Story highlights

Rebels have downed Ukrainian planes flying at high altitudes

A pro-Russian rebel commander shows off anti-aircraft missiles

The border region with Russia is very porous, unguarded in many places

Some contend that larger weapons have come into Ukraine from Russia

Under a blazing sun in early June, a group of pro-Russian rebels in eastern Ukraine were digging amid pine woods near the town of Krazny Liman.

Their grizzled commander was a bearded man in his 50s who would not tell us where he was from, but acknowledged that he wasn’t local. He was proud to show off his unit’s most prized possession – a truck-mounted anti-aircraft unit that was Russian-made.

He told us the weapon had been seized from a Ukrainian base.

A few miles away, in the town of Kramatorsk, rebel fighters displayed two combat engineering tanks they said they had seized them from a local factory. Eastern Ukraine has long been a center of weapons production. They had parked one of the tanks next to the town square.

These were just two instances of how the rebels in eastern Ukraine were steadily adding more sophisticated weapons to their armory, including tanks, multiple rocket launchers – and anti-aircraft systems.

In early June, they began to target Ukrainian planes and helicopters, with some success.

The day after we met the commander in the pine woods, an Antonov AN-26 transport plane was brought down over nearby Slovyansk.

Several Mi-8 and Mi-24 helicopters were also hit in this period, as was an Ilyushin IL-76 cargo plane near Luhansk – it is about the size of a passenger jet.

Forty-nine military personnel were killed when the IL-76 crashed short of the airport.

For the most part, these aircraft were flying at relatively low altitudes, and were targeted by shoulder-launched SA-7 missiles and anti-aircraft guns. The pro-Russian rebels had taken control of several Ukrainian military depots and bases and stripped them of their weapons.

The SA-7 was standard Soviet issue. Relatively easy to operate, it is effective to altitudes of some 2,500 meters (8,000 feet).

But it and ZU 23-2 anti-aircraft batteries, which rebel units also obtained, are a world away from the SA-11 or “Buk” system that seems increasingly likely to have been used to shoot down Flight MH17 on Thursday.

Stealing a Buk

Could the pro-Russian rebels have acquired a serviceable Buk from a Ukrainian base and operated it? The evidence is circumstantial; a great deal of Ukrainian military hardware is in poor condition or redundant.

But on June 29, rebels raided the Ukrainian army’s A-1402 missile facility near Donetsk. Photographs show them examining what they found.

The Russian website Vosti ran an article the same day titled “Skies of Donetsk will be defended by surface-to-air missile system Buk.”

The article claimed: “The anti-air defense point is one of the divisions of the missile corps and is equipped with motorized “Buk” anti-aircraft missile systems.”

Peter Felstead, an expert on former Soviet military hardware at Janes IHS, says that “the Buk is in both the Russian and Ukrainian inventories, but it’s unclear whether the one suspected in the shoot-down was taken by rebels when they overran a Ukrainian base, or was supplied by Russia.”

He told CNN that the Buk “would normally operate with a separate radar that picks up the overall air picture. This was almost certainly not the case with MH17,” making it more difficult to identify the target and track its course.

Among the pro-Russian rebels are fighters who served in the Russian army. It is possible that some were familiar with the Buk, but Felstead agrees with the U.S. and Ukrainian assessment that Russian expertise would have been needed to operate it.

“The system needs a crew of about four who know what they’re doing. To operate the Buk correctly, Russian assistance would have been required unless the rebel operators were defected air defense operators - which is unlikely.”

It is now the “working theory” in the U.S. intelligence community that the Russian military supplied a Buk surface-to-air missile system to the rebels, a senior US defense official told CNN Friday.

Russia has denied that any equipment in service with the Russian armed forces has crossed the border into Ukraine. And Aleksander Borodai, the self-described prime minister of the Donetsk People’s Republic, said Saturday his forces did not have weapons capable of striking an aircraft at such a high altitude.

But someone in the border region where eastern Ukraine meets Russia has been using an advanced anti-air missile system.

Late Wednesday, the day before MH17 was presumably hit, a Ukrainian air force Sukhoi Su-25 combat jet was shot down close to the border with Russia.

The Ukrainian Defense Ministry told CNN that the plane was flying at 6,200-6,500 meters (about 21,000 feet) and was hit near a town called Amvrosiivka, which is only some 30 kilometers (20 miles) from where MH17 was hit and 15 kilometers (10 miles) from the border with Russia.

The Ukrainian military alleged the missile had been fired from Russian territory. It was the first time that a combat jet flying at high speed had been hit and came two days after an AN-26 – flying at a similar altitude in the same area – was shot down further north, in the Luhansk area.

Smuggling on the black roads

The Russian Defense Ministry said Friday that weapons could not be smuggled across the border “secretly.” But they can.

By early June, rebels controlled several crossings along a stretch of border more than 200 kilometers (125 miles) long. The border area is open farmland that was neither patrolled regularly nor even marked in many places.

Dozens of unmonitored tracks known as black roads – because they have been used for smuggling – cross the border. Additionally, the Ukrainian border guard service was in disarray after an attack on its command center in Luhansk early in June.

On the road east toward the border through the town of Antratsyt there was no sign of a Ukrainian military or police presence. The pro-Russian rebels had already begun to bring across heavy weapons at that point.

A CNN team visited the border post at Marynivka in June, soon after a five-hour firefight involving border guards and members of the self-declared Vostok battalion of rebels who had been trying to bring over two Russian armored personnel carriers.

They had been abandoned during the battle.

The unknowns are these: Just how much weaponry has been brought in from Russia, how was it obtained, and did it include the SA-11 Buk?

In June, the U.S. State Department claimed that three T-64 tanks, several rocket launchers and other military vehicles had crossed the Russian border. Ukraine made similar accusations, saying the weapons had gone to Snezhnoe, a rebel stronghold close to where MH17 came down.

The State Department said the tanks had been in storage in south-west Russia, suggesting collusion between the Russian authorities – at some level – and the rebels. It said at the time that the equipment held at the storage site also included “multiple rocket launchers, artillery, and air defense systems.”

It added, notably, that “more advanced air defense systems have also arrived at this site.”

Moscow rejected the claims as fake.

NATO has also released satellite images which, it said, showed tanks in the Rostov-on-Don region in Russia early in June, before they were taken to eastern Ukraine. The tanks had no markings.

Even so, some experts, such as Mark Galeotti at New York University’s Center for Global Affairs, say the evidence is largely circumstantial. NATO’s images did not show the tanks actually crossing into Ukraine.

Wherever they came from, Russian language websites soon featured calls for people with military skills to call a number associated with the separatist Donetsk People’s Republic if they could help operate or maintain the tanks.

One answered, “I served in the military engineering academy…and am a former commander in the intelligence.”

But the separatists’ greatest vulnerability was always from the air.

The Ukrainians had already shown, in driving them away from the Donetsk airport at the end of May, that they could use airpower to devastating effect. And they had begun to fly at higher altitudes to avoid shoulder-launched missiles.

To hold what remained of their territory, the pro-Russian rebels needed to be able to challenge Ukrainian dominance of the skies.

Whether they received help from across the border to do so, and in what way, is the question that governments around the world want answered.

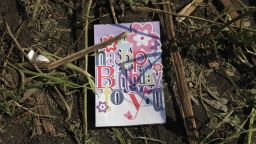

READ: Is this any way to secure a plane crash scene?

READ: Who should investigate MH17 crash?

READ: Athlete, soccer fans, vacationing family among Malaysia Airlines crash victims