Story highlights

- Belinda Davis: World War I changed women across globe in ways that affect us today

- She says they took up "men's work," supported home front and raised kids in privation

- She says male society struggled with how to acknowledge women after war

- Davis: Family tensions returned with soldiers, still women got vote in many nations

Some 100 years ago, a woman in Pittsburgh or St. Denis in France or Petrograd, Russia, might have awakened at dawn, while her young children slept, to prepare for her first shift at a nearby munitions factory. Her husband, off fighting in World War I, had left her to test the limits of her own physical ability, as she provided food, shelter, warmth for her family, sometimes confronting great physical danger at work -- perhaps, for example, hanging suspended to load powerful explosives into the shells that other women had produced.

When her work day was done, she went looking for food to buy, often standing in line for hours for scarce basic goods, scrounged for hard-to-come-by fuel to feed the furnace and cooked dinner. She washed the children, put them to bed, cleaned up and wrote a letter to her husband, keeping her worry off the page, before sleeping a few hours. And then she got up and did it again.

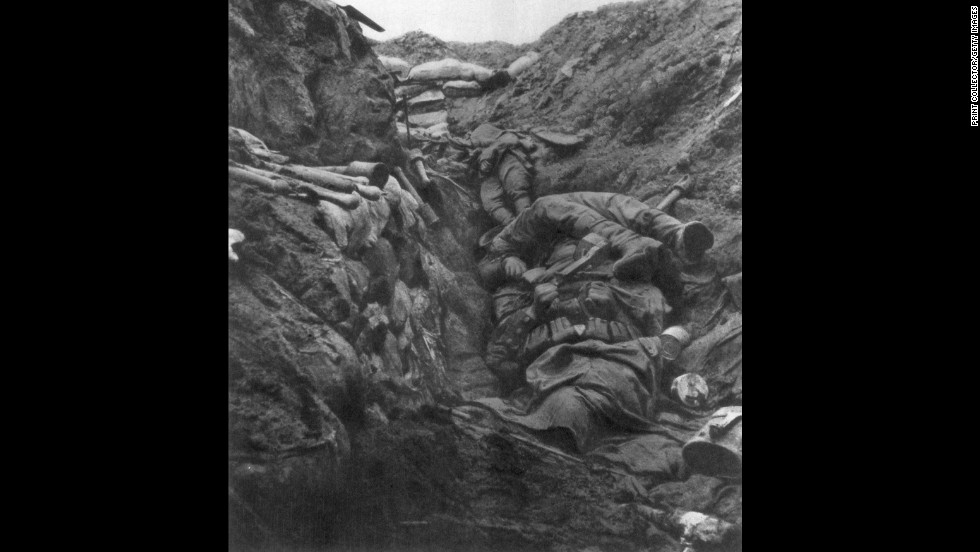

A century ago, as nations and empires began mobilizing to send 65 million men to war, millions of women across the globe moved to fill in the holes created in civilian society. From Britain to Bosnia to Baghdad, across the United States and Europe and India and Africa, women would become single heads of household in unprecedented numbers.

They would serve directly on the battlefields as nurses and ambulance drivers and cooks. Yet they also had to keep their nations' home fronts running, moving into "men's" jobs, from smelting iron, to driving streetcars, to plowing fields -- as well as working to administer new public and private organizations in support of the war.

The war changed life for women, and it changed the women themselves. When men returned from war, they inevitably tried to reassert their dominance in family and society. But their own broken conditions and circumstances at home challenged these attempts.

Women once again had to navigate a tricky terrain laid by men. Yet women had displayed to the world and to themselves their competence in "total war." Indeed, the war created a lasting legacy for women, marked by new political rights in many countries -- and marked also by widespread and enduring anxiety over rising feminine power.

In 1914, women were not new to the paid workforce. Individual industrial jobs were often considered as specifically for women or for men; entire industries, such as textiles, were "women's industries," while men dominated in metal forges and machine factories. While wealthier women continued to shun paid work, by the turn of the century, lower-middle-class women had begun moving heavily into positions as clerks and secretaries, and women remained central to farming labor.

But with the declaration of war, economic shifts and official pressure pushed them increasingly into war production and into "men's" jobs (even as, in France, authorities contradicted themselves and confused women by urging them rather to stay at home and have more babies). If only 170,000 women in Britain worked in metal factories on the eve of war, by its end in 1918, there were nearly 600,000.

In the United States and Great Britain, women confronted wartime shortages of food and housing.

As they took on jobs outside the home, many relied on irregular child care or were forced to leave children without care. While, as in other combatant countries, American women generally strove to "do their part" for the war effort and accepted official assignments of war-related work, from factory work to food distribution, some balked at having to "register" with authorities.

British propaganda posters declaring soldiers' dependence on female munitions workers gave women a sense that their labor contributions would be important and acknowledged.

Yet, even as women munitions workers faced heavy labor and harsh conditions -- along with danger such as in the Barnbow National Factory explosion of 1916 near Leeds, England, that killed 35 -- others condemned them for the relatively high wages they earned. It was a reflection of class tensions raised by the restructured wartime economy and women's role in it.

British authorities offered small "separation allowances," subsidies to soldiers' families based on the loss of income, and in turn assumed the right to check up on soldiers' wives, to make sure they were not drinking or sleeping with other men.

A woman who followed her own factory shift with dancing or a quick drink at the pub confronted public accusations of being a "flaunting flapper" or an "amateur girl" -- effectively a prostitute -- even as fellow male workers and soldiers on leave might proposition and harass her.

Some women felt new "freedom" during the war; others saw changing "moral standards" as the result of women who had seen their men "swallowed up in that ever-increasing wave of death ..."

In continental Europe, where the war was actually fought, conditions on the home front were even more challenging. Many women took on "men's work" to support the war effort and to ensure their families' survival but also found themselves subject to still more controlling government policies that came with "total war." Women living in captured territories suffered added misery, billeting and serving often abusive foreign soldiers.

In Italy, urban women were effectively drafted into agricultural labor. Women farmers were, however, little mollified by this motley work force intended to substitute for missing men and draught animals. In European cities, women often stood in line for hours for a chance to purchase spoiled potatoes; together with barefoot children, they tried to scavenge food and fuel from public parks, a practice that had become a full-time job in itself

In Germany, a 1916 policy reserved scarce food supplies only for women who worked in munitions factories, as officials announced that "the entire remaining civilian population, including women, were to be militarized through this plan." In the extraordinarily frigid winter of 1916-17, as schools shut down for lack of heat, the policy left few adults available to care for children.

By the end of hostilities, the war had transformed women's lives.

In many warring nations, acknowledging women's contributions became critical to warding off challenges to politicians' own power in the tumultuous postwar conditions, across Europe especially. Women won voting rights during hostilities or soon after in the United States, Canada and Great Britain; in the German Republic and the new Soviet republics; and in the new states of Austria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia.

Economic rights were a different matter.

Demobilizing soldiers and groups claiming to represent them pressured officials and factory owners alike to "make room" in the workforce for returning men by laying off all women although women frequently remained the only potential earners in their households. This was one manifestation of powerful and contentious culture wars over the desirability and even possibility of returning to some halcyon past -- one that, like today, was in part imagined.

Battles ensued across European and North American societies over how to otherwise recognize women's work during the war.

Should newly impoverished women receive government assistance on the basis of their wartime contributions or only as dependents of wounded or fallen soldiers -- or perhaps not at all?

In Britain, authorities shunned the arguments of women's groups and deferred rather to claims of the need to put men back in their "proper" role of economic power, by retaining the wartime notion of benefits deriving only through the husband.

In Germany and Russia, conversely, women were now in principle to have equal status, though the practice did not always follow the principle. The divided attitudes about the value of female work that informed these debates lingers today.

The flood of some 50,000,000 men back home at war's end in 1918 and 1919 also brought new tensions into family life. Returning soldiers imagined home as a refuge of normality after the nightmare of war. Yet men's physical and psychological injuries often precluded any return to their prewar existences, as did the social and economic upheaval of these years.

What was "normal" had of course changed for the women left behind. With their new roles and autonomy, they were often blamed for this world turned upside down. Such gender conflicts lasted through the 20th century and beyond, like many other legacies of World War I.