Editor’s Note: Simon Moya-Smith is a citizen of the Oglala Lakota Nation and a writer living in New York. He has a master’s degree from the Columbia University School of Journalism. He tweets @Simonmoyasmith.

Story highlights

Simon Moya-Smith: The death of original code talker Chester Nez is a significant cultural loss

Nez attended boarding schools that discouraged the use of his Navajo language

Author: Native American elders say when a language dies, so does the culture

Without the use of the Navajo language, the U.S. military could have lost a war, author says

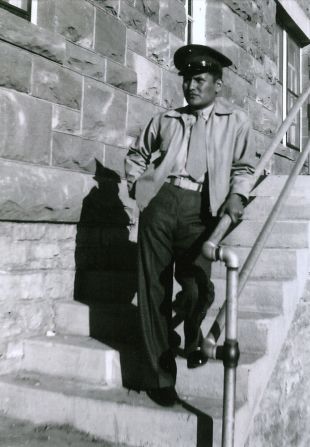

Chester Nez, the former Marine and last of the original 29 Navajo code talkers, passed away June 4 at age 93.

When an elder dies in Indian country – especially someone as revered and decorated as Nez, the World War II veteran – we, Native Americans, feel it, all of us, regardless of tribe or nation.

We are also reminded that, not long ago, in the 19th and 20th centuries, Native American culture, including our languages, was considered a threat to U.S. national security.

Then, the government worked in collusion with Christian institutions to stamp out Native American languages, including Navajo.

“A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one,” Capt. Richard Pratt famously read from a paper at an 1892 convention. “In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

Pratt was the founder of the Indian boarding schools, institutions charged with turning the “red Indian” into the “noble savage.”

Native Americans: We’re not your mascots

Chester Nez attended one of these schools as a child, and was punished when he spoke Navajo

One can’t help but think that, had it not been for the resilience of the Navajo people and their resistance to these early oppressive American policies, it’s quite possible that World War II could have ended differently.

Without the use of the Navajo language that was once discouraged by American policy, the U.S. military could have lost a distinct advantage over its enemy.

Nez’s death is a reminder that America’s strength lies in its diversity. Native Americans, who have not always been included in the American story, should be remembered and honored for their contributions.

Before the arrival of the Europeans, there were between 300 and 500 unique languages spoken throughout what is now the United States and Canada.

Today, there are fewer than 200, and that number will continue to decrease if North American indigenous language revitalization efforts aren’t considered paramount to the continuity of Native American communities by the United States.

Opinion: NFL may throw flag on N-word, but what about the ‘R-word’?

Recently,a neighbor and I were discussing Native American languages. He was curious why more Native American elders “don’t just pass on the language to the next generation.”

I told him that many of said elders still suffer from the trauma they experienced in the Christian boarding school system, and remembered what Ruby Left Hand Bull told me recently.

“They’d pierce your tongue if you spoke your language!” my elder recalled. “Or they’d make you stand in front of the classroom and they’d tell you to stick your tongue out and then they’d whip it with a wooden ruler, just for speaking our language.”

Ruby knew our Lakota language growing up, she said, and very well. But she has lost it, she said. She understands it, but it’s all but left her, courtesy of the boarding schools.

I told my neighbor, who said he was a third-generation Italian-American, that his people’s language could die in New York, but there is no threat that it will become an extinct language any time soon.

“There are more Italians speaking Italian every day right across the Atlantic,” I said. “You could board a plane or hop a ship today and travel to your home country and hear your people’s language reverberating off Italian walls. We, Native Americans, don’t share in that luxury. This is it. This is our home country. Our languages are invariably on the brink of extinction, especially since we are 1% of the population. So when a Native American language dies, it’s forever gone.”

Our elders tell us that when a language dies, so, too, does the culture.

But all is not lost.

There are various campaigns to revitalize Native American languages. The state of Colorado, for example, passed a law stating that Native Americans who speak their languagecan teach it to students for credit at secondary schools under the category “World Languages.”

Maybe one day all Native Americans will, again, be fluent speakers of their language – just like Chester Nez, the warrior.

Indeed, the world would be a richer place for it.

My hope is that when President Barack Obama visits with our Native American leaders this month at Standing Rock, North Dakota, he will be reminded of the significant contributions of Native American peoples like Chester Nez.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Simon Moya-Smith.