Story highlights

Miranshah remains empty after Pakistan military operation in North Waziristan

The region had become "a hub and safe haven" for militants, says army commander

North Waziristan pummeled by air strikes before ground troops moved in

New militant group claims several parts of Waziristan are under its control

In a tea shop in Miranshah, a dusty town in northeastern Pakistan, an empty kettle hangs on a hook waiting to be used, while flies hover over baskets piled high with sweetmeats drying out in the July sunshine.

The surrounding streets are unusually quiet – no children playing, no old men selling fruit, no whir of machinery from local workshops. The buzz of life has been replaced by deathly silence in the largest town in Pakistan’s troubled North Waziristan. Much of it now lies in ruin, its population nowhere to be seen.

In a rare visit organized by Pakistan’s military, I was one of the few journalists transported into the region where the army has been waging a full-scale ground offensive against militants since mid-June. The operation has been named Zarb-e-Azb after a famous sword of the prophet Muhammad.

READ: Major Pakistan offensive aims to ‘finish off’ militants

Maj. General Zafar Khan, the commander of the Pakistan army’s 7th Division and the man in charge of the operation, told CNN that in the months leading up to campaign, the region had become “a hub and safe haven” for militants – foreign and local – in Pakistan.

For almost three weeks, North Waziristan, a mountainous region bordering Afghanistan, was pummeled by a series of air strikes before ground troops moved in. According to Khan, 80% of Miranshah and its surrounding areas have been cleared of militants. Unfortunately, the local population appears to have been cleared too.

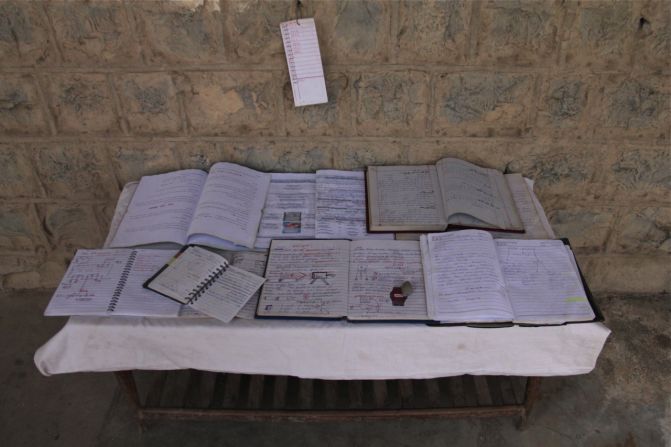

The head of Pakistan’s Inter Services Public Relations (ISPR), Maj. General Asim Bajwa, guides us through various compounds recovered in the town, which is now back under military control. Leaving the 7th division base, we’re driven through a land of beige, past villages such as Machis, which has been hit by drone strikes and now lies abandoned. Soldiers stand guard outside a suspected al Qaeda compound near the village. According to Bajwa, recovered pamphlets and papers indicate it was used by fighters affiliated with the terror network.

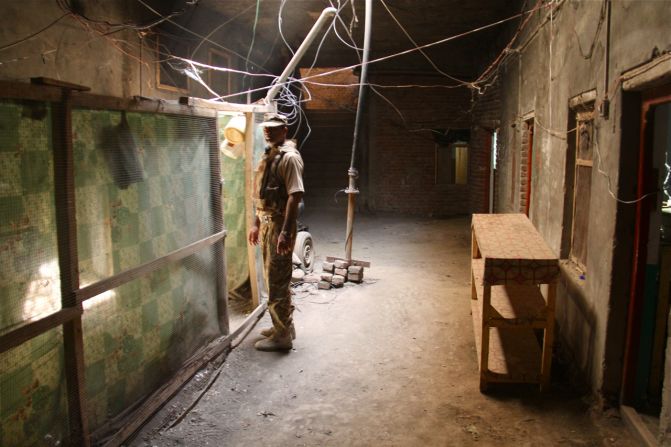

We’re led down a series of steep steps inside the compound, and we find ourselves in a cold, labyrinth of tunnels, with only the dim light from our torches to guide us. Bajwa tells us the tunnels “go on for at least two kilometers.” It’s a formidable operating base for militants.

The drive to the town proper is surreal: vintage film music plays as the soldiers accompanying us discuss the Germany-Brazil World Cup match the previous night. Outside our windows, we see troops searching blast-damaged and hollowed-out buildings. We’re told not to stray from the group since the area has not been completely cleared of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) – the signature bomb of militants in the region.

According to Maj. General Khan, at least 23 tons of IED-making equipment has been recovered from Miranshah.

In the courtyard of a house in the battered remains of the town’s bazaar, guns and ammunition have been displayed in abstract designs, bullets placed in macabre symmetry. Military officials tell us that this was the compound used by the East Turkestan Islamic Movement – a murky terror group blamed for attacks in other countries in the wider region such as China. We’re shown the in-house dental clinic that they had established for themselves. Alleged terrorists get toothaches, too, it would seem.

A mosque provides the front for another underground hideout; a series of steps lead up to a bookshelf that opens up like a door into a secret passageway that we’re told was used as an escape route.

It seems that no one was captured. Maj. General Khan says leaders of other groups such as the Pakistan Taliban fled into Afghanistan before the ground operation began. “They now manage things from across the border,” he says.

Military sources say over 400 militants have been killed in this operation, but information about which groups they are affiliated with is vague. Meanwhile, the number of internally displaced people from North Waziristan has now reached over 876,000, according to figures released by the FATA Disaster Management Authority, Pakistan’s federal government organization that administers the Federally Administered Tribal Areas.

Despite the access, details about the captured militants seem opaque. As we’re leaving North Waziristan, we find that a new militant group called Lashkar-e-Saif has declared its existence, claiming that the regions of “Spinwam, Dosalli, Razmak, Dattakheil, Shawal, Shava and other parts of Waziristan are under the full control of Taliban while security forces are only controlling Mirali Bazaar and Miranshah Bazaar.”

The military denies the existence of any such group. “We will never let militants return to North Waziristan,” Khan tells the press in this valley in the foothills of the Hindu Kush Mountains. Yet the very next day, Abidullah Abid, the spokesperson of the shadowy Lashkar-e-Saif claims they “will welcome security forces with bullets in Waziristan.”

This month of alleged gains by the Pakistani Army, it would seem is only the beginning for operation Zarb-e-Azb.

Journalist Saleem Mehsud contributed to this report from Islamabad.