere during the long years of trench warfare.

The question of how much international law should be respected during wartime has resurfaced repeatedly through the 20th century -- in America, it has come up frequently since 9/11, especially surrounding the "torture debate."

Indeed the revelations that American soldiers in Iraq brutalized detainees at Abu Ghraib prison marked a turning point in how Americans regarded the morality of "our" war, and on one level this was nothing new: atrocity has repeatedly stunned Americans throughout their history, and they have sometimes mobilized against it.

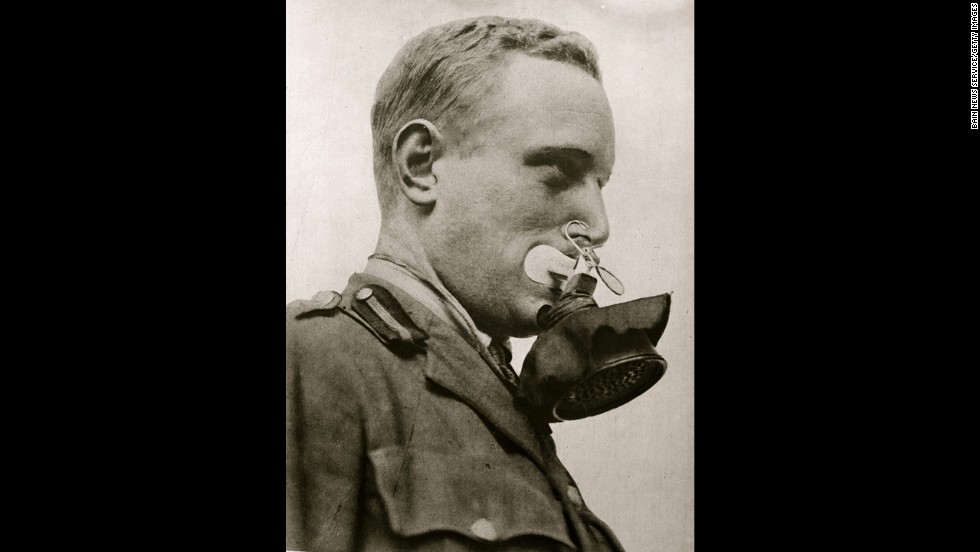

Yet on another level, the years since Abu Ghraib have marked a radical new stage, because of how central law has been to our debates about war: The American government tried to deny that treaties prohibiting torture (from the 1949 Geneva Conventions onward) applied to the global war on terror, but it failed. In fact, over the 20th century, the world took real strides towards the goal of "humanizing war," though perhaps only because the century also made war itself so much worse.

But there is another story about World War I and the legal consequences it set off that is less familiar and more disquieting. It is about a legacy we have lost, rather than one we have realized: that of aiming, through the laws of war, to bring war itself to an end.

World War I, as Paul Fussell famously argued, discredited what Wilfred Owen in a classic poem called "the old lie": that it is sweet and honorable to die for one's country. But what it has meant to shift allegiances from nation to "humanity" has changed drastically over the 20th century among those flirting with wider and cosmopolitan sensibilities. Namely, the highest goal shifted from the abolition to the humanization of war.

When World War I ended, the German Kaiser was very nearly criminally tried. It was only his flight to the Netherlands that made him inaccessible to justice. But it was his aggression, rather than his army's atrocity, that mattered most. There is even evidence that after World War I the phrase "crimes against humanity" -- which now refers to abuses against civilians -- often meant warmongering itself.

In other words, the law would criminalize war, rather than merely make it cleaner. The Nuremberg trials after World War II maintained this focus, attending most to the Nazis' aggressive crimes against peace -- bringing war to the world like the Kaiser had before them -- than atrocities in general or crimes against humanity in particular.

By contrast, our post-9/11 debates around the laws of war have rarely centered on the moral validity or legal propriety of war itself . Rather, from the torture revealed at Abu Ghraib, to drones, and now surveillance, the concern of the mainstream of the American public has centered on how far the executive may go in the pursuit of victory. If law matters, it is to keep the war "humane," rather than to keep it from happening in the first place.

Many survivors of World War I would have viewed this as a drastic constriction of their aspirations and a failure of their aims. Even if it is justifiable, the narrowing of our concerns must be explained.

For Americans, it may have been Vietnam that caused the transformation. That era saw a massive spike in antiwar consciousness, and Americans joined the world in worrying that the country was now forsaking the very legacy of the laws of war it had helped build.

But after that generation's Abu Ghraib -- the My Lai massacre, whose revelation in army photographer Ron Haeberle's images was once equally famous -- a consensus slowly built. What people arguing about war could agree on was that it was immoral and illegal to fight it so brutally. The goal of criminalizing aggression lost traction, and focus on atrocity took its place.

In the years after Vietnam, more and more people signed on to this view. Barbara Keys shows it was after and in response to Vietnam that Americans joined the international human rights movement, which sponsored a Campaign against Torture, which in turn led to a treaty outlawing the practice, setting up the possibility for our torture debate.

Many of the statutes that most constrain the executive in the way it fights, such as the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, were passed in this atmosphere. (Congress also passed laws trying to keep presidents from unilateral military action, especially the War Powers Resolution, but recent history shows it to be a dead letter.)

I find the Vietnam-era debate to be an illuminating point of comparison with our time. If we are honest, we will see that atrocities after America's 1965 escalation in Vietnam then dwarfed atrocities now. It hardly makes whatever violations we have committed excusable, of course, to say so.

The other day, President Barack Obama acknowledged that "the CIA tortured some folks" after 9/11, but the full documentation has remained a political football and neither Democrats nor Republicans want accountability for crimes.

But we should not let our justified outrage over these facts distract from the truth that America's post-9/11 military has fought some of the cleanest wars ever. In particular, compared with the crimes of prisoner detention and aerial targeting in Vietnam (and torture too), America's recent misdeeds have been minor.

One big reason is the U.S. military's own response to Vietnam: After decades of benign neglect or outright disregard, it started to treat the laws of war as real constraints on how it fights.

Consider the decision to target enemies to make sure only combatants rather than civilians are in our crosshairs: Vietnam was more like World War I, with lawyers nowhere to be found, and civilians dying in massive numbers. Today military and other government lawyers play a central role, as the recent controversy over the legal authorization of the drone strike on Anwar al-Awlaki attests.

The long trajectory from World War I has produced a paradoxical situation: We now have real, though insufficient, constraints on war's brutality, and more public discourse than ever about it. But we lack much concern about the goal of eliminating war itself. One legacy of the horrified response to modern war remains alive and well, but the other is forgotten. The "war to end all wars," as World War I has long been known, doesn't deserve that name yet.