Story highlights

- Priya Satia: Unleashing of air power in World War I resonates in drone use today

- Remote killing, surveillance used throughout war theater, but mostly by British in Middle East

- Air power gave British access to remote lands; they'd later use it for colonial policing

- Satia: Today's drones are a new chapter in West's efforts to dominate Middle East

Drones are our latest Frankenstein's monster. But our preoccupation with their novelty -- with the ethical hazards of remote killing and the possible violation, through surveillance, of life and privacy at home -- has obscured their roots in the deadly history of Western aerial control of the Middle East that began in World War I, exactly a century ago.

As we recall the myriad ways in which that epochal war remade our world, it is time also to reckon with its unleashing of air power in the Middle East.

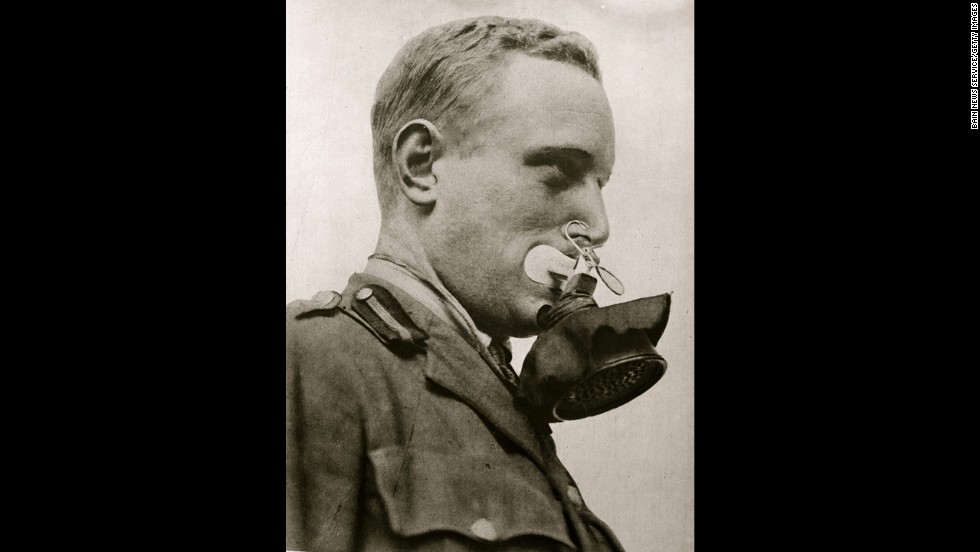

Air power harks back to Civil War-era hot-air balloons and was used all over the theaters of World War I for reconnaissance, bombardment, and aerial combat. However, its potential was most rigorously tested and developed in the British campaign against the Ottoman Empire during that war.

Aerial photography and signaling, the airlift, the aerial trap (bombardment of the head and tail of a column retreating through a canyon) -- all were developed in WWI's Mesopotamia and Palestine campaigns, fought in the area of present-day Iraq and the Arabian Peninsula, north through Syria.

The British fought these campaigns to safeguard the all-important land, air, and sea routes to British India and oil assets in the Persian Gulf. Aircraft were used in bombardments that wrecked trains and in irregular warfare, where they, for example, helped Arab guerrillas fighting the British-backed revolt against the Ottomans communicate and conduct reconnaissance. They were also used in deception strategies, such as in providing air cover to conceal troop movements before the surprise British attack at Megiddo.

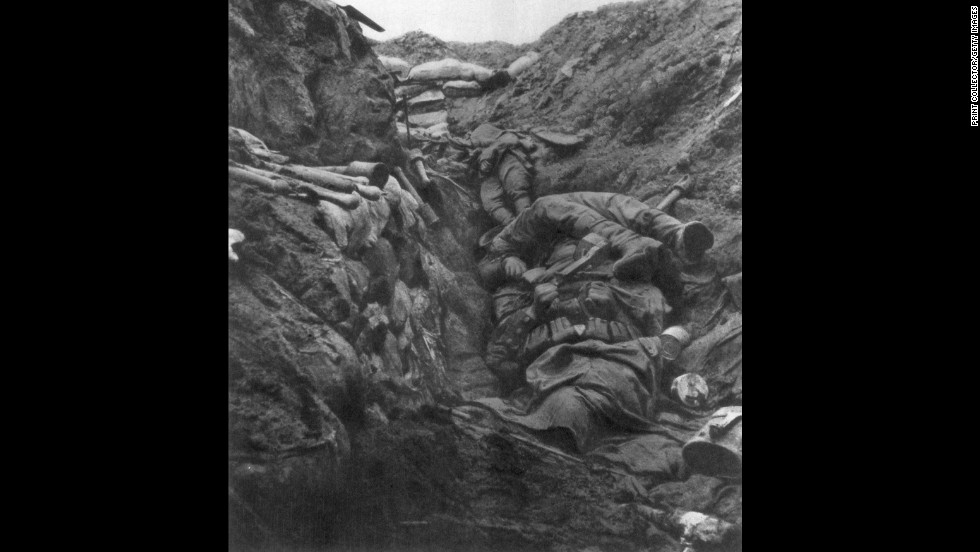

Most significantly, for the history of drones, their uses in colonial policing were discovered there and would echo through the century. When the tribes the British had "liberated" from Turkish rule in the war "got out of hand," aerial bombardment became an instrument of everyday colonial discipline, inspiring "terror in the Arabs," official memos noted approvingly.

Aircraft seemed a panacea for what the British categorized as "tribal" situations. Thus did the postwar British Cabinet declare that it was in the Middle East that "the war ... proved that the air has capabilities of its own." We may have forgotten this past, but in the region, memory of it shapes the response to American drones and airstrikes today.

All this came about because of World War I-era British notions of the particular suitability of air power to the Middle East. Officials who guided the military effort in the region saw it as a land of mystery impervious to ordinary observation. Surveillance aircraft seemed to promise vision beyond the mirages, sandstorms, and distances that made it unmappable in their estimation. Commanders relied on them for "obtaining ... accurate information'' in a land where ''little can be trusted that is seen."

And they provided access to forbidden sites. Conceiving the region as uniformly flat (despite its marshes, mountains and cities), British Arabists assumed it afforded no cover.

In fact, there were real limits to using aircraft even in the desert, but the idea of "knights of the air" providing panoramic surveillance of an inscrutable antique land proved irresistible. So too did the image of aircraft turning Mesopotamia into a hub of modern transportation and thus restoring its status as the cradle of civilization, in some measure redeeming the material and human losses of the war.

British officials made much of the "natural fellow-feeling between ... nomad arabs and the Air Force ... both ... in conflict with the vast elemental forces of nature." Arabs could uniquely endure the violence of bombardment, Britons thought: In a biblical land, tragedy was a "normal way of life" and bombardment understood as an "act of God."

These wartime experiments with aerial bombardment and surveillance produced the postwar "aerial control" regime in the region, a discreet and cheap mechanism for colonial rule in an increasingly anti-imperial world. Because the British thought of the Middle East as a region where all information was suspect and deception was everywhere, they saw casualty counts and accountability for errors -- like bombardment of the wrong town or tribe -- as superfluous.

After the war, the British Royal Flying Corps survived as an independent military service, rechristened the Royal Air Force, because of this role in the Middle East.

The British used the RAF to police the new British territories in the Middle East with aerial surveillance and bombardment. This technique, known as "aerial control," spread to Palestine, Somalia, Yemen, and what we call "AfPak" -- precisely where drones reign today. It was in Iraq and Afghanistan that British airmen in World War I and the interwar period -- including Arthur Harris, zealous head of Bomber Command in World War II -- acquired the experience they applied in the next world war.

The British state propagated a myth of successful air control in the Middle East, but the technique never really worked. The British presence provoked insurgency and undermined local governments until the Iraqi revolution of 1958, when the United States began its interventions in the region.

Those who live under drones see them as the latest chapter in a long history of Western efforts to dominate the region with air power. The "Reaper" dropping "Hellfire" missiles again styles bombardment as a biblical fate. Today, too, casualties are not published and all the dead in a strike zone are presumed to be militants.

We would do well to recall this aerial history of the very region where drones found their initial justification. Remote piloting was always an objective of aerial warfare; drones follow rocket warfare and cruise missiles.

Aerial warfare was always about minimizing casualties on one side and pursuing empire discreetly. Drones may be more precise than earlier aircraft, but the principle of cowing a population with ubiquitous surveillance and exemplary violence, without arousing the ire of a democratic public at home, remains their underlying principle. So, too, do notions of the Middle East's particular suitability to aerial control.

In our shock at the new, we have overlooked these Great War roots. In their recovery lies crucial insight into why an aerial strategy will fail in the Middle East, piloted remotely or on the spot.