Editor’s Note: This is an excerpt from John Blake’s 2004 book “Children of the Movement” about James Earl Chaney, one of three civil rights workers killed in Mississippi 50 years ago this month. The story contains language that some people may find objectionable.

Story highlights

James Earl Chaney's siblings forced to flee home after his murder

Brother of slain activist says he hated white people

No one has ever been convicted in the murder of the civil rights workers

Chaney's daughter talks about dad she never knew

Ben Chaney slumped to the ground and covered his eyes to cry.

As a cluster of photographers circled him to snap his picture, the 12-year-old began to cry so hard that his thin body shuddered. People walked up to him to offer comfort, but he shooed them away. He finally rested his head on the right shoulder of his mother, Fannie Lee.

That was the first time most people would see Ben, the younger brother of James Earl Chaney, one of three civil rights workers murdered in Mississippi during the summer of 1964.

He was then known as “Little Ben Chaney.” In the pictures news photographers took of him at his brother’s memorial service, his resemblance to his brother was uncanny: the same almond-shaped eyes, high forehead and oval-shaped lips.

The last time Ben saw his brother alive was on a Sunday morning. James Earl Chaney, often called J.E., had stopped by with his friend and colleague, Michael “Mickey” Schwerner, for some homemade biscuits. Both were going to investigate a church burning and Ben wanted to go.

“No,” James Earl Chaney told his little brother. “We’ll be back later.”

Ben sat on his front porch that afternoon and waited for his brother to return. He waited into the evening. He waited so long that his mother finally ordered him to bed.

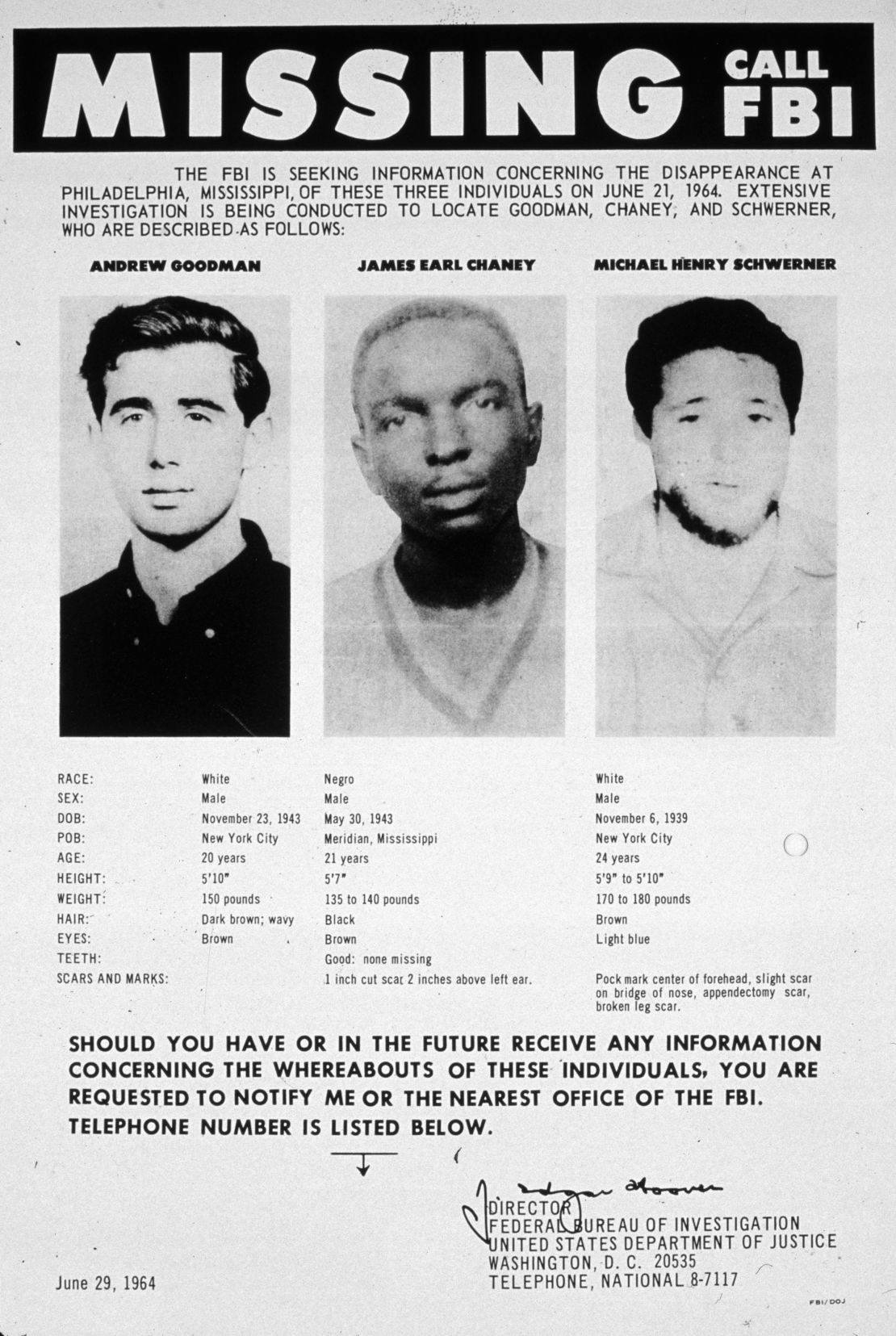

He would wait 44 more days before he discovered what had happened to his older brother. James Earl Chaney had been ambushed and murdered along with Schwerner and another civil rights volunteer, Andrew Goodman.

The murders became international news. Photos of “Little Ben Chaney,” shattered by grief at his brother’s memorial service, would make their way across the world.

But few people know what happened afterward to the grieving boy in the photos. Few know about the anger that followed Ben’s tears; the murder spree that claimed the lives of three white people; his 13 years in prison; and his eventual return to Mississippi to seek justice for his brother.

Few knew that when Ben collapsed into his mother’s arms and wept that morning, his pain was just beginning.

‘No one has been brought to justice’

Ben Chaney trudges through the snow in a wind-swept cemetery in Meridian, Mississippi, until he finally reaches the place. He stands on a desolate hilltop before a marble headstone printed with the name “James Earl Chaney.”

At the top of the headstone is a small picture of the deceased. But as Ben leans forward to look at the picture, his eyes narrow: two bullet holes pierce his brother’s image.

Ben traces the bullet holes with his right index finger. “This is the fourth or fifth time the grave has been desecrated,” he says. “Before, there were attempts to open up the vault to get to the coffin.”

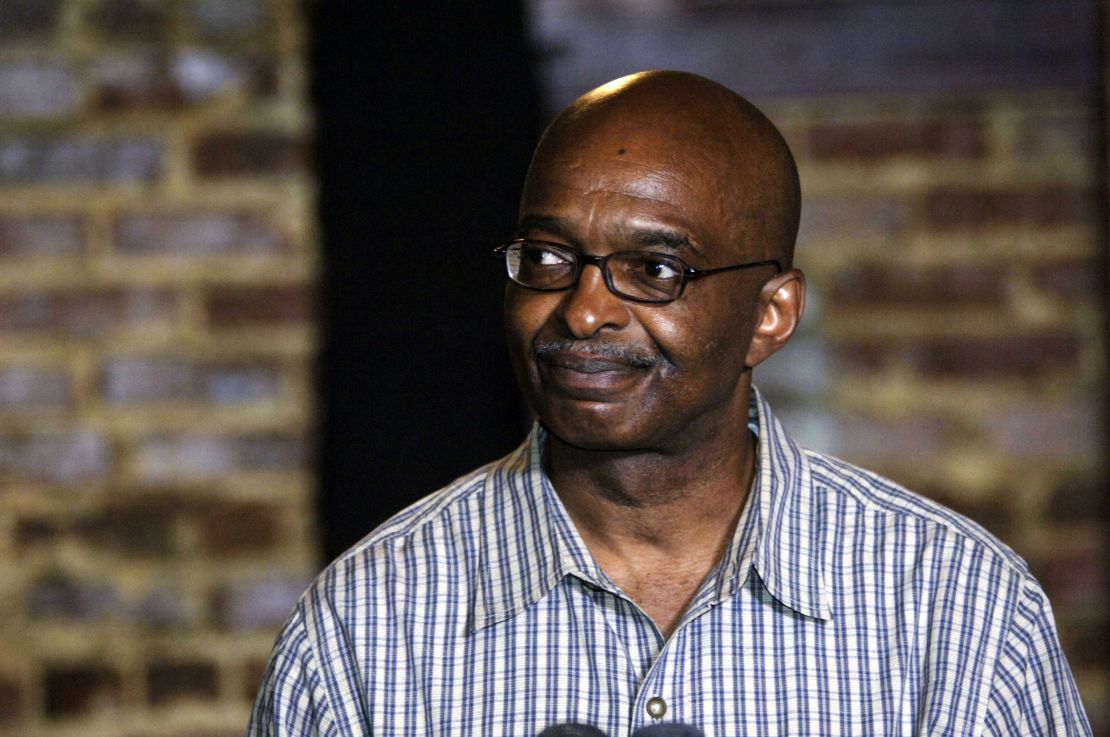

This is the first time I’ve met Ben. I’ve been assigned by a newspaper to meet him in Mississippi to talk about his brother. But he acts nothing like the sensitive 12-year-old who allowed the entire world to witness his grief. The 50-year-old man who stands before me is stoic, wary; his face betrays no emotion as he looks at his brother’s bullet-pocked headstone.

Why I’m tired of hearing about ‘that’ civil rights movement

Perhaps Ben needs all the emotional reserve he can get. For the past 13 years, he has spent much of his time traveling back to Mississippi to campaign for the retrial of the men accused in his brother’s murder. He also still has family in Mississippi – James Earl’s daughter, born a week after his murder.

When he’s not in Mississippi, Ben is a paralegal in New York. He’s experienced almost every angle of the legal system imaginable. He’s seen gloating Southern lawmen escape conviction in his brother’s death. His experiences with the legal system haven’t been good, but Ben is now trying to use the system to avenge his brother. He established the James Earl Chaney Foundation to preserve his brother’s memory, but he wants more.

Ben wants the men responsible for his brother’s death to be charged with murder. But he is running out of time.

Nineteen men were eventually arrested in the deaths of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner. Two of them were Mississippi lawmen: Sheriff Lawrence Rainey and Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price.

A Ku Klux Klan member confessed to FBI agents that he had witnessed the murders. He claimed that Price had arrested and released the three civil rights workers that night, knowing that a mob was waiting to ambush them on a rural road. But despite this and another confession, no Southern jury would ever convict anyone for the actual murder of Chaney or his colleagues.

In 1967 prosecutors managed to convict seven of the men for conspiring to deny the civil rights of Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman. None served more than 10 years. Some of those originally arrested, including Lawrence Rainey and Cecil Price, have died – Price fell from a cherry picker and Rainey died of throat cancer.

Ben believes that the state of Mississippi is hoping that the rest of the men will die so it won’t have to endure the ugly publicity of a new murder trial. He has personally reviewed the 2,900 pages of transcripts from the trial and even the autopsy photographs (he says his brother was beaten so badly before he was shot to death that it looked as if he had been in an airplane crash).

When he talks about his brother’s murder, Ben never brings up the possibility of forgiving the men who were arrested in his brother’s death. He says about 12 of them are still alive. Though they are old, he wants them tried again.

I ask him if he’s still angry after all these years. “I don’t know if I’m angry at them as individuals or as a group,” he says. “But I know that I’m angry over the fact that my brother is dead and no one has been brought to justice for his death.”

He has no interest in trying to discern the mindset of the men who killed his brother. He doubts if any of them experienced any guilt or regret during the years that have followed. “They feel the way they felt back in the 1960s,” he says. “They felt justified in what they were doing, and they still feel justified.”

Who was James Earl Chaney

Ben says his brother had no illusions about the men he was going against. He knew they would kill. But he persisted because there was this tremendous frustration building up among blacks in Mississippi by the early 1960s. “A lot of young African-American males in their teens and early 20s were looking for an opportunity to do something. When the opportunity came, a lot of them didn’t do anything, but a few did.”

James Earl Chaney didn’t wait long to plunge into the movement. A native of Meridian, he was once suspended from high school for wearing an NAACP badge. In 1963 he began working in the Meridian office of the Congress on Racial Equality, or CORE.

In the summer of 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer began. Young black civil rights workers in groups such as Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC, and CORE invited hundreds of white college students to come to Mississippi to help them register black voters. James Earl Chaney joined in.

Ben says history books and photos don’t do justice to his brother’s personality. The infamous poster circulated after the three civil rights workers were missing shows Chaney staring at the camera with a stoic, almost glazed, look on his face. But Ben says that his brother was a practical joker who liked to gather with his friends on the corner to sing Motown. He was asthmatic, but he managed to become the captain of his high school football and track teams. As he talks about his brother, Ben’s voice softens and his sense of humor bubbles to the surface. He still has his Southern accent.

Retracing a summer of terror – and freedom

Ben also has vivid memories of Schwerner, his brother’s murdered colleague. Schwerner had become a family friend through frequent visits. He was a chubby guy who loved baseball and nicknamed James “the bear” and Ben “the cub.” “The one thing I remember about Schwerner is that if you were in a room with him and he was talking and you didn’t know he was white, you would swear he was black,” Ben says.

Ben rode often with his older brother and Schwerner. It was fun, and he felt safe with his brother. They took him to demonstrations and Ben was even arrested twice. But his brother sensed that people were out to get him. “I think he was aware of the danger,” Ben says. “He had been out many other times before. He had driven at high speeds with no lights on, running from Cecil Price on back dirt roads. He knew what would happen if they got caught.”

When searchers eventually found his brother’s body buried in an earthen dam, Ben says he still refused to accept that his brother was dead. Then it hit him at the memorial service and all his grief came pouring out. “It wasn’t until early that day at the burial that I realized that, hey, this was final,” he says. “That’s when death became real to me.”

Then Ben began to receive other reminders that life was fragile. His family started receiving death threats over the phone. Their house became the object of random gunshots and firebombing. Some people weren’t satisfied that his brother was dead.

Finally Fannie Lee Chaney moved Ben and her three daughters to New York for their safety. Carolyn Goodman, the mother of Andrew Goodman, helped set the Chaney family up.

Goodman designated Ben as the first recipient of the Andrew Goodman Memorial Scholarship at the Walden School, an alternative private school where Goodman had once been a student. Ben was one of 25 black students in a student body of about 800. He was living in a big city for the first time. “It was like going to a foreign land,” he says.

But Ben never found his footing at Walden. He stayed there for five years but admitted he was an indifferent student. He would often skip school to seek his education in Harlem. “When I first went to Harlem, it was like heaven,” he says. “Black people were in control. The streets were clean. The music, poetry readings – Harlem, brother, was it.”

It was the late 1960s and black nationalist movements were seizing the imagination of young black people. Nonviolence seemed naive to them. Groups such as the Black Panthers talked about black power and using violence if necessary to defend their communities.

The message resonated with Ben, who was now a young man. “There was a period where I felt like I hated mankind,” he says. “I wanted to vent my hatred and my anger on white folks. To me, they were the main perpetrators for evil in the world.”

Ben became an activist like his brother. But it was different now: no nonviolent struggle. In late 1969, he and other activists took over a YWCA because it refused to install a Black Panther Party free breakfast program for children. He even organized one demonstration in New York that ended in a riot. He spoke around Harlem about the need for black people to train themselves in self-defense. Some people, though, questioned his black revolutionary credentials because he had been educated at a white school.

James Sullivan, another black high school student, met Ben during that time. Now a computer consultant in New York, Sullivan chuckles at the figure Ben cut when he started going around New York in his dashiki and sandals to tell black students to get organized. “He was a string bean, a bowlegged country bumpkin. He walked like he just got off a horse. He had that real, slow, Southern demeanor, definitely not New York.”

But Ben never talked about his brother’s murder to his friends. Sullivan says he only found out about it through others. When Sullivan brought it up, Ben didn’t elaborate. “It took us so long to realize who he was. There was never any celebrity about it. It was a fact of life for him.”

Despite his brother’s death, Ben didn’t seem to be driven by rage. “I never saw him yell or raise his voice,” Sullivan says. “He had this under-the-surface intensity. It was a smoldering intensity. It was like, we need to get things done.”

Ben says he didn’t become an activist just to avenge his brother’s death. Like many people, he thought a black revolution was imminent and he wanted to participate.

He got his chance and paid dearly for it.

A fateful decision

In April 1970, one of Ben’s friends asked him to accompany him while he visited a relative in Florida. On the way there, the man told Ben the trip’s true purpose: They would be picking up a shipment of guns in Florida to transport them to a Black Liberation Army unit in Ohio.

What happened next sent Ben to prison. Four white people were shot to death and two wounded during a murder spree that crossed Florida, North and South Carolina. At the age of 18, Ben was sentenced to life in prison for the murder of a white insurance salesman and two college students (he was acquitted in the murder of the fourth victim).

Ben maintains that the charge was not justified. “I never killed anyone,” he says calmly. “I was charged and convicted primarily because I would not tell after the acts were committed – I didn’t know the acts were going to be committed ahead of time. I did not go and tell the cops that this person had killed someone.”

Ben spent the prime of his life – 13 years – in prison. While there, he discovered that his last name both helped and hurt him.

Black prisoners respected and protected him because of his brother’s death. They knew he was coming before he actually arrived in prison. But prison officials tried to break him psychologically because of his name. He says he spent two years in solitary confinement because he questioned a white correctional officer about an order to cut his hair.

Prison, he says, transformed him. He got his associate’s degree in prison and later got his bachelor’s degree from John Jay College. He was a clerk in the prison library where he consumed books such as Malcolm X’s autobiography, George Orwell’s “Animal Farm” and various biographies.

Most of all, prison taught him patience, he says. “You spend a lot of time in line waiting. You gotta stand up in the morning and line up for the count. You gotta line up to go to breakfast, lunch and dinner. You gotta line up and wait for mail. You gotta line up to do anything.”

Ben’s name helped him win support on the outside. His mother, declaring that she would not lose another son, organized a letter-writing campaign to the parole board. The famous attorney William Kunstler filed his case with the Supreme Court, which refused to hear it.

In 1983 former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark finally interceded and persuaded the Florida parole board to release Ben. When he was released, Ben immediately flew to New York, where he remains today.

Sullivan says Ben still has a sense of mission. His office, where Ben frequently works well into the evening, is filled with books and articles on black America and the prison system. “Even to this day, I get calls from him about ideas he wants to try out. If I don’t move fast enough, he’s already moved on. I don’t think he can sit still. He has to be constantly doing something.”

Despite their lifetime friendship, Sullivan says they have never talked about Ben’s slain brother or his time in prison. “I guess it’s a thing guys just don’t talk about.”

James Earl Chaney’s daughter speaks

But Ben keeps close to Mississippi. In 1989 he established the James Earl Chaney Foundation to stop vandalism of his brother’s grave. Four years later, he returned to Mississippi to help in an investigation into the suspicious deaths of several young black men found dead in Mississippi jail cells. He has another reason for going back: His brother’s daughter, now 38, lives in Meridian. Angela Lewis, a nurse, has four kids and is married to a police officer.

Angela was born out of wedlock, a week after her father was murdered. She says she didn’t know how her father died until she was about 13 years old. Before and since that time, her mother has never talked about her father.

Nor does her grandmother talk about her father’s death much. “My grandmother is still hurt,” she says. “If you speak with her, you would sense that my father’s death just happened yesterday.”

When she discovered how her father died, Angela says she didn’t experience any anger or deep sadness. She couldn’t miss someone she never knew. “My reading about him today is like reading about a stranger.”

She remembers reading about her father in high school history class. But she would never say a word about who she was. She didn’t want the attention. It was only when she became a mother that she really missed her father. “I didn’t realize what I missed until I saw my daughter with her daddy,” she says. “Just to hear her calling him Dad and know how he’s always there for her – that’s the only time I had that sense of longing,”

A devout Christian who sings in her church choir, Angela talks easily about her loss. She says she even occasionally saw the man accused of murdering her father, former Sheriff Lawrence Rainey. He was a security guard at a mall near her home.

She says she never was tempted to say anything to him. “I don’t think he ever changed,” she says. “I don’t think a conversation would have changed him. From what I heard, he still referred to us as niggers.”

Angela says she doesn’t hate the men who murdered her father. She thinks somehow they will pay – in this life or the one to come. “What happened to my dad was because of hate,” she says. “For me to live in hate would be to carry on the very thing that took him out of the world.”

Ben says he has changed, too. He no longer hates white people. He was baptized eight years ago and is the father of a 16-year-old girl, Amelia. “I’m an old man now,” he says ruefully. “The time for violence is pretty much past. It’s not a viable tool. Black people aren’t prepared for the consequences. We’re too entrenched in this system. We have to look for ways to make the system work for us.”

That system, however, still has not worked for Ben.

He’s no longer the 12-year-old boy sitting on the front porch waiting for his big brother. He’s a man now. But four decades after his older brother was beaten and shot to death on a deserted Mississippi road, no one has been convicted for his murder.

Ben is still waiting.

A year after this story was published, the state of Mississippi charged Edgar Ray Killen with the murder of the three civil rights workers. A jury found him guilty of three counts of manslaughter. He was sentenced to 60 years in prison, where he remains. Not one person, however, has ever been successfully convicted of murder in the deaths of the three civil rights workers.