Editor’s Note: This is the sixth in a series on the legacies of World War I appearing on CNN.com/Opinion in the weeks leading up to the 100-year anniversary of the war’s outbreak.Ruth Ben-Ghiat is guest editor for the series. Ruti Teitel is the Ernst C.Stiefel professor of comparative law at New York Law School and visiting fellow at the London School of Economics. She is the author of Globalizing Transitional Justice.

Story highlights

Ruti Teitel: Versailles Treaty that ended WWI hostilities imposed huge cost on Germany

This assigning of "collective guilt" likely helped Hitler exploit German humiliation, foment WWII

Teitel: Backfire changed how global community punishes war crimes: individuals, not nations

Teitel: Today age of "smart sanctions," global tribunals, such as in response to Russia, Syria

It’s well known that the decision to impose collective guilt on Germany at the end of the First World War was a fateful one. But even today, 100 years after the start of the Great War, the fallout from the Treaty of Versailles affects U.S. foreign policy –from Europe to the Middle East, from Ukraine to Syria.

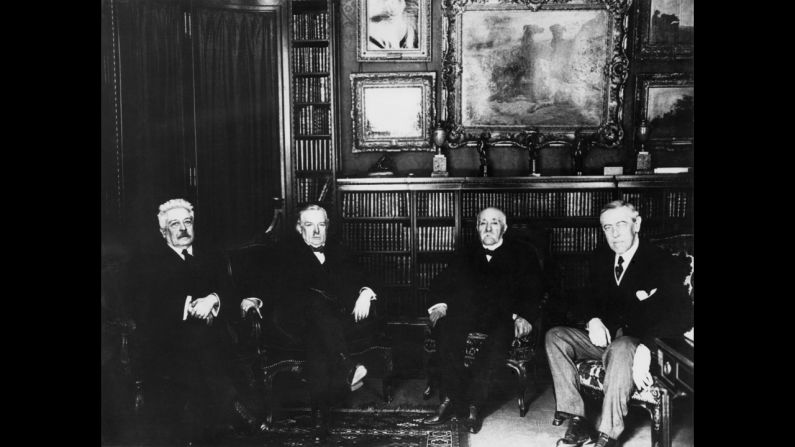

At the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, the signing of the Treaty of Versailles ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. Article 231 of the treaty, the notorious War Guilt clause, required “Germany (to) accept the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage” during the war.

The treaty forced Germany to disarm, make substantial territorial concessions and pay reparations to certain countries. The total cost was 132 billion marks, or $31.4 billion, roughly equivalent to $442 billion today.

At the time, economists, notably John Maynard Keynes, warned that the victors were imposing a brutal “Carthaginian peace,” a reference to the peace imposed on Carthage by Rome 2,000 years before, which amounted to a complete crushing of the enemy and which also mandated the payment of constant tribute.

Opinion: How a century-old war affects you

Germans’ feelings of victimization and hatred of Versailles were soon exploited by Adolf Hitler. Many analysts now conclude that this miscarriage of justice, this experience of collective punishment, backfired and helped pave the road to World War II.

War's legacy

WAR’S LASTING LEGACY

The discrediting of the collective guilt imposed at Versailles would result in a major reorientation in international law and policy, changes that we live with today. Guilty nations have been replaced by war criminals, prosecuted and punished by international tribunals.

After World War II, the Nuremberg trials for “crimes against the peace” were justified not in retrospective terms but in forward-looking ones–namely the peace of future generations. The postwar trials reflect that even individual responsibility is understood today less in terms of retribution than deterrence.

Opinion: When chemical weapons killed 90,000

This new view of responsibility has become more and more pronounced in recent years, to the point where individuals may be held responsible, but nations are absolved.

In 1995, at the first public indictment proceeding of the architects of the Balkans ethnic cleansing policy, Chief Prosecutor Richard Goldstone declared that the proceeding of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia would establish a “public record” to “assist in attributing guilt to individuals …and in avoiding the attribution of collective guilt to any nation or ethnic group.”

Opinion: The mighty women of World War I

In the words of the prosecutor in the very first case in the court against a member of the Serbian paramilitary force, Dusko Tadic, accused of horrendous persecution of Muslims in the Omarska detention camp, “Absolving nations of collective guilt through the attribution of individual responsibility is an essential means of countering the misinformation and indoctrination which breeds ethnic and religious hatred.” (Tadic was convicted of, among other things, crimes against humanity.)

Such international justice via individual accountability would break “old cycles of ethnic retribution” and thus by displacing vengeance would advance reconciliation. The court was considered to be critical to restoring the peace in the region.

Opinion: How World War I gave us ‘cooties’

This emphasis on individual responsibility was crowned with the establishment of the permanent International Criminal Court in 2000. Deterrence is the clear goal in the ICC preamble. It declares that “during this century millions of children, women and men have been victims of unimaginable atrocities that deeply shock the conscience of humanity,” and expresses the Court’s determination to “put an end to impunity for the perpetrators of these crimes and thus to contribute to the prevention of such crimes.”

The United Nations also shifted away from collective punishment toward smart sanctions that target individuals with economic and other punitive measures, ordered by the U.N. Security Council, and not entire countries. Indeed, one can see how this shift affects policy today toward Russia over its meddling in Ukraine and toward Syria, where in both instances international response has taken the form of international sanctions as well as international criminal justice, both responses eschewing collective punishment.

Opinion: The ‘bionic men’ of World War I

In Syria, for example: This May the French sponsored a resolution to Security Council members that would have given the ICC jurisdiction over crimes against humanity and war crimes committed in Syria during its ongoing civil war. The United States was among the many Security Council members to support the referral, but the action would ultimately be blocked by China and Russia in a Security Council vote earlier this summer.

Likewise, the Russian incursion into Crimea might in the past have raised Cold War tensions and provoked a collective punishment on the entire nation, but the response of the United States and the European Union illustrates the approach of individualizing responsibility: While the sanctions have been progressively expanded and tightened in response to ongoing events (the latest being the downing of the Malaysia Airlilnes jet over Ukraine), the companies and individuals targeted have been clearly selected on the basis of their proximity– those who may be making or supporting the specific decisions relating to Ukraine.

Still, such sanctions can only work if the international community hangs together, and the temptation for the world’s major military powers to revert to the rhetoric of retribution can be almost overwhelming—one might say even that the Obama administration fell victim to it late last year calling for accountability and an end to impunity for the Bashar al-Assad regime as a basis for U.S. military intervention.

But the anniversary of the Great War and its Armistice can serve as a reminder that retribution against a people or society breeds a sense of injustice and indeed may be intrinsically unfair. Rather than a just settlement to war, it may serve only to perpetuate conflict.

Photo blog: WWI: The Golden Age of postcards

Read CNNOpinion’s new Flipboard magazine