Story highlights

NEW: Tuam archbishop says he will seek a "dignified re-interment" of children's remains

Remains reported found in County Galway are believed to date between 1925 and 1961

Irish Mail cited the efforts of a local historian to research burial sites of children

Pressure grows for investigation and accountability from government, Catholic Church

Outrage over the reported discovery of the bodies of almost 800 children at a former home for unmarried mothers run by nuns in Ireland prompted calls Wednesday for a full investigation.

The children whose remains have apparently been found in Tuam, in County Galway, are believed to have died between 1925 and 1961, according to local media reports.

The grim discovery was highlighted in a front-page report in the Irish Mail on Sunday, which cited the efforts of local historian Catherine Corless to research the burial sites of 796 children listed as having died at the home, which was run by the Sisters of Bon Secours.

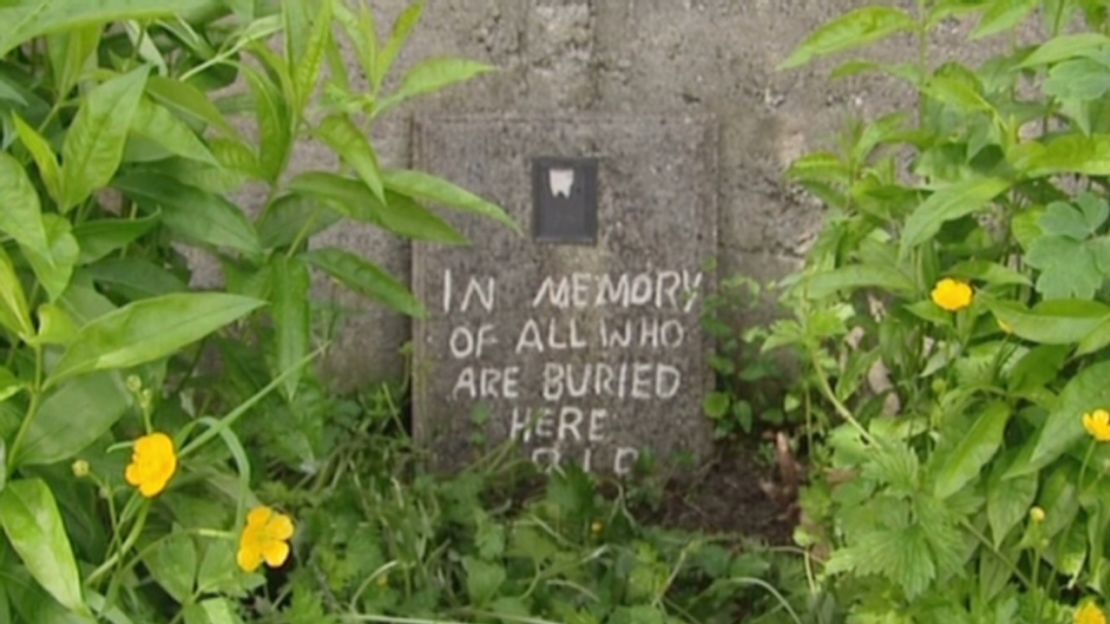

According to the newspaper, Corless believes their remains are all buried in the unmarked mass grave next to the place where the home once stood. Local children stumbled upon the grave in the 1970s, local media reported, but the site was never examined afterward.

The revelation has sparked calls for an investigation and renewed questions about the treatment of unmarried mothers and their children by the Catholic Church and institutions associated with it.

Sgt. Brian Whelan, in the press office of Garda, Ireland’s national police, told CNN there was nothing to suggest any impropriety and that police are not investigating the matter.

Whelan also disputed media reports that remains were found in a septic tank. The skeletal remains were found in a graveyard in the grounds of the home, he said.

Minister for Children and Youth Affairs Charlie Flanagan said in a statement Wednesday that “active consideration” is being given to how to address the details that have emerged about the burial of children who died in homes for unmarried mothers.

“Many of the revelations are deeply disturbing and a shocking reminder of a darker past in Ireland when our children were not cherished as they should have been,” he said.

Government departments are working together to establish the best course of action, said Flanagan.

‘Tip of the iceberg’

Opposition parties Sinn Fein and Fianna Fail urged a comprehensive government inquiry into the matter.

“The news that the remains of some 800 babies were found on convent grounds in Tuam has shocked citizens,” said party leader Gerry Adams in an online statement Wednesday.

“This case warrants an immediate full public inquiry into the neglect and maltreatment which caused the deaths of these children.

“Unfortunately, this case is really just the tip of the iceberg in terms of the treatment of women and children in mother and baby homes.”

Colm Keaveney, a Fianna Fail lawmaker in Galway East, insisted that Ireland’s Prime Minister – or Taoiseach – Enda Kenny, must take a lead in investigating the reports.

“These shocking revelations about the appalling treatment of hundreds of babies and their mothers must be dealt with by the highest levels in Government,” he said.

“We need to hear from the Taoiseach today about the Government’s plans to investigate the circumstances surrounding the death of these children, the dumping of their remains, the treatment of their mothers and the State’s role in the activities at this home.”

Archbishop: Huge emotional wrench

A petition set up Tuesday on the activist website Avaaz.org calls for a judicial investigation into the circumstances of the children’s deaths. More than 8,000 people had signed it as of Thursday morning.

The petition, which is addressed to the Irish Minister for Justice and Equality, says, “We are concerned that evidence suggests that the mortality rate for these children was significantly higher than the national rate of infant mortality at the time.

“And we are shocked at reliable, contemporaneous accounts that the children were malnourished and seemingly uncared-for, when the Irish State was paying the Bon Secours to look after them.”

Archbishop Michael Neary, who heads the Tuam archdiocese, welcomed the government’s move to examine what happened at the home – and said it was hard to fathom the suffering of the mothers involved.

“I was greatly shocked, as we all were, to learn of the extent of the numbers of children buried in the graveyard in Tuam,” he said in a statement. “I can only begin to imagine the huge emotional wrench which the mothers suffered in giving up their babies for adoption or by witnessing their death.”

Despite the length of time elapsed, “this is a matter of great public concern which ought to be acted upon urgently,” Neary said.

“It will be a priority for me, in cooperation with the families of the deceased, to seek to obtain a dignified re-interment of the remains of the children in consecrated ground in Tuam.”

He said the Church would work with the Bon Secours Sisters and the local community to put up a memorial plaque to the infants who died.

Neary said that the diocese has no documents related to the home, since it was not involved in running it, while the Sisters of Bon Secours handed over their archives to local authorities in 1961.

He added, “There exists a clear moral imperative on the Bon Secours Sisters in this case to act upon their responsibilities in the interests of the common good.”

Harsh treatment

The Tuam case is the latest high-profile episode in which the state and Catholic Church have been called to account over care of the most vulnerable in Irish society.

A government report last year into the so-called Magdalen Laundries, run by various Catholic orders, acknowledged that Ireland’s government sent thousands of women and girls to “harsh and physically demanding” workhouses, where they worked and lived without pay, sometimes for years. The laundries operated from 1922 to 1996.

While some were sent there by courts, others were unmarried mothers, victims of sexual abuse, orphans considered a burden to relatives or the state, or were mentally or physically disabled.

And earlier this year, Philomena Lee – whose decades-long search for the son she was forced to give up for adoption in the 1950s was the subject of an Oscar-nominated film – launched the Philomena Project in hopes of compelling the governments of Ireland and the United States to open access to adoption records.