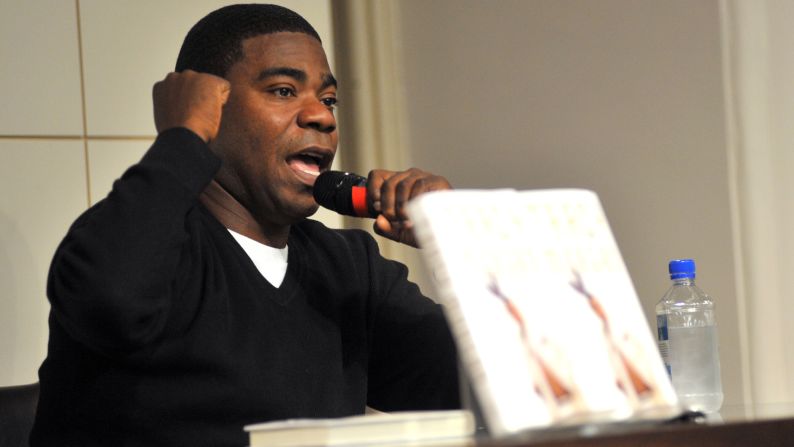

Editor’s Note: Danny Cevallos is a CNN legal analyst, criminal defense attorney and partner at Cevallos & Wong, practicing in Pennsylvania and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Follow him on Twitter @CevallosLaw. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

Danny Cevallos: Trucker in Tracy Morgan crash charged with death by auto, assault by auto

In N.J. vehicular homicide from reckless driving

He says state must show conscious disregard of risk

Cevallos: Assault charge defines culpability based on severity of injuries

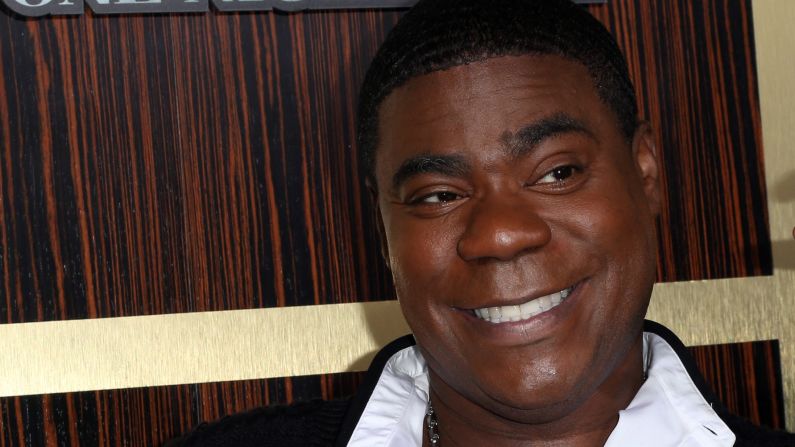

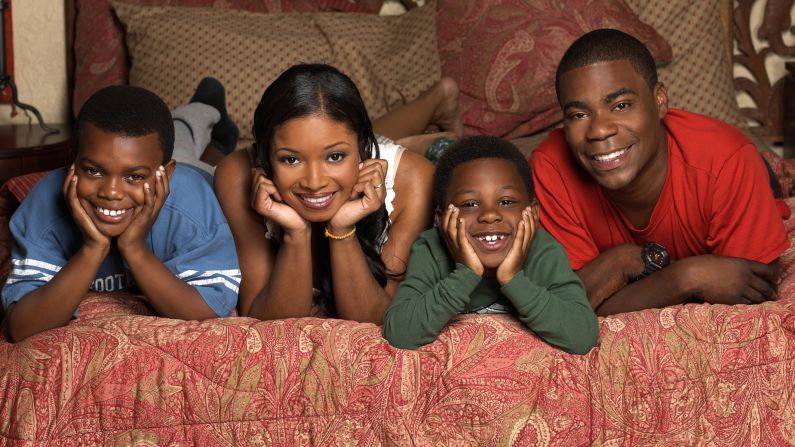

Truck driver Kevin Roper has been charged with death by auto and four counts of assault by auto in connection with the crash last weekend that killed comedian James McNair and injured comedian Tracy Morgan.

The question has arisen: Why was he charged with death by auto and aggravated assault before we even know how he was driving? In this sort of crash, what makes the difference between an accident and a crime?

The answers lie in the criminal code.

Homicide

Roper has been charged with “death by auto” in connection with the killing of James McNair. In New Jersey, homicide as a crime is divided into three different categories: murder, manslaughter and – in a category by itself – death by auto. Vehicular homicide is causing a death by driving a vehicle or vessel “recklessly.”

There are two elements hidden in that definition. First, causation: The defendant has to have caused the death. It must be shown that the defendant caused the crash, the crash caused the death, and that the victim’s death was foreseeable. The concept of recklessness, however, is a little more difficult to grasp. Recklessness and negligence are often spoken of together, but they are two very different points on a “mens rea” (state of mind) spectrum.

Criminal negligence is the least blameworthy state of mind. It’s an “objective” standard, which means that we simply ask if an ordinary, reasonable person would have done the same act – the act that created the risk in the first place. The prosecution doesn’t have to prove that the defendant actually knew better, just that he should have known better.

Recklessness is totally different. Both the negligent person and the reckless person create a risk of bodily injury, but the reckless person does so in conscious disregard of that risk. So, the state must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that this defendant’s driving created a substantial and unjustifiable risk of bodily injury. With recklessness, the state must also prove that the defendant consciously disregarded this risk, which was a gross deviation from what a reasonable person would have done.

So how on earth does a prosecutor get into a defendant’s brain to know what he was thinking at the moment of impact? The truth is that we never know for sure what a defendant actually thought – unless, of course, the defendant tells us what he thought.

Often defendants give statements or admissions to the police that can be introduced against them in court. While it’s true that hearsay (what the person told someone else) is supposed to be inadmissible, the admission of a criminal defendant is an exception to this rule. Of course, if a confession is obtained through compulsion or coercion, it is considered unreliable, and is inadmissible. But, as long as the state can prove conclusively that a confession was made voluntarily, it will be admissible.

But how often does a driver admit to police “I drove recklessly?” Not often. Therefore, the law also permits us to draw inferences about a person’s state of mind, based just on their conduct. In fact, certain behavior is specifically considered reckless by the law. And that’s where this defendant may find his words come back to haunt him – even if he never uttered the words “reckless” to the police.

New Jersey’s criminal code has this to say: “[p]roof that the defendant fell asleep while driving or was driving after having been without sleep for a period in excess of 24 consecutive hours may give rise to an inference that the defendant was driving recklessly.”

The easiest way to find out a driver was dozing off is if he admits it. Since the defendant in this crash was alone, only he would be able to tell police if he was asleep. Even an offhand comment to investigators about “drifting off” would have dire consequences, because it all but establishes a major part of the case against him.

The 24-hour alternative could be proved with circumstantial evidence, such as records, communications, or even witness testimony. Either way, the state would have the burden of proving sleep. If the defendant admits to dozing off, he’s saved the state the inconvenience of its burden. See why criminal defense attorneys are always begging clients to not try to talk their way out of trouble?

This kind of homicide is a second-degree offense, punishable by up to 10 years in state prison, and there is a presumption of incarceration. This means if he’s convicted, he’s probably going to prison.

Assault

Roper has also been charged with “assault by auto” in connection with the other injuries caused. Assault by auto also has the recklessness standard, but here the seriousness of injury also guides the degree of the crime charged. Assault by auto is a crime of the fourth degree if serious bodily injury results.

On the other hand, if only “bodily injury” results, it is only a disorderly persons offense. It’s interesting that criminal statutes define culpability in part by the injuries suffered, but in this case, the “seriousness” of the bodily injury – Tracy Morgan was left in critical condition, for example – is apparent, which is why the state has charged Roper with a fourth-degree offense. This is punishable by up to 18 months in state prison.

Ultimately, for both assault and death by auto, the prosecution must prove reckless behavior beyond a reasonable doubt. If Roper made statements or admissions to the police about falling asleep at the wheel, those statements could dramatically alter the course of the prosecution against him, potentially conceding a major part of the state’s case against him.