Story highlights

Crew may have been in an "unresponsive" state, Australian authorities say

Plane was likely on autopilot when it flew into the Indian Ocean, officials say

The next phase of the search will move to an area farther south in the Indian Ocean

The area is the "most likely place where the aircraft is resting," an Australian official says

Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 likely flew into the southern Indian Ocean on autopilot with an unresponsive crew, Australian authorities said Thursday, divulging new details about what they believe happened during the missing plane’s final hours.

The information emerged as officials announced a southward shift, as expected, in the underwater search for the Boeing 777, which disappeared March 8 with 239 people on board.

Searchers have found no trace of the jetliner or its passengers, making the case probably the biggest mystery in aviation history and leaving the families of those on board bereft of answers.

The Australian officials said they believe the plane was on autopilot throughout its journey over the Indian Ocean until it ran out of fuel. They cited the straight track on which the aircraft flew, according to electronic “handshakes” it periodically exchanged with satellites.

“It is highly, highly likely that the aircraft was on autopilot, otherwise it could not have followed the orderly path that has been identified through the satellite sightings,” Australian Deputy Prime Minister Warren Truss told reporters in Canberra.

Unresponsive crew?

In a report explaining the change in search area, Australian authorities suggested that Flight 370’s crew may have been in an “unresponsive” state, possibly caused by a lack of oxygen.

That scenario “appeared to best fit the available evidence for the final period of MH370’s flight,” the report said, citing previous air accidents in which crews had been rendered unresponsive by a lack of oxygen, also known as hypoxia.

But it cautioned that the assumption was “made for the purposes of defining a search area and there is no suggestion that the investigation authority will make similar assumptions.”

The Australian officials declined to talk about the causes behind Flight 370’s errant flight path, saying those are questions for the Malaysian authorities in charge of the overall investigation. And they said they weren’t sure exactly when the autopilot had been turned on.

‘Most likely place’

Their disclosure that a computer rather than a human was most likely steering the plane during its final hours adds a little more detail to the largely obscured picture of what took place that March night.

But the key questions of why the passenger jet flew dramatically off its intended route – from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, to Beijing – and where exactly it ended up remain unanswered.

The next phase of the underwater search aims to resolve at least one of those issues.

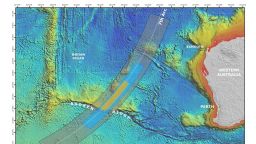

Truss said an international team of experts had chosen the 60,000-square-kilometer zone, an area roughly the size of West Virginia, after going over all the available data.

“This site is the best available and most likely place where the aircraft is resting,” he said.

He warned, though, that the operation to comb the sea floor in the area, which has never been fully mapped, would be “very challenging and complex.”

“We could be fortunate and find it in the first hour, or the first day,” he said. “But it could take another twelve months.”

Biggest search in history

The hunt for the plane has already become “biggest search operation in history, covering 4.5 million square kilometers of ocean surface,” Truss said.

During the early phase of the search, aircraft and ships scoured vast stretches of the surface of the southern Indian Ocean but found no debris from Flight 370.

Pings initially thought to be from the missing plane’s flight recorders led to a concentrated underwater search that turned up nothing.

Last week, a group of independent experts – using satellite data publicly released in May – said it thought the missing aircraft was hundreds of miles southwest of the previous underwater search site.

Doubts among families

“It is encouraging that the Australian leadership has taken a very methodical and rigorous approach to redefining the search area, but is it still different than some of the other outside experts had defined,” said Sarah Bajc, whose partner, Philip Wood, was on board the missing plane.

She said she couldn’t reconcile the differences between the analyses.

“We don’t trust that the officials are being forthright with the information,” she said.

The next underwater search will be broadly in an area where planes and vessels had already looked for debris on the surface of the water, Truss said. It’s roughly 1,800 kilometers off the coast of Western Australia.

Two ships have already started mapping the ocean floor of the area, a process that will take about three months.

The underwater search, which will rely on the ships’ maps, is expected to begin in August. It will be led by a private contractor that Australian authorities will appoint.

Malaysia will contribute equipment to the search effort, including vessels and towed sonar systems, Truss said.

For families of the missing, a hole in the clouds, an empty space on earth