Story highlights

1974 featured some much-maligned pop songs but great movies

Year was fatiguing, with Nixon, Vietnam finally leaving stage

Pop was in statis at the time, getting segmented; movies reveled in chaos

Some patterns still borne out today

We had joy. We had fun. We had loathing.

In 2006, this website conducted a highly unscientific survey to find the worst song of all time. One year stood out in its bad-song production: 1974.

That included two of the top five – Terry Jacks’ “Seasons in the Sun” and the runaway top choice, Paul Anka’s “Having My Baby” – and several more leading vote-getters, including Paper Lace’s “The Night Chicago Died,” Maria Muldaur’s “Midnight at the Oasis” and Bo Donaldson and the Heywoods’ “Billy, Don’t Be a Hero.”

Summer rewind: Looking back at 1974

And yet the year wasn’t a pop-cultural wasteland. Far from it, as a matter of fact. As a year for movies, 1974 is often ranked as the best since the sainted slate of 1939.

The releases included best picture winner “The Godfather Part II,” “Chinatown,” Mel Brooks’ one-two punch of “Blazing Saddles” and “Young Frankenstein,” not to mention disaster movies, revenge flicks, conspiracy thrillers and family features.

It was enough to make you kiss your movie theater while kicking your radio.

These days, that kind of movie mix is almost unimaginable, when studios race to dominate box-office weekend tallies with comic-book blow-‘em-ups. And music? Depends whom you ask, though it has certainly splintered over the last four decades.

What gives?

‘I think the country was exhausted and traumatized’

It’s worth a look back at an unbeloved year.

With President Richard Nixon’s resignation, the wind-down of the Vietnam War, the end of the Arab oil embargo, the rotting of New York, bad weather outbreaks and failing governments, it was a fatiguing time.

“I think the country was exhausted and traumatized by all the hubbub that was going on,” says UCLA professor Mitchell Morris, the author of “The Persistence of Sentiment,” a book about 1970s pop music.

In addition, the events “took the wind out of the sails” of the counterculture, which had been setting musical trends since the mid-1960s, says Georgia Tech performance studies professor Philip Auslander.

Into the breach came escapist and comforting songs appealing to a new generation.

Escapism and comfort often get a bad rap in pop music, Morris observes. If you’re a teenager or college student trying to impress your friends and form your own cool identity, the last thing you want to confess is a fondness for “Seasons in the Sun.” But that sort of feeling is underrated, he observes.

“One of the important roles that rock ‘n’ roll has played is it’s the music you can use to piss off your parents,” he says. “(But) sometimes music is for solace. We don’t like things that too obviously want to be liked. But what’s wrong with wanting to be liked?”

Reinforcing confusion

At the movie theater, on the other hand, a lot of the hits were anything but comforting. Instead, they reinforced the confusion of the times.

One reason is that the movie counterculture had risen to positions of power while the old studio system was falling apart. Directors such as Francis Ford Coppola and William Friedkin liked to shake up their bosses – and the audience.

“There’s sort of this brief period where Hollywood studios are willing to take a chance on smaller-budget, more independent-minded films, mainly trying to reach out to the countercultural audience that had emerged during the late 1960s,” says Rodney Hill, a film professor at Hofstra University.

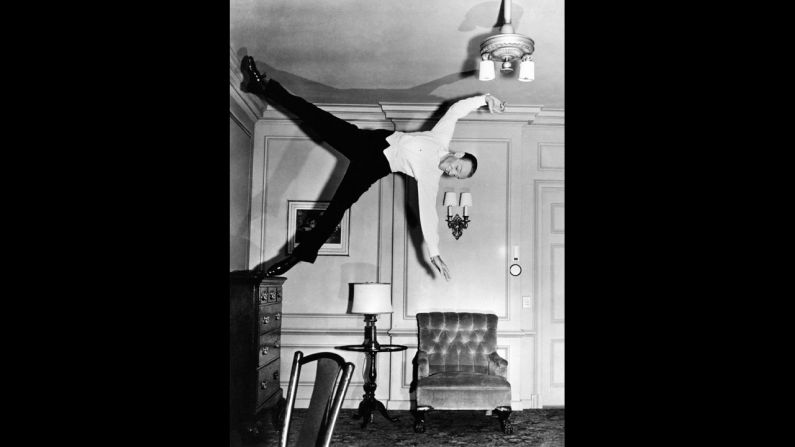

That audience had made hits of such films as “Easy Rider,” “The Last Picture Show,” “The French Connection” and “American Graffiti,” among many. In fact, Coppola’s original “Godfather” (1972) – a gangster epic with some New Hollywood twists – was the highest-grossing film ever at the time.

The burst of creativity reached a peak in 1974 with a number of films that were both critically praised and financially successful. Coppola’s “Godfather Part II,” despite its three-hour-plus running time and complicated structure, was the fifth biggest-grossing film of the year. Roman Polanski’s “Chinatown,” a hard-boiled Los Angeles mystery, and Martin Scorsese’s “Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore,” about a single mother’s attempt to build a life, also finished in the top 20. Brooks’ comedies “Blazing Saddles” and “Young Frankenstein,” the first as anarchic as the latter was meticulous, were No. 1 and No. 3.

The year’s other hits included the conspiracy thriller “The Parallax View,” the vigilante drama “Death Wish,” Burt Reynolds’ prison comedy “The Longest Yard” and the gritty “The Taking of Pelham One Two Three.”

‘Boy, do we need it now’

However, years are never that simple.

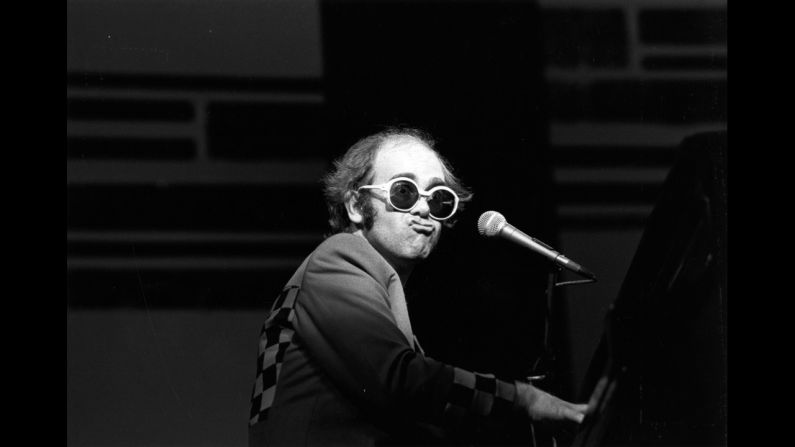

Pop music had more variety than its bad-music boosters might remember.

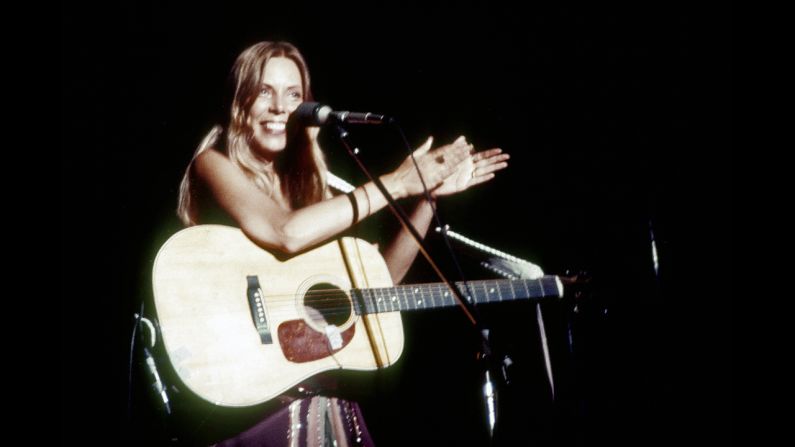

Joni Mitchell had her biggest success with the album “Court and Spark.” Philadelphia International Records had big hits with the Spinners, O’Jays and the eventual theme to “Soul Train,” “TSOP (The Sound of Philadelphia).” Stevie Wonder was at his “Fulfillingness’ First Finale” zenith.

And movie audiences still hungered for old-fashioned pleasures.

Disaster films, the all-star forerunners of today’s CGI destruct-o-ramas, had both traditional heroes – Steve McQueen’s fire chief in “The Towering Inferno,” Charlton Heston’s pilot in “Airport 1975” – and the latest in special effects.

There were also heartwarming, family-friendly hits, including “Benji” and “The Life and Times of Grizzly Adams,” two low-budget, no-star successes aimed at Middle America.

The slogan for “That’s Entertainment,” a hit collection of MGM musical clips, summed up the feeling: “Boy, do we need it now.”

But even “That’s Entertainment” wasn’t without its 1974 ironies, says Peter Alilunas, a media studies professor at the University of Oregon.

“MGM was falling apart. In that movie (the stars are) literally touring the destroyed back lot,” he says.

The personal touch

What can we make of all this?

If 1974 did anything, it was lay the groundwork for the future.

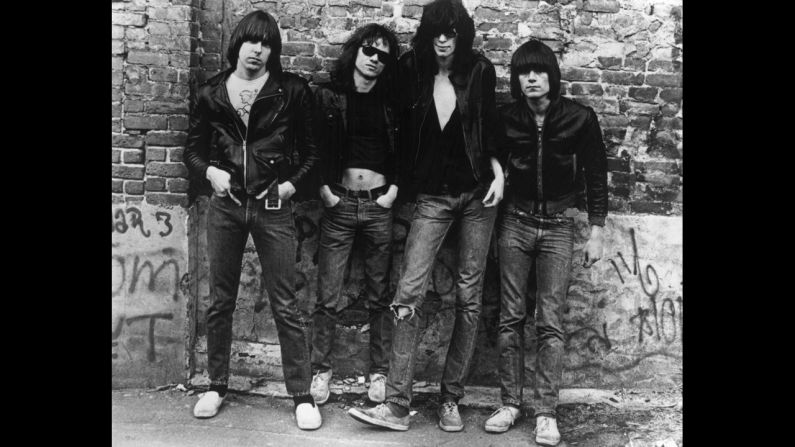

The music business was getting shaken up. Disco started making inroads. Punk was on its way, being birthed in downtown New York.

“The paradigms are about to shift,” says Georgia Tech’s Auslander, pointing out that the year’s anomalies wouldn’t be anomalous for long.

And movies? They were going the opposite direction, getting ready to embrace the escapist blockbuster and wide openings. First came 1975’s “Jaws” and then, two years later, 1977’s “Star Wars.” The suits reasserted control and the days of the New Hollywood ended.

“The studios are reminded, with one movie we can make as much profit as we do with all those others,” says Hofstra’s Hill.

The shift continues to play out today. In the blockbuster era, it’s become increasingly rare for a dialogue-heavy drama or awards-season favorite to break through.

Tentpoles falling, ‘Gravity’ rising, money spinning: The year in movies 2013

The music business, on the other hand, has gotten more chaotic and splintered. Whatever: Grumblers can take refuge in micro-genres and, thanks to their Pandora recommendations, never have to listen to the kind of variety AM Top 40 – which was fading in 1974 – used to symbolize.

Do you remember rock ‘n’ roll radio?

That’s one kind of personalization. But what 1974 offered was a different kind, says Morris. Great filmmakers were following their muses and doing well. And heard today, even its much-maligned music has its charms, he says.

“There’s a sense that (the artists) haven’t done their market research,” he says. “They don’t know what people necessarily want, so you get things that are very quirky at times.”

That season, you might say, is all gone.