Story highlights

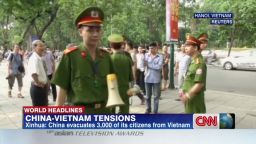

China and Vietnam at odds over a chain of largely uninhabited islands in the South China Sea

Recent oil drilling operations by China near the Paracel Islands, which they administer, have irked Hanoi

CNN traveled with Vietnamese coast guard to see how this conflict has become so volatile

Vietnam says Chinese vessels are being highly aggressive, often using water cannon

To be at the front line of a “cold war” is, these days, a rare thing – particularly when that front line is a remote chain of islands in the South China Sea, hundreds of kilometers from the nearest landfall.

The waters around the Paracel Islands, a largely unpopulated archipelago administered by China but claimed by Vietnam, have become the “battleground” in an increasingly volatile territorial dispute between the two communist neighbors.

Taking advantage of a rare opportunity to witness the spat up close, CNN traveled to the area with the Vietnamese Coast Guard.

Tensions between Beijing and Hanoi ratcheted up last month, when a Chinese state-owned company deployed an oil rig in waters off the Paracels. It was set up unilaterally, without any discussion between the two sides, much to the annoyance of the Vietnamese who view it as a Chinese incursion into their sovereign waters.

Since then, an increasing number of Chinese and Vietnamese ships – both government and private fishing boats – have crossed paths in the area with occasionally serious consequences – not least reports of Chinese vessels using water cannon and ramming fishing boats straying too close to the oil platform.

Entering the fray

Our trip out to this marine flashpoint didn’t start well. After days of prevarication over our departure date from the Vietnamese port of Da Nang, an official told us – the small contingent of foreign correspondents selected for this rare press trip – that while at sea we would confined below decks.

“We don’t want the Chinese to know we have journalists on board,” he explained. As expressions ranged from the defeated to the incredulous, this new piece of information was hastily qualified. “Don’t worry, there are plenty of windows that you can film through.”

We eventually did set off, hustled out to sea as the light faded over Da Nang, two and a half days later than planned. Crammed into a small supply boat heading out to the Paracel Islands, about 160 nautical miles (296 kilometers) from Vietnam’s central coast, it wasn’t long before the boat fell quiet and the 40 journalists – both local and international – took to their bunks.

The crew, despite their casual, day-to-day appearance – they only wear uniforms for official duties and, it turns out, camera appearances – were serious, and resolute in their roles – the first line of defense against what they see as Chinese aggression.

Toeing the party line

The Vietnamese refrain about these territorial waters is constant and unerring. Crew members explained to me that China is breaking the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, and that the vessels are engaged in illegal activities in waters that are part of Vietnam’s continental shelf.

Once away from Vietnam’s coast, we transferred to a bigger ship, Coast Guard 8003, one of the service’s most prominent vessels, and armed with 25 mm and 14.5 mm cannon – although I was told that they did not bring live ammunition on these patrols. Fears of being locked in below the waterline quickly faded as we were permitted on deck.

It is lonely out on the water, a vast expanse stretching hundreds of miles in each direction, and around a thousand meters beneath our hull. Topside, a lone seagull followed the ship as it began its regular patrol up and down a line adjacent to the oil rig, which eventually loomed large on the horizon.

The oil rig – identified as HD-981 – is omnipresent. It’s there in everyone’s minds, it’s the focus of much of the conversation on the boat, and it’s physically visible for most of our time at sea – though we keep our distance.

Despite our considerable distance from land, the horizon bristles with the silhouettes of dozens of ships, a mixture of Vietnamese and Chinese Coast Guard vessels and fishing fleets from both sides. The Vietnamese fishing boats are draped in red banners, which urge the Chinese to leave their territory.

Dangerous dance

For the most part, ships circle, warily keeping their distance, and posture at each other from afar. However, things can, and do, spill over. Hours before we arrive in the area, a Vietnamese fishing boat has been capsized, purportedly rammed by a Chinese vessel.

While the Chinese insist the Vietnamese side was at fault, the captain of the sunk vessel told me days later that he was sure the boat that hit them was a Chinese Coast Guard vessel disguised as a fishing boat – such is the level of suspicion and mistrust in this hotly-disputed body of water.

In charge of CG 8003, one of the service’s largest and most prominent vessels, Captain Nguyen Van Hung has around 50 men under his protection and a very visible role to play in this conflict with China. He says that there is no communication between his ship – or any other Vietnamese vessel – and the Chinese; no open radio channel, no way to prevent events from escalating dangerously.

Our Vietnamese hosts insist they are determined to resolve the matter peacefully and in full accordance with international law, but beyond the recorded warnings blasting out of loudspeakers into the heavy, humid sea air, it is not certain what their presence hopes to achieve.

Chinese attacks

China’s response is a little more robust, it would seem. Video taken by a CNN affiliate, among others, shows Chinese vessels attacking Vietnamese ships in the disputed area with water cannon and also ramming them.

A Vietnam Television (VTV) crew embedded with CNN aboard CG 8003 says the previous vessel they were aboard, a government fisheries surveillance ship, was itself rammed by the Chinese Coast Guard.

For its part, China abides by its territorial claims and blames the Vietnamese side for ratcheting tensions. “The drilling activities of this rig are within China’s territorial waters. The harassment by the Vietnamese side is in violation of China’s sovereign rights,” said Hua Chunying, spokesperson of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

For the media contingent, there is no direct experience of Chinese aggression as we sail up and down a furrow of the South China Sea, though from time to time we discover a Chinese Coast Guard vessel stalking us, gleaming white in the unceasing sun, but they never come closer than a couple of hundred meters.

We are, however, woken early one morning to see what the captain said was a Chinese coast guard vessel using water cannon on a Vietnamese fisheries surveillance vessel. At distance, the arc of the water looks graceful, but up close it is a vicious jet which can break windows, disrupt engines and cause electrical failure and even fires.

Saber-rattling

While Chinese ships keep their distance, they are intent on making their presence known. When the ships are close enough, we can see the deck-mounted guns have had their tarpaulins removed – a less than subtle signal perhaps. In any event, the sight of naked weaponry only dozens of meters away is unsettling.

The Chinese presence is also felt in the air. Towards the end of our embed aboard the ship, we see a surveillance plane – which journalists aboard the coast guard vessel are assured is Chinese – leisurely bank around our vessel time and time again, sometimes flying low and close enough for those on board to make out its markings with the naked eye. While there is no immediate threat from the aircraft, its intelligence-gathering is enough to make those on board jumpy.

For now, though, tensions remain largely under wraps. But for as long as both sides maintain their equally intransigent positions, shrilly trading blame and engaging in low-level incidents of maritime thuggery, signs of this feud diminishing, and ending up as a footnote in the history books, remain distant.

READ: How an oil rig sparked anti-China riots in Vietnam

READ: China, Vietnam, Philippines collide amid escalating tensions