Story highlights

CNN team reports that Slovyansk appears half-deserted, after residents flee fighting

Eastern Ukrainian city has been held by pro-Russian separatists for two months

Slovyansk is under persistent shelling and mortar fire from Ukrainian forces

Citizens appear weary of fighting, desperate for end to constant threat of bombardment

We were on a rough track surrounded by fields of wheat and barley when the little blue Lada came into sight. The car lurched towards us, kicking up a trail of white dust. Both vehicles stopped. Within 20 miles of Slovyansk, drivers routinely quiz each other for information on the road ahead – the risks and roadblocks.

And then the car, barely the size of a Mini and at least 20 years old, disgorged its occupants: no fewer than eight people, three generations of the Goma family.

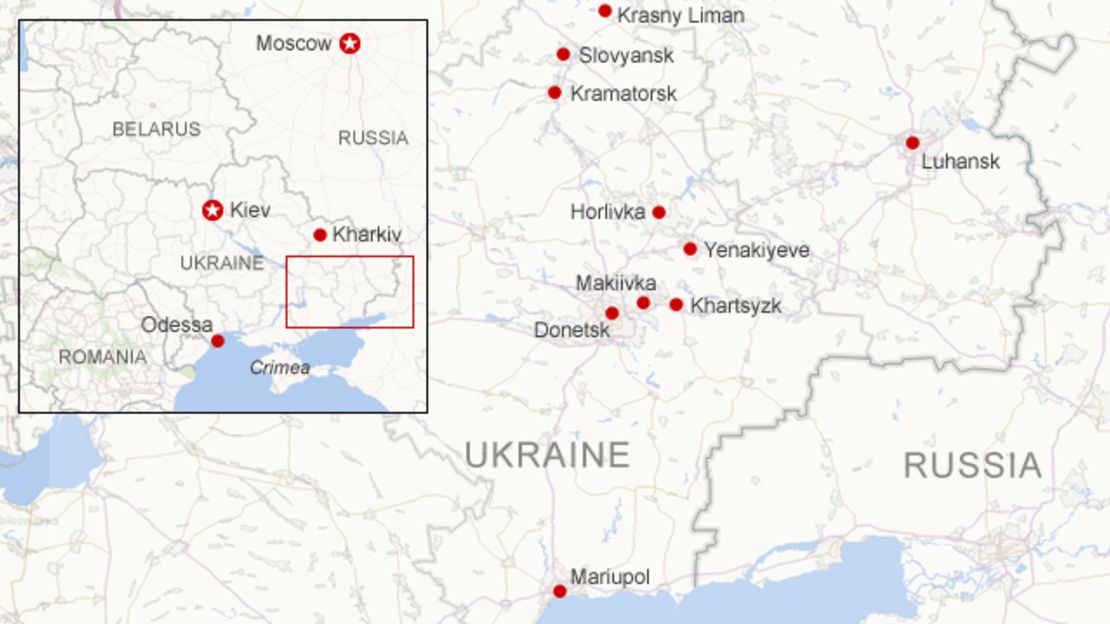

They had fled the shelling in Slovyansk, a city in eastern Ukraine held for two months by pro-Russian separatists and now under persistent shelling and mortar fire from Ukrainian forces. But after a week sleeping in tents in a forest, battered by thunderstorms, they just wanted to go home – to a city without electricity, gas or running water.

We followed them along rutted tracks and lanes on a twisting route into the city, probably the only way in or out. The Ukrainian army has blocked the main roads around Slovyansk, although President Petro Poroshenko has promised to create ‘green corridors’ to help civilians escape the fighting. Waved through a couple of separatist checkpoints, they finally made it.

Compared to a month ago, Slovyansk seemed half-empty, the city’s remaining residents looking drawn and frightened.

The thud of artillery and chatter of gunfire echoed around apartment blocks. Jagged shards of glass lay everywhere, the remnants of windows blown out by mortar fire or shells. The roof of a gas station hung precariously, twisted by what appeared to have been a direct hit. There were a few charred vehicles, some small craters.

‘No electricity, no water’

When the Gomas arrived at a rundown apartment block, the neighbors were surprised to see them back. Who would return to this? They asked. But Tatiana Goma was just relieved her home was still there.

“Of course I’m worried to be here but home is home. There is no electricity and no water but at least it’s better than living in tents in the woods,” she told us after unpacking her few belongings.

“We had nowhere to stay,” Tatiana said – and people elsewhere were reluctant or unable to provide shelter. She knew of only four friends who had left. They had gone to Kharkiv, a city to the north, but had not been welcome.

Katya Goma said she was giving tranquilizers to her children – age ten and two – to calm them down. But they were already beginning to recognize the difference between various weapons.

An old man wandered past. Was there any water here? He asked. There wasn’t. Try the fountains, someone suggested. Others said they were using buckets to collect water from lakes on the outskirts of town.

Pro-Russian separatists, in various uniforms but all armed, wandered the deserted squares or careered through the streets on scooters, assault weapons slung over their shoulders, weaving past downed power cables. But there were fewer of them than before. Most, it seemed, were on the outskirts of town in defensive positions.

The office of the self-declared mayor, Vyacheslav Ponomarev, had lost its revolutionary brio. In fact Ponomarev was nowhere to be found.

A statement attributed to the military commander of the separatists in the Donetsk People’s republic, Igor Strelkov, and carried by the Russian news agency ITAR-TASS said: “The so-called people’s mayor Ponomarev was removed from office for activities which are incompatible with the objectives of the civil administration.”

Call for negotiations

Following the killing of an aide to Denis Pushilin, the self-declared mayor of Donetsk, in the city at the weekend, there is growing speculation here of dissent among the separatists’ ranks – though its leadership accused Kiev of being behind the murder.

Alexei, a man in his fifties got off his bicycle to talk to us. This had gone on too long, he said. “They need to negotiate, they should somehow settle this. Or the Ukrainian government should say: ‘That’s it. We’re bombing. Run away.’”

The support among some townspeople for the separatist groups that seized the town’s administrative and security buildings early in April seemed to have given way to a weariness, a yearning for an end to the uncertainty and the constant threat of bombardment.

No-one could be sure who had fired the mortar that had wrecked an apartment building and sprayed the wall of a school with shrapnel. Maybe it was poor targeting by separatists who had been using the cover of a church to fire at Ukrainian positions – or equally poor targeting by the army.

Those who have basements spend much of the evening sheltering; they said the worst of the fire comes after 8pm.

Others have no basement to flee into. One man said that when the bombing started he and his family would hide in the corridor of their house, away from the windows, for hours on end. They couldn’t go into the kitchen or bathroom.

Thunder, rocket fire

As we reached the bus station, a furious summer thunderstorm erupted. The potholes quickly filled with brown water, the thunder cracked – or was that another round of rocket fire from somewhere?

Galina Sergeyeva, a middle-aged woman with a look of resignation on her face was taking shelter, hoping against hope that she would be able to get home. She had nothing good to say about Poroshenko.

“We call him bloody Petro,” she said. “A lot of people have died but no-one is talking about it. They should pull the army back,” she said.

Katya, an elderly woman in a flowing blue dress and clutching two shopping bags sat on a bench nearby. She had braved the journey from a nearby village to Slovyansk to collect her pension. But the bank, she told us, had been destroyed. Now she had to get home. Suddenly, a puppy emerged from one of her shopping bags. She had found it and was taking it home.

As the downpour continued, the patter of rain occasionally interrupted by bursts of machine gun fire in the distance, she gave the puppy some milk – before traipsing away across the puddles in search of a ride home.

We found her at a roadblock an hour later, standing among bronzed separatists whose position was overlooked by Ukrainian heavy armor. The puppy was at her feet.

We made room for the pair of them and dropped them off at her home in a village just a few miles from Slovyansk – a picture of rural tranquility compared to the beleaguered city.

READ MORE: ‘It’s hell down there’ - battle for eastern Ukraine

READ MORE: Slovyansk burns as new President calls for peace