Vital Signs is a monthly program bringing viewers health stories from around the world.

Story highlights

40 years after its discovery, there are no licensed treatments or vaccines for Ebola

Ethically, a vaccine for Ebola can only be trialled for effectiveness during an outbreak

Vaccines are better trialled in high-risk groups, including healthcare workers, say experts

Ebola virus disease is sweeping across West Africa in the largest outbreak of the virus to date. Mortality rates are currently at 60% in a disease where up to 90% of infected people can die. But despite this lethality there remain no licensed treatments or vaccines available, nearly 40 years after the disease was first discovered.

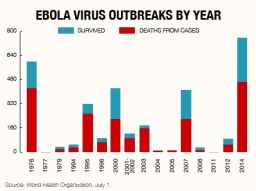

In March, Ebola was reported for the first time in Guinea, West Africa, in districts that border neighboring Liberia and Sierra Leone. This proximity meant that unlike previous outbreaks in other parts of Africa, the usually remote Ebola virus had the opportunity to cross borders. With residents migrating back and forth, it did just that. Four months later the outbreak has reached unprecedented scales, with 1,093 people infected and 660 deaths attributed to the virus.

“This is clearly an outbreak across international borders and it has not been handled properly,” explains David Heymann, professor of infectious disease epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), who was on-site at the first human Ebola outbreak in 1976.

He says the 24 known outbreaks of Ebola to date have shown that it should be easily controlled. “It’s not rocket science to control these outbreaks but instead basic epidemiology: infection control, hygiene practices, contact-tracing and safe burial practices,” says Heymann of the virus, which is transmitted through contact with bodily fluids. “Ebola is its own worst enemy, it’s too lethal and cannot sustain its own spread.”

But whilst it should be easily contained, this time something has gone wrong. The Guinean and Liberian capital cities were reached exposing many more to the virus and making those infected and their contacts harder to trace and isolate. The outbreak has been described as “out of control” by Doctors without Borders – so why is there no other approach?

Opinion: Why Ebola epidemic is spinning out of control

The usual response in disease outbreaks is to use drugs to treat those infected and stop them transmitting to others, in combination with vaccines that protect those exposed and slow down, or halt, the spread of a virus through a population by enabling herd immunity. But there are no licensed drugs or vaccines for use against Ebola as its periodic, remote and usually small-scale nature means there has not been a big enough market, nor the ability to conduct large-scale trials in humans exposed to the disease.

The biology of the virus also makes it challenging to develop vaccines that create a strong enough immune response; the occurrence of multiple forms of the virus means an immune response is needed against all of them, and Ebola’s ability to replicate rapidly means it could equally rapidly evolve resistance to the vaccine.

Despite these challenges, there are vaccines being developed by a range of organizations, including the vaccine research center at the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) – and some argue that an outbreak is the perfect time to trial them.

“It would be unethical not to acknowledge that potential new treatments could both save lives and reduce transmission in this and future outbreaks,” says Dr Jeremy Farrar, director of global charitable foundation the Wellcome Trust. Farrar has recently called for new approaches to be used in controlling the outbreak as no other opportunity will enable the further development of new treatments or vaccines.

“Any new intervention must have preclinical safety and efficacy data and Phase I safety data in healthy volunteers,” he says describing the slow progression of phases involved in pharmaceutical development, “But ultimately there can be no Phase II (vaccine efficacy)data in Ebola other than that acquired during an epidemic.”

Read: What is Ebola and why does it kill?

Peter Piot, director of the LSHTM, who co-discovered Ebola during its first outbreak, agrees with Farrar. “In general I believe that this continuing outbreak is a rare opportunity to evaluate the effectiveness of experimental drugs,” he says, but stresses, “as long as all ethical standards are respected, and as long as it does not create more problems for controlling the outbreak, since medical experiments may decrease even more trust in health authorities and add to hostility to healthcare workers.”

Piot is referring to resistance from affected communities towards healthcare workers and health officials who enter their villages dressed in astronaut-like quarantine clothing and ask them to change their cultural practices such as burials, where the traditional cleaning of bodies puts those mourning at risk of transmission. Long-standing mistrust exists towards governments and ministries of health, leading to healthcare staff having rocks thrown at them, being threatened by machetes and facing general aggression, according to a World Health Organization (WHO) spokesperson.

Tensions between those controlling the outbreak and those affected by it mean trialling vaccines in outbreak communities is not supported by WHO officials on the ground. “Using an experimental vaccine on human beings in the middle of an outbreak in this case would not be ethical, feasible, or wise,” according to the WHO. But there remain other avenues.

“The vaccines are likely safe and effective but aren’t used by public health teams and they won’t use them without adequate trials,” explains Dr Peter Walsh, from the University of Cambridge, who is developing vaccines for use in non-human primates such as chimpanzees and gorillas who are also victims of the virus. Walsh’s vaccines have shown a good immune response when trialled in chimpanzees and he suggests trialling human vaccines incrementally in healthcare workers rather than the mass population.

“Healthcare workers are at the greatest risk and are hubs of infection who are likely to spread it to others,” he says. “The risk of dying from the vaccine is tiny compared to dying from Ebola and unlike communities, healthcare workers would understand the risks better and should be able to give informed consent.”

Read: Ebola doctor contracts the virus

This approach is supported by the NIAID, whose Ebola vaccine programs have progressed the furthest. “We are supporting a number of vaccines and they are all in a roughly similar position and getting ready for Phase I trials for safety,” says Dr Mike Kurilla, director of their Office of Biodefense Research Resources and Translational Research.

“If these make it through testing what we’re likely to see in future outbreaks is healthcare workers and outbreak investigators taking the vaccine under informed consent,” Kurilla explains. “Working with those at the highest risk will enable you to see if the vaccine has an impact.”

It is too late in this outbreak for vaccines to have enough of a preventative impact, but Ebola will emerge again in the future. If safety can be proven, the stockpiling of vaccines could improve the outcome of future outbreaks.

“Vaccines enable a preparative framework to be established rather than a reactive one,” explains Heymann. “But firstly it must be shown to be safe in humans.”

The ability to control future epidemics may depend on it.

Opinion: Why Ebola epidemic is spinning out of control